Dawn Antelope

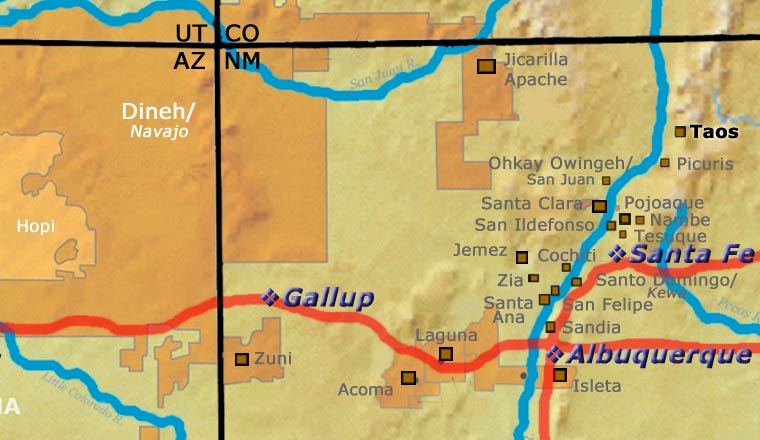

Taos

"If you're absolutely comfortable and at ease with yourself and the world, that will come out in your pottery." - Dawn Antelope

Dawn Antelope was born into Taos Pueblo in 1943. He attended the Pueblo day school, then Taos High School, then Brigham Young University. After graduating from BYU, he was drafted and served two years in the military. After his discharge, he settled in Denver for a couple years, then returned to Taos where he found work as a tutor, public school counselor and aide. His interest in history led him to New Mexico Highlands University where he earned a degree in history and journalism, with a teaching certificate, in 1979. In 1980 he started making pottery.

He says he learned how to make pottery from his mother, Rafaelita Espinoza. As generations of Pueblo women before her had, she made the pots and vessels needed by her family. She also sold some of her wares to visitors at Taos Pueblo.

Dawn Antelope learned to spot the right color, texture and consistency of the local clay that makes the best pottery through scouring the landscape around U.S. Hill, in the forest south of the pueblo. The clay he collects is thick and rich in color, glittering with flakes and chunks of mica.

From June through October, Dawn Antelope collects clay from the nearby hills, hauling it to his home in 26-gallon cans. He needs to collect enough material in the summer to last him through the winter. In his back yard, looking up at Taos Mountain, he begins processing the clay, pulverizing and screening it to remove impurities. The process is hard work, but he says it's therapy, and it's all he wants to do

He rolls the clay between his hands into colls, carefully stacking and pinching them together to form his traditional pots, and his round-bottom cooking pots, hour-glass water jars and wedding vases. For a long time he was the only man at Taos Pueblo who made, and sold, his own pottery. All his work is fired in an horno behind his house. The hive-shaped adobe horno his mother built many years ago is weathered and burnt from years of cottonwood flames. And like her, he doesn't fire on cloudy or windy days, that weather tends to make his pots cloudy and dark.

Traditional potters also use only a few simple tools in their process. Dawn Antelope scrapes the interior of his pots with the broken gourd shell. He uses a smooth butter knife, with his hands and a wet cloth, to shape and smooth the exterior. The forms he makes are simple, with little-or-no decoration, although he sometimes adds appliques of frogs, lizards, bison and ears of corn.

Photo of Dawn Antelope courtesy of Duane Anderson, All That Glitters, 1999.

100 West San Francisco Street, Santa Fe, New Mexico 87501

(505) 986-1234 - www.andreafisherpottery.com - All Rights Reserved

Taos Pueblo

North House, Taos Pueblo

Today's Taos Pueblo consists of two main structures, both of which are counted among the oldest continuously inhabited structures in the United States. The location straddles the Rio Pueblo de Taos (also known as Red Willow Creek), whose headwaters rise in the nearby Sangre de Cristo Mountains. The pueblo was designated a National Historic Landmark in 1960 and was designated a UNESCO World Heritage Site in 1992.

