Kimo DeCora

Isleta/Winnebago

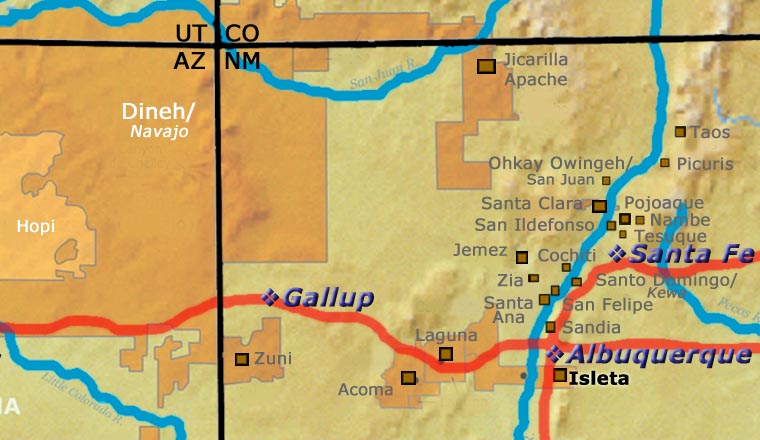

Born in 1951 to Rev. Wilbur J. DeCora and Lupita M. Jojola, Isleta Pueblo potter Kimo DeCora is half Isleta, half Winnebago. He learned the basics of traditional pottery making on his own but he also learned through watching Cipriano Romero Medina and John Montoya at work.

Kimo's favorite shapes to make are bowls, jars, small owls and his trademark miniatures. Over the years his pieces have earned him 18 blue ribbons at the Winnebago, NE Fine Arts Show, 6 more blue ribbons at the Albuquerque CeramicFest and several blue ribbons at Andrea Fisher Fine Pottery.

His inspiration comes from his pre-Columbian ancestors, and it's their designs he most often uses to decorate his work. His signature reflects his tribal affiliation (W/T: Winnebago Ho-Chunk / Isleta-Tiwa) and some subconscious doodling.

"I'm not the extrovert type and, like many others, don't need to be noticed to be happy ('Call me Hieronymous, cuz I like being anonymous'). It's a blessing to enjoy good health and be appreciated for the medium I express myself with. I also believe humor is a good thing."

100 West San Francisco Street, Santa Fe, New Mexico 87501

(505) 986-1234 - www.andreafisherpottery.com - All Rights Reserved

Isleta Pueblo

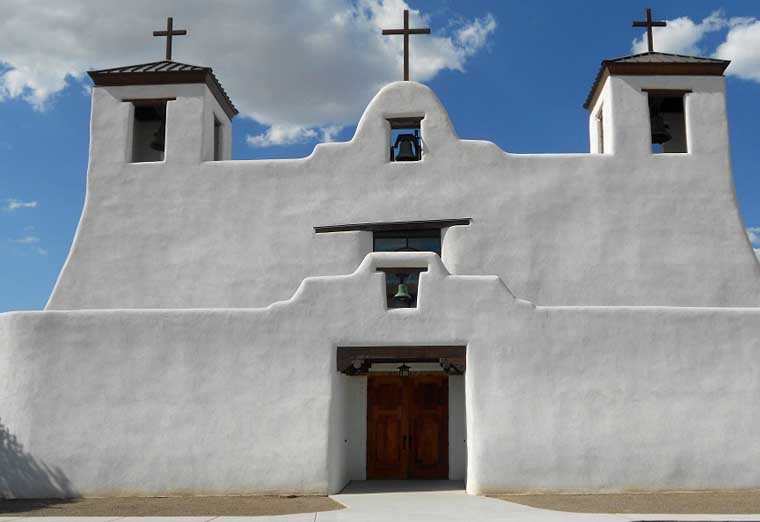

San Agustin de la Isletas Mission

Isleta Pueblo is said to have been founded in the 1300s. Archaeologists have put forth various ideas as to where the people came from with some scholars saying they migrated north from Mogollon/Mimbres settlements to the south while others say they migrated southeastward from either Chaco Canyon in the 1100s and 1200s or from the Four Corners area in the 1200s and 1300s. Their Tiwa language is shared with nearby Sandia Pueblo and a very similar tongue is spoken to the north at Taos and Picuris Pueblos. The two dialects are sometimes referred to as Southern and Northern Tiwa.

In 1540, when Coronado passed by, there were 15 major and minor Tiwa pueblos in the Middle Rio Grande area, and he seems to have attacked every one of them, looking for food and gold. By 1598, when Don Juan de Oñaté came north to conquer and occupy Nuevo Mexico, he found only Isleta and Alameda (Sandia) left. The others had all succumbed to European diseases introduced to them 60 years before, diseases they had no immunity to.

When the Franciscan priests arrived in the area (with de Oñatéin 1598 CE) they named the pueblo "Isleta" (meaning: island). The residents were relatively accommodating to the Spanish priests when compared to the reception the same priests got in other areas of Nuevo Mexico (making Isleta something of an "island of safety" for the Spanish in an ocean of hostility). When the Pueblo Revolt of 1680 happened, Isleta either couldn't or wouldn't participate in the rebellion. When the Spanish governor left Santa Fe he went to Albuquerque first, then to Isleta, and gathered his priests and troops. None wanted to go back north to fight so when they left and headed south, many Isletans went south to the El Paso area with them. Others fled to the Hopi settlements in Arizona and returned after the fighting was clearly over, many with Hopi spouses. When the Spanish returned in 1682 they found the Isleta mission church burned and the main structure was being used as a livestock pen. When the Spanish returned in force in 1692 they found Isleta completely empty and burned. The governor ordered the pueblo be rebuilt and resettled so residents were brought in from Taos and Picuris to the north and from Ysleta del Sur to the south, near El Paso. By 1720 a new, grander mission had been rebuilt on the foundations of the first.

Over the next century dissident members of the Laguna and Acoma Pueblo communities migrated to Isleta. While they were welcomed into the main Isleta pueblo at first, friction developed over the years until in the late 1800s, the small communities of Oraibi and Chicale were established. Most of the newcomers moved to one or the other.

The advent of the railroad in New Mexico was almost the end of the Isleta community as so many of the men went to work for the railroad. While the remaining residents managed to hold on to some of their social and religious practices, other elements of their culture almost disappeared, pottery making being one of those traditions that barely survived.

Today, making pottery the traditional way is practiced by only a few potters and their close family members.

100 West San Francisco Street, Santa Fe, New Mexico 87501

(505) 986-1234 - www.andreafisherpottery.com - All Rights Reserved