Daryl Whitegeese

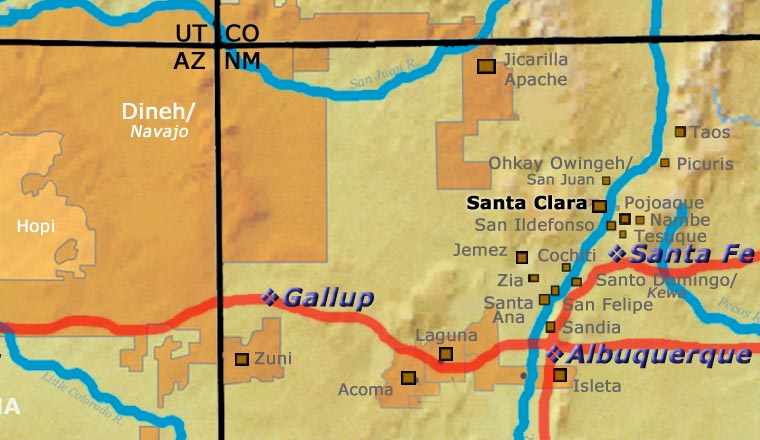

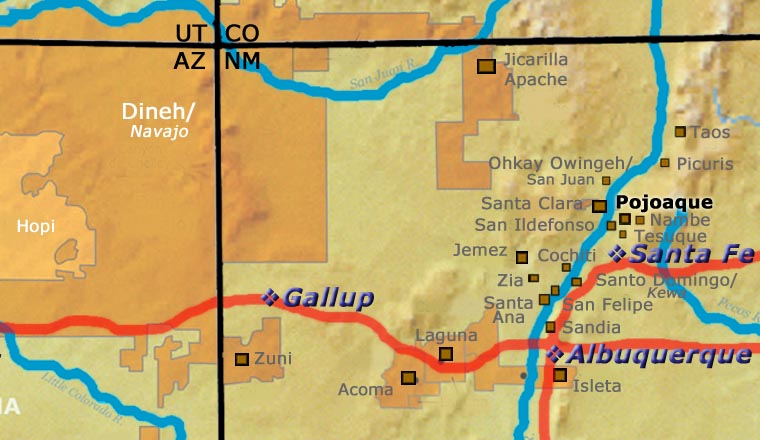

Santa Clara/Pojoaque

Daryl Whitegeese was born in March, 1964 to LuAnn Tafoya of Santa Clara Pueblo and Sosi Tapia of Pojoaque Pueblo. He learned the basics of the traditional art of making pottery from his mother as he was growing up but he also grew up in a family where everyone was a potter. He says he produced his first pot on his own when he was about 32. He enjoyed it so much that by the time he was 40 he was a full-time potter. Prior to that, he'd been working at Digital Equipment Corporation as a systems administrator for 14 years.

After leaving DEC he returned to Santa Clara Pueblo and took on some free-lance computer work. That's how he met his wife, Rosemary Hardy at Pojoaque Pueblo. They were married in 1997 and now have 3 daughters and 3 granddaughters.

Over the years since he began making pots, Daryl has participated in the Santa Fe Indian Market, the Heard Museum Guild Indian Art Fair and the Eiteljorg Museum of the American Indian (in Indianapolis), earning multiple ribbons at all three, including ribbons for Excellence in Traditional Arts, Best of Division, First Place, Second Place, Third Place and Best of Traditional Pottery.

When we asked him where he gets his inspiration he immediately said "Mom and Grandma" (meaning LuAnn and Margaret Tafoya). He said his favorite shape to make is the red water jar with a bear paw imprint, "just like Mom and Grandma used to make." He also loves to decorate his pots with traditional designs, using his own distinctive carving style on a surface polished to a mirror-like, high lustre finish.

While we were talking to him Daryl told us he loves music, especially blues and jazz. He also loves to go to Bronco games in the winter. When he's not busy making pots he's probably somewhere with his family, "spoiling the kids."

Some Awards Earned by Daryl

- 2019 Heard Museum Guild Indian Art Fair & Market, Classification II - Pottery: Best of Classification. Awarded for artwork: Red and White Carved Vase

- 2019 Heard Museum Guild Indian Art Fair & Market, Classification II - Pottery, Division C - Carved, native clay, hand built, fired out-of-doors: First Place. Awarded for artwork: Red and White Carved Vase

- 2018 Heard Museum Guild Indian Art Fair & Market, Classification II - Pottery, Division G - Pottery miniatures not to exceed three (3) inches at its greatest dimension: Honorable Mention. Awarded for artwork: Black Plain Bowl

- 2017 Heard Museum Guild Indian Art Fair & Market. Classification II Pottery, Division G - Pottery miniatures not to exceed three (3) inches at its greatest dimension: Honorable Mention. Awarded for artwork: Black Bear Paw Jar

- 2015 Heard Museum Guild Indian Art Fair & Market, Classification II - Pottery, Best of Class. Awarded for artwork: Black Bear Paw Double Shoulder Water Jar

