Karen Abeita

Hopi

"Here I was surrounded by rows and rows of shelves loaded with pottery from Sikyátki. I took out my sketch book and a pencil, quickly sat down and began copying designs. I applied to the biggest Indian art show in North America, the Santa Fe Indian Market, and was selected as one of the upcoming new artists from among several hundred applicants. I knew in my mind that there was no turning back." - Karen speaking of time she spent at the Philadelphia Museum of Art

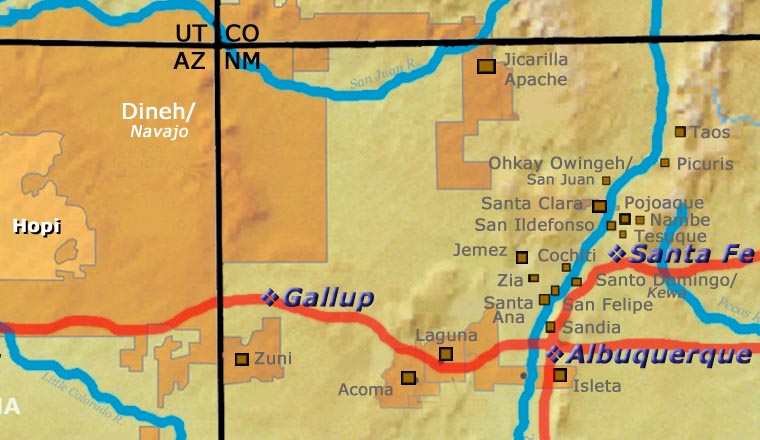

In 1960, Karen Abeita was born in an Albuquerque hospital to a Hopi-Tewa woman named Lenora Nahoodyce Abeyta. Lenora had married an Isleta Pueblo man named Isidor Abeita, Sr. and moved from Hopi to Isleta Pueblo (which move was counter to tradition) but she returned to Hopi after Karen's birth, and Karen grew up in a traditional Hopi-Tewa home, a member of the Kachina/Parrot clan. She still lives a very strong traditional life where she speaks her native tongue and actively participates in tribal dances and ceremonies.

Karen says she has been a potter since she could first reach her hands into the clay bucket. Her grandmother, Mamie Nahoodyce, and her great-aunt, Patty Maho, and great-grandmothers, Po'Tsah-Weh, Pong Sayah, Kweh-Kah and several other aunts: Joy Navasie, Beth Sakeva and Sadie Adams, were all well respected potters.

Karen, however, credits her childhood friend, Fawn Navasie, with being her primary teacher. With her expertise and patience, Fawn taught Karen how to mold large pots, how to fire using sheep manure and, most of all, how to respect the clay and never forget to pray. She also believes that putting your heart and mind into what you are creating is the ultimate reward in the end because in front of your eyes is something you've created.

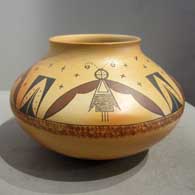

Karen says she thanks the clay for letting her be who she is. Her pottery is all hand coiled. The only tool she uses is a piece of gourd to shape her pots. Her pots range from 3 inches by 2 inches to almost 24 inches in diameter and 18 inches in height.

Her painting is done with brushes made from yucca leaves and the paint is made from the mustard seed plant. The boiled-down paint is poured onto a painting stone and rubbed back and forth to mix with black hematite. The painting is one of the most important procedures. An artist can paint the most beautiful design on pottery but if the paint wasn't mixed properly, it will all rub off.

After the painting is complete, the pottery is then fired outside with sheep manure. This can take up to 6 hours so patience is key. Cooling off too quickly or uncovering too soon will result in the pottery cracking. Karen prefers to allow the pots to cool slowly, taking most of a day, unless she does the firing in the evening and uncovers the pots the next morning.

The designs Karen paints on her pottery are usually near-duplicates of designs she's found on potsherds from the ancient village of Sikyátki. Today, Sikyátki is barely mounds of stone and dirt where the ground is littered with thousands of broken potsherds. To Karen, the ancient village is a gold mine. She says she has never seen duplicates of the same design. She also says she loves to stand on the highest point in the ruin and let her imagination free to take her back in time to when the village was alive. "What did a potter feel like when she was uncovering her just-fired pot? Was she excited? Did everyone in the village come to see the latest masterpiece?"

