Joshua Madalena

Jemez

“Joshua Madalena has finally succeeded in replicating the Black-on-White techniques. His painstaking experimentation with clays, paints, and firing techniques has captured the essence of the ancestral pottery. His designs and forms are drawn from the ancient vessels, and his raw materials are true to the landscape of the Jemez Mountains. We are witness to a true revival, both of a technical process and of an essential historical element of Jemez culture.” Dr. Eric Blinman, past Director, Maxwell Museum of Anthropology at the University of New Mexico.

Joshua Madalena was born into Jemez Pueblo in September, 1966, the son of Reyes and José Madalena. He finished high school and enlisted in the US Army for a few years before returning to Jemez. Shortly after his return, he served as a Lieutenant Governor of the pueblo.

His mother and grandmother (Evelyn Vigil) were potters and he'd observed them making pottery as he grew up but he wasn't interested in working with clay yet. It wasn't until after his term as Lieutenant Governor that he really dedicated himself to the working with the Clay Mother.

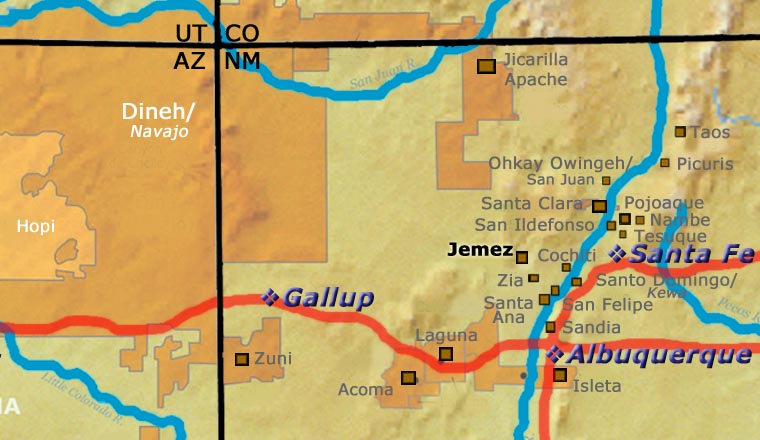

First though, he did a lot of research into the history of the Jemez (Hemish) people and where they originated. Eventually, he followed the trail to the Fremont people of the Great Basin area and a more than 1000-year-long migration push from central Utah to the Jemez Mountains where they are now. Along the way there were stops along the Lower San Juan River, the canyons and valleys west of the the Mesa Verde area, then the Gallina Highlands and, finally, into the Jemez Mountains where their presence has been growing since about 700 CE. That said, they didn't arrive into an unpopulated space. The whole of northern New Mexico had been occupied by Tanoan people for centuries and any incoming migrants generally merged with those communities.

Joshua studied all this as he also made pottery, each pursuit reinforcing the other in his life. These days, his pottery is usually based on the forms and designs of the ancient Jemez people (pre-contact with the Spanish), as their pots and potsherds have been discovered in ancient pithouses, pueblos and fieldhouses across the Jemez Mountains.

Jemez Black-on-white is the traditional pottery of the Hemish, or Jemez People. The pottery is tempered with volcanic tuff, slipped with a white slip, painted with a carbon (vegetable) paint, and pit-fired in a reduction (oxygen free) atmosphere. The Hemish feel they have been established in the Jemez Mountains of New Mexico from time immemorial, building the foundations for the strong and independent Towa communities that were encountered by the Spanish. While under the Spanish rule of Juan de Oñate (1598) to Diego de Vargas (1698), the Jemez Black-on-White pottery tradition was forcibly lost due to Spanish oppression and forced slave labor for the Franciscan priests.

Rediscovering the process by which Jemez Black-on-White was originally made proved quite difficult. Through more than 10 years of laborious trial and error, Joshua was able to successfully replicate his ancestors' works, a Hemish pottery tradition that had been lost for more than 300 years.

Now the clays and slip have been located and the secrets of the painting and firing techniques have been rediscovered. These techniques have been most difficult to recover since there are no modern traditions that maintained the secrets of high temperature organic pit-firing. Every pot is hand coiled and hand painted. The paint, made of plant extracts, soak into the vessel surface before firing. The painted decorations must survive the high temperatures, leaving a design of black carbon trapped within the polished surface of this special white slip. The success of this very complex process depends on controlling the availability of oxygen around the vessel during firing.

In 2012, Joshua was honored with the prestigious Lifetime Achievement Allan Houser Legacy Award and the Maria Poveka Award by the Southwestern Association for Indian Arts (SWAIA) at the Santa Fe Indian Market for his contributions to the Native art world. These awards are the highest honor that SWAIA bestows upon a Native artist. He has also won Best of Show, First Place and Second Place awards, in addition to at least one Curator's Choice Award.

He told us his favorite shapes to make are large ollas and storyteller figures. His designs are based on the ancient patterns found on pot sherds scattered all through the Jemez Mountains. He also said he gets his inspiration when he thinks of the sacrifices his ancestors made to keep his people alive.

When he's not involved with some aspect of making pottery, Joshua says he likes to travel, and to go fishing with his grandchildren. Earlier in life he was a member of the US Army Marching Band and he still volunteers to play the bugle for the services of deceased veterans. He also volunteers and works to provide assistance for needy families at Jemez.