- 2015 Heard Museum Guild Indian Art Fair & Market, Classification II - Pottery, Division B - Traditional - native clay, hand built, unpainted, including ribbed: First Place. Awarded for artwork: Black Bear Paw Double Shoulder Water Jar

- 2015 Heard Museum Guild Indian Art Fair & Market, Classification II - Pottery, Division C - Traditional - native clay, hand built, carved: First Place. Awarded for Vase

- 2015 Heard Museum Guild Indian Art Fair & Market: Judge's Award - Martha Hopkins Streuver. Awarded for artwork: Black Bear Paw Double Shoulder Water Jar

- 2015 Heard Museum Guild Indian Art Fair & Market: Judge's Award - Dr. Shelby Tisdale. Awarded for artwork: Black Bear Paw Double Shoulder Water Jar

- 2014 Heard Museum Guild Indian Art Fair & Market, Classification II - Pottery: Best of Class

- 2014 Heard Museum Guild Indian Art Fair & Market, Classification II - Pottery, Division B - Traditional, native clay, hand built, unpainted including ribbed: First Place

- 2014 Heard Museum Guild Indian Art Fair & Market, Classification II - Pottery, Division C - Traditional, native clay, hand built, carved: First Place

- 2012 Heard Museum Guild Indian Art Fair & Market, Classification II - Pottery, Division B - Traditional, native clay, hand built, unpainted including ribbed: Second Place

- 2012 Heard Museum Guild Indian Art Fair & Market, Classification II - Pottery, Division C - Traditional, native clay, hand built, carved: Honorable Mention

- 2010 Heard Museum Guild Indian Art Fair & Market, Classification II - Pottery, Division B - Traditional, native clay, hand built, unpainted including ribbed, Honorable Mention

- 2010 Heard Museum Guild Indian Art Fair & Market, Classification II - Pottery, Division C - Traditional, native clay, hand built, carved: Honorable Mention

- 2009 Heard Museum Guild Indian Art Fair & Market, Classification II - Pottery, Division B - Traditional, Native clay, hand built, unpainted: Second Place

- 2008 Heard Museum Guild Indian Art Fair & Market, Classification II - Pottery, Division B - Traditional, Native clay, hand built, unpainted: Second Place

- 2004 Santa Fe Indian Market, Classification II - Pottery, Division C - Traditional pottery, carved or incised in style of San Juan, San Ildefonso, Santa Clara, Category 1003 - Bowls, under 8" in diameter: First Place

100 West San Francisco Street, Santa Fe, New Mexico 87501

(505) 986-1234 - www.andreafisherpottery.com - All Rights Reserved

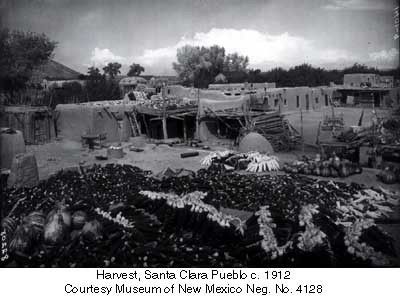

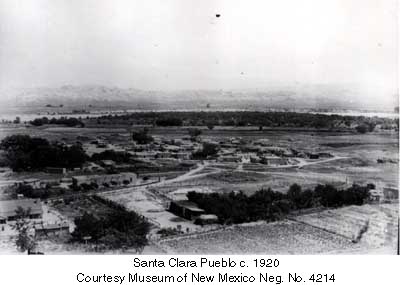

Santa Clara Pueblo

Abandoned Dwellings at Puye Cliffs, Santa Clara Pueblo

Santa Clara Pueblo straddles the Rio Grande about 25 miles north of Santa Fe. Of all the pueblos, Santa Clara has the largest number of potters.

The ancestral roots of the Santa Clara people have been traced to ancient pueblos in the Mesa Verde region in southwestern Colorado. When that area began to get dry between about 1100 and 1300 CE, some of the people migrated eastward, then south into the Chama River Valley where they constructed several pueblos over the years. One was Poshuouinge, built about 3 miles south of what is now Abiquiu on the edge of the Jemez foothills above the Chama River. Eventually reaching two and three stories high, and with up to 700 rooms on the ground floor, Poshuouinge was occupied from about 1375 CE to about 1475. Drought then again forced the people to move, some of them going to the area of Puye (on the eastern slopes of the Pajarito Plateau of the Jemez Mountains) and others downstream to Ohkay Owingeh (San Juan Pueblo, along the Rio Grande). Beginning around 1580 CE, drought forced the residents of the Puye area to relocate closer to the Rio Grande and they founded what we now know as Santa Clara Pueblo on the west bank of the river, with San Juan Pueblo to the north and San Ildefonso Pueblo to the south.

In 1598 the seat of Spanish government was established at Yunque, near San Juan Pueblo. The Spanish proceeded to antagonize the Puebloans so badly that that government was moved to Santa Fe in 1610, for their own safety.

Spanish colonists brought the first missionaries to Santa Clara in 1598. Among the many things they forced on the people, those missionaries forced the construction of the first mission church around 1622. However, like the other pueblos, the Santa Clarans chafed under the weight of Spanish rule. As a result, they were in the forefront of the Pueblo Revolt of 1680. One Santa Clara resident, a mixed black and Tewa man named Domingo Naranjo, was one of the rebellion's ringleaders. However, the pueblo unity that allowed them to chase the Spanish out fell apart shortly after their success, especially after Popé died.