Karen says when she makes her journey to the ruins, she prays, then walks around and draws whatever designs she sees among the broken sherds. After filling several pages with designs, she goes home and begins to paint what she calls "a sherd pot."

A sherd pot can consist of hundreds of designs, none of them ever the same size, shape or style. It is also very time consuming to paint: a small sherd pot can take eight days from sun up to sun down to finish painting. It is a style she has worked long and hard to create and it still continues to evolve as she finds new potsherds with new designs.

Her pottery has taken her to many places. By invitation, Karen went to see the large collection of Sikyátki pottery in the vaults of the Philadelphia Museum of Art. Previously she had seen complete Sikyátki pots only in pictures so seeing actual pots that had been made and used about two miles from her home back in the early 1300s was like a direct connection from the past to the present.

All the hard work and long hours were about to pay off. She soon proved to herself and the world that she, too, is an excellent traditional potter. Since then Karen has participated in more than 20 Santa Fe Indian Markets and has won numerous awards, including the prestigious Helen Naha Memorial Award. She has also won a First Place ribbon for Traditional Pottery at the Eiteljorg Museum in Indianapolis.

Knowing that only the very best win the Helen Naha award and are counted in the company of award-winning Hopi-Tewa potters like Rondina Huma, Steve Lucas, Mark Tahbo, Rainy Naha and Dianna Tahbo, Karen feels that she has achieved a major goal in her life. Another goal she set for herself is to put all the designs she has collected from the ruins of Sikyátki in a book.

Some Awards Karen has Won

- 2020 Heard Museum Guild Indian Fair & Market, Classification II - Pottery, Division A - Painted, native clay, hand built, fired out-of-doors: Second Place. Awarded for artwork: "For the Love of Dragon Flies"

- 2018 Santa Fe Indian Market. Helen Naha Memorial Award. Southwestern Association for Indian Arts

- 2017 Santa Fe Indian Market, Classification II - Pottery, Division B - Traditional, Category 601 - Painted polychrome pottery in the style of Hopi, any form: Second Place

- 2016 Heard Museum Guild Indian Fair & Market, Classification II - Pottery, Division A - Traditional, native clay, hand built, painted: Second Place

- 2015 Heard Museum Guild Indian Fair & Market, Classification II - Pottery, Division A - Traditional, native clay, hand built, painted: First Place

- 2010 Santa Fe Indian Market, Classification II - Pottery, Division B, Category 501 - Painted polychrome in the style of Hopi, any form: First Place

- 2002 Heard Museum Guild Indian Fair & Market, Classification VIII - Pottery, Division A - Traditional: Best of Division. Awarded for artwork: "Shards, Shards, Shards"

- 2001 Santa Fe Indian Market, Classification II - Pottery, Division F - Traditional pottery, Category 1302 - Other bowl forms: Third Place

- 2001 Santa Fe Indian Market, Classification II - Pottery, Division E - Traditional pottery, jars painted designs on matte or semi matte surface, Category 1201 - Jars, Hopi: Third Place

- 2000 Santa Fe Indian Market, Classification II - Pottery, Division J - Pottery Miniatures, 3" or less in height or diameter, Category 1605 - Traditional forms, other bowls: Third Place

- 2000 Santa Fe Indian Market, Classification II - Pottery, Division E - Traditional pottery, jars painted designs on matte or semi matte surface, Category 1201 - Jars, Hopi (up to 6" tall): Third Place

- 2000 Santa Fe Indian Market, Classification II - Pottery, Division F - Traditional pottery, Category 1302 - Seed bowls (over 7" in diameter): Third Place

- 1999 Santa Fe Indian Market, Classification II - Pottery, Division E - Traditional pottery, jars, painted designs on matte or semi-matte surface, Category 1201 - Jars, Hopi (up to 6" tall): Second Place

- 1999 Santa Fe Indian Market, Classification II - Pottery, Division F - Traditional pottery, painted designs on matte or semi-matte surface, all forms except jars (in the style of Hopi), Category 1301 - Seed bowls (up to 7" in diameter): First Place

- 1999 Santa Fe Indian Market, Classification II - Pottery, Division F - Traditional pottery, painted designs on matte or semi-matte surface, all forms except jars (in the style of Hopi), Category 1302 - Seed bowls (over 7" in diameter): Second Place

