Marie Z. Chino

1907-1982

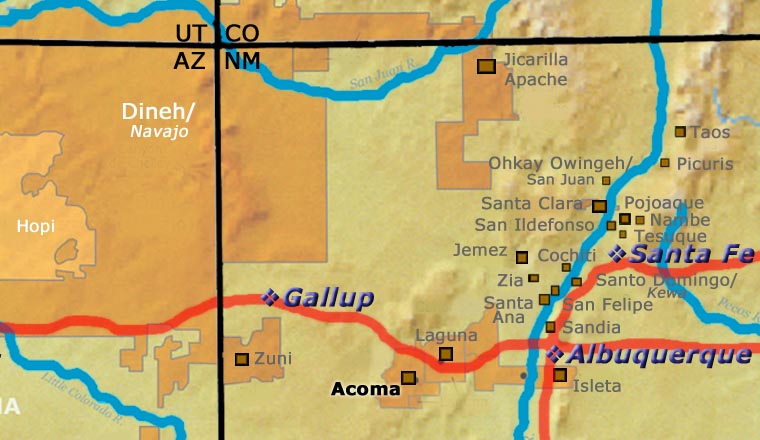

Acoma

Marie Zieu Chino, Lucy M. Lewis and Jessie Garcia are recognized as having been the three most important Acoma potters during the 1950s. The inspiration for their designs came from old potsherds they had gathered to crush for temper in their clay mixtures. Together, the three women led the revival of ancient pottery forms and designs, including the Mimbres, Tularosa and other ancient cultures from around the Acoma region in central New Mexico.

Marie became most known for her amazingly uniform hand-coiled pottery. Her pots were also distinctive for their complex geometric designs as well as the combination of life forms and abstract symbols. Some of her favorite designs included animals, spirals, kiva steps, parrots, rainbows, berries, leaves, rain, clouds, lightning and fine-line snowflakes.

As head of the Chino family, Marie mentored her own family and many others in the finer aspects of the ancient art of pottery making. Her children and grandchildren are numerous and include daughters Grace Chino, Rose Marie Chino and Carrie Charlie Chino.

Marie Z. Chino's pottery can be found in the book, "14 Families in Pueblo Pottery" along with numerous other publications. In 1922, Marie earned her first award at the Santa Fe Indian Market. She was only fifteen. She didn't participate in Indian Market again for years, then went on to receive numerous awards there between 1970 and 1982. In 1998 the Southwestern Association for Indian Arts recognized Marie with a “Lifetime Achievement Award”.

Photo of Marie Z. Chino above is courtesy of Lynne Spivey.

100 West San Francisco Street, Santa Fe, New Mexico 87501

(505) 986-1234 - www.andreafisherpottery.com - All Rights Reserved

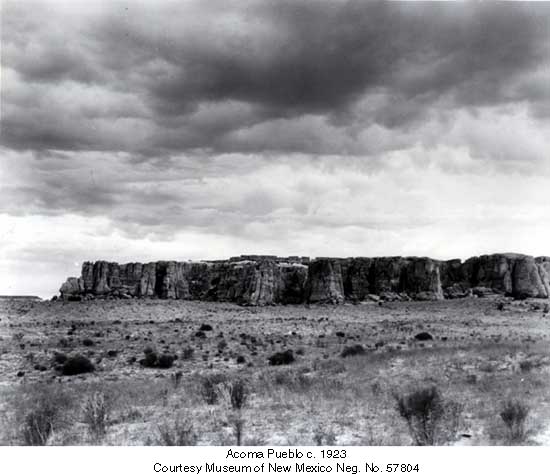

Acoma Pueblo

Sky City

According to Acoma oral history, the sacred twins led their ancestors to "Aaku," a magical mesa composed mostly of white rock, and instructed those ancestors to make that mesa their home. Acoma Pueblo is called "Sky City" because of its position atop the mesa. Acoma is located about 60 miles west of Albuquerque.

According to some archaeologists, a large group of Keres-speaking people left the Chaco Canyon area in the late 900s. They headed south, around the west side of the Mount Taylor volcano and across the Rio San Jose to Aaku, where they merged into a pueblo of people already living there.

Acoma, Old Oraibi (at Hopi) and Taos all lay claim to being the oldest continuously inhabited community in the U.S. Those competing claims are hard to settle as each village can point to archaeological remnants close by to substantiate each village's claim. While the people of Acoma have an oral tradition that says they've been living in the same area for more than 2,000 years, some archaeologists feel more that the present pueblo was established near the end of the major migrations of the 1200s and 1300s. The location is essentially on the boundary between the Mimbres-Mogollon to the south and west, and Ancestral Puebloan cultures to the north and east. Each of those cultures has had an impact on the styles and designs of Acoma pottery, especially since modern potters have been getting the inspiration for many of their designs from ancient potsherds they have found while walking on pueblo lands.

Francisco Vasquez de Coronado ascended the cliff to visit the Acomas in 1540. He afterward wrote that he "repented having gone up to the place." But the Spanish came back again, and kept coming back. In 1598 relations between the Spanish and the Acomas took a really bad turn with the arrival of Don Juan de Oñaté and the soldiers, settlers and Franciscan monks that accompanied him. After ascending to the mesa top, Oñaté decided to force the Acomas to swear loyalty to the King of Spain and to the Pope. When the Acomas realized what the Spanish meant by that, a group of Acoma warriors attacked a group of Spanish soldiers and killed 11 of them, including one of Oñaté's nephews.