When Don Diego de Vargas came back to the area in 1694, he found most of the Santa Clarans on top of nearby Black Mesa (with the people of San Ildefonso). A six-month siege didn't subdue them so finally, the two sides negotiated a treaty and the people returned to their pueblos. However, successive invasions and occupations by northern Europeans took their toll on all the tribes over the next 250 years. Then the swine flu pandemic in 1918 almost wiped them out.

Today, Santa Clara Pueblo is home to as many as 2,600 people and they comprise probably the largest per capita number of artists of any North American tribe (estimates of the number of potters run as high as 1-in-4 residents).

Today's pottery from Santa Clara is typically either black or red. It is usually highly polished and designs might be deeply carved or etched ("sgraffito") into the pot's surface. The water serpent, (avanyu), is a very common traditional design motif on Santa Clara pottery. Another motif comes from the legend that a bear helped the people find water during a drought. The bear paw has appeared on much of their pottery ever since.

Santa Clara has received a lot of distinction because of the evolving artistry the potters have brought to their craft. Not only did this pueblo produce excellent black and redware, several notable innovations helped move pottery from the realm of utilitarian vessels into the domain of art. Different styles of polychrome redware emerged in the 1920s-1930s. In the early 1960s experiments with stone inlay, incising and double firing began. Modern potters have also extended the tradition with unusual shapes, slips and designs, illustrating what one Santa Clara potter said: "At Santa Clara, being non-traditional is the tradition." (This refers strictly to artistic expression; the method of creating pottery remains traditional).

Santa Clara Pueblo is home to a number of famous pottery families: Tafoya, Baca, Gutierrez, Naranjo, Suazo, Chavarria, Garcia, Vigil, and Tapia - to name a few.

100 West San Francisco Street, Santa Fe, New Mexico 87501

(505) 986-1234 - www.andreafisherpottery.com - All Rights Reserved

Pojoaque Pueblo

Poeh Culture Center at Pojoaque

The Pojoaque Pueblo area seems to have been first settled by pithouse-dwelling Tanoans around 500 CE. A couple hundred years later and the first signs of pottery appeared. Another couple hundred years and the people were beginning to build their structures aboveground. The Tewa flooded down into the valley of the Rio Grande starting in the 1300s, and the population grew until it peaked in the late 1500s. That peak was around the same time the first Spanish arrived. After that, local populations nose-dived as European diseases and Franciscan monks wreaked collossal damage, to the point of actual genocide in some cases (none of the Piro pueblos survived after the 1680 Pueblo Revolt and none of the Tompiro pueblos survived the mid-1700s).

The first Franciscan mission was built at Pojoaque in the early 1600s but the people were already hurting under the impact of Spanish taxes, forced labor and continuous efforts to force conversion to Christianity. That all added up to Pojoaque being in the forefront of the Pueblo Revolt of 1680. Immediately following the revolt, Pojoaque was abandoned and wasn't resettled until about 1706 when many Pojoaque's trickled back from the Cuartelejo area on the plains of eastern Colorado and western Kansas. By then the major Spanish retributions had died down and it was relatively safe to return, surrender and pledge allegiance anew. Franciscans were also being replaced with Jesuits and the religious fervor receded a bit from the heights reached during the Inquisition.

The population of the reestablished pueblo grew slowly but they saw increasing problems from non-Indian encroachment until President Abraham Lincoln recognized the pueblo as an official tribe. Some documents say he awarded the tribe with an official land grant in 1864 and gave a silver cane to the tribe's governor. Other documents say the tribe was given a quit-claim deed... However it worked out, the tribe did gain some legal standing and was able to reestablish its presence until 1900 when a severe smallpox epidemic caused the pueblo to be abandoned again (the Cacique (the tribe's religious leader) died and Governor Jose Antonio Tapia left the reservation to find work).

In 1934 the Commissioner of Indian Affairs placed newspaper ads around the area calling for all Pojoaque tribal members to come back and reoccupy the pueblo lands or tribal ownership would be dissolved under the Indian Re-Organization Act. Shortly, 14 members of the Villareal, Tapia, Romero and Gutierrez/Montoya families were awarded land grants from the Pueblo land base. By 1936 tribal enrollment reached 263 members and Pojoaque became a Federally recognized Indian Reservation.

During the time of abandonment, many Pojoaque tribe members moved to nearby Santa Clara and San Juan Pueblos. Those Pojoaque who were making pottery at the time learned new things from their neighbors and when they later returned to Pojoaque, traditional pottery making changed with all the cross-pollination of styles and designs. Some potters, though, returned to making only traditional Pojoaque styles and designs. Today there is hardly any pottery being made at Pojoaque as so many tribal members are employed in one or another of the tribe's many commercial enterprises.

100 West San Francisco Street, Santa Fe, New Mexico 87501

(505) 986-1234 - www.andreafisherpottery.com - All Rights Reserved