- 1998 Santa Fe Indian Market. Pottery, Classification II - pottery, Division E - traditional pottery, jars..., Category 1201 - Hopi (up to 6" tall): Third Place

- Division J - Pottery Miniature, Category 1604 - traditional forms, seed bowls, other than black: First Place

- Classification II-Pottery. Division E - traditional pottery..., Category 1201 - Jars, Hopi: Third Place

- Division F - traditional pottery..., Category 1301 - Seed bowls: Third Place - 1997 Santa Fe Indian Market. Classification II - Pottery, Division I - Traditional..., Category 1301 - Seed bowls: First Place

- 1995 Santa Fe Indian Market. Hopi Jars: First Place

- Bowls over 6 inches: Second Place - 1995 Lawrence Indian Arts Show, Lawrence, KS. 3 dimensional (large Hopi jar): Best of Show

- 1994 Santa Fe Indian Market. Category - Hopi Jars over 9 inches tall: First Place

- 1994 Gallup InterTribal Ceremonial. Category - Hopi Jars: First Place

- 1994 New Mexico State Fair. Category-Hopi Jars: Second Place

- 1993 Santa Fe Indian Market. Santa Fe, NM. Category 1443 Misc. Jars and Vases: First Place

- Hopi vases: First Place

- Cat., Seed Jar: Honorable Mention - 1992 Santa Fe Indian Market. Category 1401-Seed bowls. Second Place

100 West San Francisco Street, Santa Fe, New Mexico 87501

(505) 986-1234 - www.andreafisherpottery.com - All Rights Reserved

The Hopi People

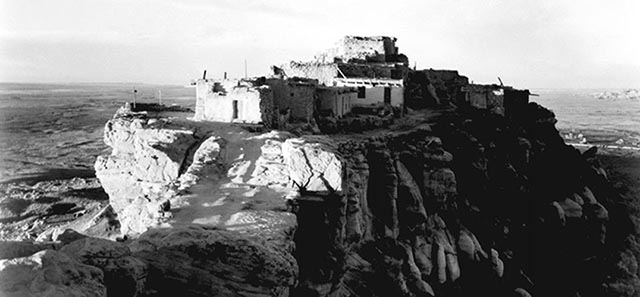

Walpi, as seen by Ansel Adams in 1941

The Hopi People and Their Pottery

Looking across Tewa Village to First Mesa

Pottery was being made in the area of the Hopi mesas before generational migrants from the area of central Mexico began to arrive in the 600's. Those migrants brought a much better ceramic technology with them. They also brought a whole new design vocabulary, architectural advancements, more defined rituals and better seeds, along with other agricultural advancements. They spread out across the Southwest between the Colorado River and the Rio Grande, from the Chihuahua and Sonora deserts north to the Great Salt Lake, and they multiplied. The weather of this countryside was very fickle, though, and they had to discover new ways to store their food and keep it good for years. The best tool for preserving things was pottery. Then they began decorating their pottery with their prayers for the seed within, and for the survival of their people.

For hundreds of years those designs were repetitive geometrics, in black-on-white or black-on-gray-white bisques, most matte but more and more polished as time went on. In the 900's, from the south again, figures in black-on-white were introduced. Then came figures and designs in red-and-black-on-white. Then came figures and designs in various combinations of red, black and white on various backgrounds. Each step in the development of decorative and color schemes is reflective of experiential religious developments within one clan or another, one pueblo or another. A lot of what flowered into what we know now as "Sikyátki style and design" was developed in bits and pieces along the rim of Antelope Mesa. It took the experience of Sikyátki to put it all together. Just as the design palette of Sikyátki reached its peak, the village's chief determined they had strayed too far from the traditionally conservative Hopi path and they needed to be put to death for it. He arranged with the elders of Walpi and other villages to have the deed done and sometime in 1625 it was completed. Everyone in the village was killed except for a few ritual specialists who were saved for their spiritual value.