Don Juan de Oñaté retaliated by attacking the pueblo, burning most of it and killing more than 600 people. Another 500 people were imprisoned by the Spanish: males between the ages of 12 and 25 were sold into slavery and 24 men over the age of 25 had their right foot amputated. Many of the women over the age of 12 were also forced into slavery and were eventually parceled out among Catholic convents in Mexico City. Two Hopi men also captured at Acoma had one hand cut off. Then they were released and sent home to spread the word about Spain's resolve to subjugate the inhabitants of Nuevo Mexico.

When word of the massacre and the punishments meted out got back to King Philip in Spain, he banished Don Juan de Oñaté from Nuevo Mexico. Some Acomas had escaped that fateful Spanish attack and returned to the mesa top in 1599 to begin rebuilding. In 1620 a Royal Decree was issued establishing civil offices in each pueblo, and Acoma had its first governor appointed. Those governors met at Santo Domingo Pueblo at the All Pueblos Council, the first democratic institution in the Americas, an institution that is still functioning.

By 1680, the situation between the pueblos and the Spanish had deteriorated to the point where the Acomas were extremely willing participants in the 1680 Pueblo Revolt. After the successful Pueblo Revolt, the Spanish retreated to Mexico. Refugees from other pueblos began arriving at Acoma, fearing an eventual Spanish return and reprisals. That strained the resources of Acoma until the Spanish actually did return. Then residents of the pueblo had to make a difficult decision. Many of the refugees chose to try a peaceful solution: they relocated to the ancient Laguna area and made peace with the Spanish as soon as they appeared in the region. Acoma made peace with the Spanish soon after.

Over the next 200 years, Acoma suffered from outbreaks of smallpox and other European-introduced diseases to which they had no natural immunity. They also sided with the Spanish against raiders from the Navajo and Apache tribes. Then New Mexico changed hands a couple times, the railroads arrived and, like every other Native American pueblo, the Acoma people became dependent on inexpensive goods brought in from the outside world.

For many years the villagers were content on the mesa top and they kept advances in technology below. Now most live in villages on the valley floor where water, electricity, natural gas and other "luxuries" are easily available. While a few families still make their permanent home on the mesa top, the old pueblo is used almost exclusively for ceremonies and celebrations these days.

Historically, Acoma was known for large, thin-walled "ollas," jars used for storing food and water. With the arrival of the railroad and tourists in the 1880s, Acoma potters adapted the size, shapes and styles of their pots in order to appeal to the new buyers.

Up into the mid-1960s, most Acoma potters felt it was an inappropriate display of ego to sign their pots. Then Kenneth Chapman convinced Lucy Lewis, Jessie Garcia and Marie Z. Chino of the value of their signatures and they started signing their pieces. The 1960s is also a time when the primary Acoma white clay vein passed through a layer of widely distributed impurities, impurities that passed through the clay filtering process and showed up only during and after the firing. The problem was so bad it affected virtually every Acoma potter and every pot they made. Thankfully, by the late 1960s they had burrowed through that layer of clay and into a deeper layer that didn't have the problem.

100 West San Francisco Street, Santa Fe, New Mexico 87501

(505) 986-1234 - www.andreafisherpottery.com - All Rights Reserved

Chino Family Tree

Disclaimer: This "family tree" is a best effort on our part to determine who the potters are in this family and arrange them in a generational order. The general information available is questionable so we have tried to show each of these diagrams to living members of each family to get their input and approval, too. This diagram is subject to change should we get better info.

-

Marie Zieu Chino (1907-1982)

- Carrie Chino Charlie (1925-2012)

- JoAnn Chino Garcia (1961-) & Lawrence Garcia

- Corinne Louis (1959-)

- Rose Chino Garcia (1928-2000)

- Tena Garcia (1964-)

- Grace Chino (1929-1994)

- Gloria Chino (1955-)

- Carol Chino (1971-)

- Vera Chino Ely (1943-)

- Gilbert Chino (1946-1999)

- Marie's other students:

- Emmalita Chino (daughter-in-law) (1931-) & Patrick Chino

- Brenda Charlie

- Monica C. Chino

- Emmalita Chino (daughter-in-law) (1931-) & Patrick Chino

-

Helen Zieu White (Marie Z. Chino's sister) & Jose Patricio

- Patrick Patricio (1942-) & Doris Concho Patricio (1944-2019)

- Doug Patricio

- Israel Patricio

- Myron Patricio

- Robert Patricio (1976-) & Melanie Patricio

- Felisha Patricio (1997-)

- Kylie Patricio (1999-)

- Juanita Patricio (2001-)

- TobieMae Patricio (2005-)

- Stephanie M. Patricio (1970- ) & Curtis Nez

- Frances (Patricio) Concho (1947-) & Isidore Concho

- Marietta Juanico

- Norbert Patricio

Some of the above info is drawn from Southern Pueblo Pottery, 2000 Artist Biographies, by Gregory Schaaf, © 2002, Center for Indigenous Arts & Studies. Other info is derived from personal contacts with family members and through interminable searches of the Internet and cross-examination of the data found.

(505) 986-1234 - www.andreafisherpottery.com - All Rights Reserved