Lorraine Williams-Yazzie

1955-2024

Dineh (Navajo)

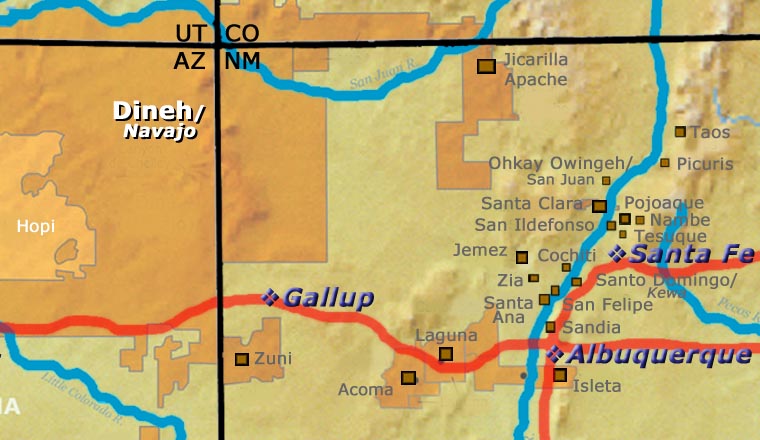

Lorraine Williams-Yazzie was born to Donald and Lillie Yazzie on the Navajo Nation in November 1955. She grew up in the Sweetwater, Arizona area, near Kayenta and Teec Nos Pas. Her father was a traditional Dineh medicine man and her mother was a traditional Dineh herbalist. She was not raised in close proximity to any tradition of pottery making: she began working with clay as an adult.

She married George Williams, the son of Rose Williams, the Matriarch of Dineh pottery. At that time Lorraine was adept at beadwork, sand paintings and weaving but "I didn't know how to draw," she once said. "And you don't want to compete with your in-laws. Rose didn't draw at all, so I decided to try drawing on the clay. By mistake I made a hole in one pot so I went ahead and cut it out. Now I make cutouts regularly."

Lorraine suffered with epilepsy all her life. "Everyone around me thought I had a taboo. No one believed that I really had epilepsy… I found that working with clay kept it away."

She decorated her pottery with a combination of commercially made and natural pigments. She fired each pot outside, separately and upside down, for about three hours with a lot of wood for a very hot burn. Dineh pots are historically coated with hot pine pitch after the firing to give a shiny, more impervious finish.

Lorraine told us that Dineh pottery was historically made only for functional and ceremonial use and for trading purposes. Pottery was not made for sale on the Navajo Nation until the 1980s when galleries and traders came looking for it.

She was featured in Susan Peterson's book Pottery by American Indian Women - The Legacy of Generations. As a result of this book, an exhibit showcasing pottery by these famous women, which included works by Lorraine, toured leading museums across the United States. She was also invited to the National Museum of the American Indian at the Smithsonian Institute in Washington, D.C. to demonstrate traditional Dineh pottery making.

Lorraine participated in shows at the Heard Museum in Phoenix, Tucson Museum of Art, the Museum of Northern Arizona in Flagstaff and the Santa Fe Indian Market. She earned Best in Show ribbons at the Heard Museum and at the Museum of Northern Arizona. She earned First and Second Prize ribbons at Santa Fe Indian Market, the Heard Museum and the Tucson Museum of Art. Her favorite shapes were tall neck vases and wedding vases, her favorite designs were based on Dineh carpet designs. She told us she got her inspiration from her mother-in-law, her granddaughter (Raven Roy) and the everyday life that surrounds her.

She sometimes signed her work: "Lorraine Yazzie." Sometimes she signed with an LWY logo and other times she used "LWY-Rain."