A mural from Awatovi

The styles and designs of Sikyátki lived on on some Awatovi pottery for a few years but the entire design palette changed after the Spanish arrived in force in 1629. San Bernardo Polychrome came into production almost immediately with the reduction in labor force as so many of the Awatovis were forced to serve the priests and build a mission. The design palette changed, too, when all the kachina designs were forced out by the Franciscan priests. Almost everything changed again with the Pueblo Revolt of 1680. There was a general return to themes prevalent before the Spanish arrived across the entire Southwest, except by then most potters were firing their pots using sheep, cow or horse manure. Around the Hopi mesas, a merging of designs and supernaturals with the layouts from the San Bernardo and Sikyatki phases happened. Some archaeologists have termed the pottery that was produced for 100 years after the Pueblo Revolt as "Payupki phase." It faded out around 1780, about the same time the last of the Tiwas and Keresans returned to the Rio Grande Valley from the village of Payupki on Second Mesa. After that came the phases of Polacca Polychrome, including the white-slipped years after the times of drought and disease in the 1800s that were spent at Zuni.

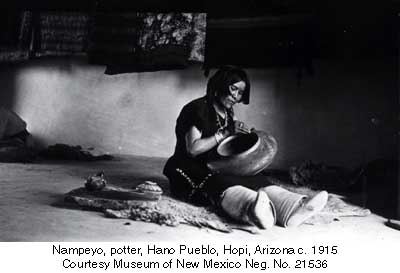

By the mid-1800s, the Hopi pottery tradition had been almost completely abandoned, its utilitarian purposes taken over by cheap enamelware brought in by Anglo traders. Hopi pottery production sputtered along until the 1880's when one woman, Nampeyo of Hano, almost single-handedly revived it. Nampeyo lived in Hano on First Mesa and was inspired by pot sherds found among the nearby ruins of the ancient village of Sikyátki. Like every other potter around First Mesa at the time, Nampeyo was producing jars, bowls and canteens, often with one surface slipped white and decorated with designs in black-and/or-red. At the urging of Anglo traders' Alexander Stephen and Thomas Varker Keam, she began experimenting with polishing the surface of pieces coiled entirely of Jeddito yellow clay and then painting her designs directly on that. Today, credit is given to Nampeyo for fully reviving the Sikyátki style. She was so good that Jesse Walter Fewkes, the first archaeologist to formally excavate Sikyátki, was concerned that her creations would shortly become confused with those made hundreds of years previously.

Sikyátki pottery shapes are very distinctive: flattened jars with wide shoulders; low, open serving bowls decorated inside; seed jars with small openings and flat tops; painting methods of splattering and stippling and very distinctive designs. The Sikyátki style seems to have evolved as various Zuni-, Keres- and Towa-speaking potters came together with Water Clan potters from the Hohokam areas of southern Arizona and northern Mexico, and they began working with clays found in the nearby Jeddito valley area. Over the years, other clans came to the area and made their own contributions to what we now refer to as "Sikyátki Polychrome." According to Jesse Walter Fewkes, that merging of styles, techniques and designs created some of the finest ceramics ever produced in prehistoric North America.

Today's Hopi Pottery

Most Hopi pottery is unmistakable in its shapes, colors and designs. The Hopis are blessed with multiple excellent clay sources, each offering a different deep color after polishing and firing. Most Hopi pottery uses a buff, red, white or yellow clay body. Some kachina carvers make pottery and sometimes carve and etch their surfaces. Most Hopi potters, though, form their pieces and paint their decorations using colors derived from boiled-down plants, watered-down clay and from crushed minerals.

Much of the symbology painted on Hopi pottery is themed with "bird elements:" eagle and parrot tails, feathers, beaks and wings, and with katsinam (images of their gods) and permutations of migration patterns. Many Hopi, Hopi-Tewa and Tewa potters are members of the Corn Clan and their annual religious cycle revolves around the seasons of corn. The vast majority of today's Hopi pottery shapes and the designs painted on them are obvious descendants of the work of potters who existed 200-and-more years ago.

The above paragraph applies mostly to potters from the vicinity of First Mesa. The few potters from Second and Third Mesas seem to derive their design palettes from farther back in time, to the geometric designs, patterns and figures of the rock art prevalent before the advent of the katsinam, and the emergence of the Medicine, Sacred Clown and Warrior societies 800 years ago.

The view south from near Old Oraibi

Other Resources:

100 West San Francisco Street, Santa Fe, New Mexico 87501

(505) 986-1234 - www.andreafisherpottery.com - All Rights Reserved