The native language of Taos Pueblo is Northern Tiwa, a member of the Tanoan family of languages. It has been suggested that Northern Tiwa developed when late-arriving Tewa migrants passed across the already-overcrowded Tewa Basin around 1300 CE, and entered into the Pot Creek area to merge with the Tanoans already there.

The "precursor" pueblo to Taos was a pueblo now known as Pot Creek Pueblo. At its height, Pot Creek Pueblo might have been the largest pueblo in the Southwest. However, some kind of trouble developed at Pot Creek in the early 1300s CE, and part of the pueblo was burned with the residents scattering in different directions. Many went a few miles north to a neighboring Tanoan pueblo (Taos) and merged with them. Others went southeast, into a high pass in the mountains where they founded Picuris Pueblo.

Taos Pueblo was a center of trade long before the Spanish arrived. The pueblo served as a contact point between the Rio Grande Pueblos to the south and the Comanche, Apache and Ute to the east, north and northeast. Every fall when the annual trade fair was happening, Taos Pueblo became a neutral zone where fighting and raiding were banned for the duration of the fair. The arrival of the Spanish in 1540 didn't interfere with the trade fair cycle but after they returned in 1598, they did try to impose taxes on everyone.

Around 1620 Jesuit priests oversaw the construction of the first mission of San Geronimo de Taos. Friction between the tribe and the Spanish led to the killing of a resident priest and destruction of the church in 1660. The church was rebuilt, only to be destroyed again and two resident priests killed in the opening moments of the Pueblo Revolt of 1680. The Spanish were evicted from northern Nuevo Mexico that year but returned in force in 1692. By 1700, the third mission church at Taos was under construction.

For a few years, the tribe and the Spanish got along, forced to be amicable in order to deal with their common enemies: Ute, Apache and Comanche raiders. That pressure was relieved in 1776 when Governor Juan Bautista de Anza and his troops killed virtually the entire upper hierarchy of the Comanche tribe in the Battle of Cuerno Verde, near Greenhorn Mountain in southern Colorado.

American fur trappers and traders first appeared in the area in the early 1800s. Things changed in 1820 when Mexico declared independence and trade wagons began rolling over the Santa Fe Trail. The American military arrived in 1847, in the beginning of the Mexican-American War. That military presence quickly led to the Taos Rebellion of 1847, a rebellion which saw Governor Charles Bent and several other prominent Americans killed. A few days later American troops and armed citizens arrived from Santa Fe and, thinking the rebels had taken refuge in the mission church, they destroyed the church and killed many innocent women and children who were hiding inside it. That effectively ended the rebellion. After a short trial, 17 of the surviving rebels were hanged from trees surrounding the plaza in the nearby non-Indian village of Taos. A new mission church was constructed around 1850 near the west gate of the pueblo wall but the ruins of the old church are still visible today.

One result of the Taos Rebellion is that the tribe has never signed a peace treaty with the United States Government. That led to President Theodore Roosevelt using an Executive Proclamation to remove some 48,000 acres of the pueblo's mountain land and combine that with the fledgling Carson National Forest in 1906. That land was a point of major contention between the pueblo and Congress until it was returned to the tribe by President Richard M. Nixon in 1970. An additional 764 acres was returned to the tribe in 1996.

Today the community of Taos Pueblo is considered one of the most private, secretive and conservative of all the pueblos, even though the Pueblo of Taos offers more on-site shops for visitors than any other pueblo.

Taos potters have been making pottery for hundreds of years, much of it slipped with micaceous clay so that it could be used for cooking purposes. For many years Taos pottery was traded to the Apache, Ute, Arapaho and Comanche who came to the annual Taos trade fair, in return for buffalo meat and buffalo hides. Traditional Taos micaceous pottery is known for its glittery tan or yellow gold appearance. Generally, there was no painted decoration but there might be some form of sculpted detail. Today's Taos potters produce a variety of traditional micaceous pots.

100 West San Francisco Street, Santa Fe, New Mexico 87501

(505) 986-1234 - www.andreafisherpottery.com - All Rights Reserved