100 West San Francisco Street, Santa Fe, New Mexico 87501

(505) 986-1234 - www.andreafisherpottery.com - All Rights Reserved

Dineh

A view in Monument Valley

The Dineh refers to themselves as "Dineh" because the word means "the People" in their language. "Navajo" is a name that was given to them by the early Spanish. Historical and archaeological evidence points to the Dineh people entering the Southwest around 1400 CE. Their oral history still contains stories of that migration as the journey began in eastern Alaska and northwestern Canada centuries after their ancestors made the journey across the Bering Land Bridge from central Asia about 10,000 years ago. They were primarily hunter-gatherers until they came into contact with the Pueblo peoples and learned the basics of survival in this drier climate. Dineh oral history points to a long relationship between the Dineh and the Puebloans as they learned from and traded with each other.

When the Spanish first arrived, the Dineh occupied much of the area between the San Francisco Peaks (in Arizona), Hesperus Mountain and Blanca Peak (in Colorado) and Mount Taylor (in New Mexico). Spanish records indicate they traded bison meat, hides and stone to the Puebloans in exchange for maize and woven cotton goods. It was the Spanish who brought sheep to the New World and the Dineh took to sheep-herding quickly with sheep becoming a form of currency and sign of wealth.

When the Americans arrived in 1846, things began to change. The first fifteen years were marked by broken treaties and increasing raids and animosities on both sides. Finally, Brigadier General James H. Carleton ordered Colonel Kit Carson to round up the Dineh and transport them to Bosque Redondo in eastern New Mexico for internment. Carson succeeded only by engaging in a scorched earth campaign in which his troops swept through Dineh country killing anyone carrying a weapon and destroying any crops, livestock and dwellings they found. Facing starvation and death, the last band of Dineh surrendered at Canyon de Chelly.

Carson's campaign then led straight into "the Long Walk" to Bosque Redondo, a 300-mile trek during which at least 10% of the people died along the way. At Bosque Redondo they discovered the government had not allocated an adequate supply of water, livestock, provisions or firewood to support the 4,000-5,000 people interned there. The Army also did little to protect them from raids by other tribes or by Anglo citizens. The failure was such that the Federal government and the Dineh negotiated a treaty that allowed the people to return to a reservation that was only a shadow of their former territory little more than a couple years after they had left. However, succeeding years have seen additions to the reservation until today it is the largest Native American Reservation in the 48 contiguous states.

Large deposits of uranium were discovered on the Navajo Nation after World War II but the mining that followed ignored basic environmental protection for the workers, waterways and land. The Dineh have made claims of high rates of cancer and lung disease from the environmental contamination but the Federal government has yet to offer comprehensive compensation.

As a semi-nomadic tribe, the Dineh never made much pottery, preferring to use baskets for most storage purposes. They did produce a small amount of pottery for ceremonial uses. Once they were settled on a reservation, pottery began to make more sense. From a beginning making simple wares for colonial estates they transformed their pottery into art. After 1950 Cow Springs brownware began to appear on the market. A trader named Bill Beaver was in Shonto back then, encouraging local potters to "make something different" and the market in the outside world responded positively to those different creations.

Rose Williams is considered the matriarch of modern Dineh pottery. She learned from Grace Barlow (her aunt) and passed her knowledge and experience on to her daughters and many others. Today, most Dineh pottery is heavy, thick-walled and coated with pine pitch (a sealer they also use on many of their baskets). Most Dineh pottery has little in the way of decoration but many pieces have a biyo' (a traditional decorative fillet) around the rim. Unlike Puebloan potters, Dineh potters do not grind up old pot sherds and use them for temper in creating new pottery. Their religion says those pot sherds are infused with the spirits of their ancestors and that forbids the reuse of the material. Similarly, Dineh religion limits Dineh potters to using primarily Dineh carpet designs in the decoration of their pots.

Dineh potters have also created a panoply of folk art, including unfired clay creations called "mud toys." Other Dineh potters, like Christine McHorse, have graduated into the mainstream of American Ceramic Art and easily compete among the finest ceramic artists on Earth.

100 West San Francisco Street, Santa Fe, New Mexico 87501

(505) 986-1234 - www.andreafisherpottery.com - All Rights Reserved