100 West San Francisco Street, Santa Fe, New Mexico 87501

(505) 986-1234 - www.andreafisherpottery.com - All Rights Reserved

Jemez Pueblo

Ruins of San Jose de las Jemez Mission

As the drought in the Four Corners region deepened in the late 1200s, several clans of Towa-speaking people migrated southeastward from the Four Corners area to the Canyon de San Diego area the southern Jemez mountains, in what is now north-central New Mexico. Other clans of Towa-speaking people migrated southwest and settled in the Jeddito Wash area, below Antelope Mesa and southeast of Hopi First Mesa, in what is now northeastern Arizona. The migrations began in earnest in the mid 1200s and were mostly complete by the mid 1300s.

Archaeologist Jesse Walter Fewkes argues that potsherds found in the vicinity of the ruin at Sikyátki (near the foot of Hopi First Mesa) speak to the strong influence of earlier Towa-speaking potters on what became "Sikyátki Polychrome" pottery (Sikyátki was a village at the foot of First Mesa, destroyed before the first Hopi contact with the Spanish in 1540). Fewkes maintained that Sikyátki Polychrome pottery was the finest ceramic ware ever made in prehistoric North America.

Francisco de Coronado and his men arrived in the Jemez Mountains of Nuevo Mexico in 1539. By then the Jemez people had built several large masonry villages among the canyons and on some high ridges in the area. Their population was estimated at about 30,000 and they were among the largest and most powerful tribes in northern New Mexico. Some of their pueblos reached five stories high and contained as many as 3,000 rooms.

Because of the nature of the landscape they inhabited, growing food was very hard. So the Jemez became traders, too, and their people traded goods all over the Southwest and northern Mexico.

The arrival of the Spanish was disastrous for the Jemez and they resisted the Spanish with all their might. That led to many atrocities against the tribe until they rose up in the Pueblo Revolt of 1680 and evicted the Spanish from northern New Mexico. With the Spanish gone, the Jemez destroyed much of what they had built on Jemez land. Then they concentrated on preparing themselves for the eventual return of the hated priests and the Spanish military.

The Spanish returned in 1692 and their efforts to retake northern New Mexico bogged down as the Jemez fought them doggedly for four years. In 1696 many Jemez came together, killed a Franciscan missionary and then fled to join their distant relatives in the Jeddito Wash area. They remained at Jeddito Wash for several years before returning to the Jemez Mountains. As a result of that long ago contact, there are still strong ties between the Jemez and their cousins on Navajo territory at Jeddito. On their return to the Jemez Mountains, the people built the pueblo they now live in (Walatowa: The Place) and made peace with the Spanish authorities.

Some of the Jemez people had been making a type of plainware pottery (simple, undecorated, utilitarian) when they were still in the Four Corners area, while others had developed a distinctive type of black-on-white pottery. In moving to the Jemez Mountains, they brought their knowledge and techniques with them but had to adapt to the different materials available to work with. Over time, the Jemez got better in their agricultural practices and began trading agricultural goods to the people of Zia Pueblo in return for pottery. By the mid-1700s, the Jemez people were producing almost no pottery.

East of what is now Santa Fe is where the ruins of Cicuyé (Pecos) Pueblo are found. Cicuyé was a large pueblo housing up to 2,000 people at its height. The people of Cicuyé, and some in the northern Galisteo Basin, were the only other speakers of the Towa language in New Mexico. When that area fell on increasingly hard times (Apache and Comanche raids, European diseases, drought), Cicuyé was finally abandoned in 1838 when the last 17 residents moved to Jemez. The Governor of Jemez welcomed them and allowed them to retain many of their Cicuyé tribal offices (governorship and all). Descendants of former Cicuyé families still return to the site of their ancestral home every year to perform religious ceremonies in honor of their ancestors.

When general American interest in Puebloan pottery started to take off in the 1960s, the people of Jemez sought to recover that lost heritage. Today, the practice of traditional pottery-making is very much alive and well among the Jemez.

The focus of Jemez pottery today has mostly turned to the making of storytellers, nativities and other figures. Figures are an art form that now accounts for more than three-quarters of their pottery production.

Storytellers are usually grandparent figures with the figures of children attached to their bodies. The grandparents are pictured singing tribal songs and oral histories to their descendants. While this visual representation was first created at Cochiti Pueblo (a site in close geographical proximity to Jemez Pueblo) in the early 1960s by Helen Cordero, it speaks to the relationship between grandparents and grandchildren of every culture. Nativities, corn maidens, singing angels and many different animal forms are also popular among the potters of Jemez.

The pottery vessels made at Jemez Pueblo today are generally not black-on-white. Instead, the potters have adopted many colors, styles and techniques from other pueblos to the point where Jemez potters no longer have one distinct style of their own beyond that which stems naturally from the materials they themselves acquire from their surroundings: it doesn't matter what the shape or design is, the clay itself says uniquely "Jemez."

100 West San Francisco Street, Santa Fe, New Mexico 87501

(505) 986-1234 - www.andreafisherpottery.com - All Rights Reserved