Daisy Hooee Nampeyo

1905-1994

Hopi

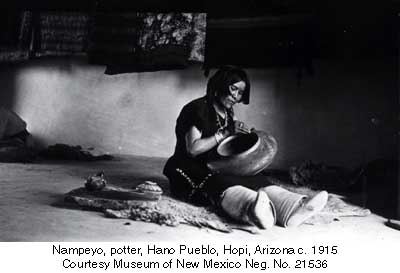

Daisy Hooee Nampeyo was born to Annie and Will Healing of Hano at First Mesa around 1905. Her grandmother was Nampeyo of Hano, her sister Rachel Namingha Nampeyo. Among her aunts and cousins were many of the best Hopi-Tewa potters of the time. The name "Daisy" was most likely given to her by a health care worker on the Hopi Reservation. As her parents were often away from home tending their cattle, Daisy spent significant time in her early years in the care of her grandmother. As she did with all the children in the village, Nampeyo encouraged Daisy to work with clay. When Daisy began making small pots Nampeyo would fire them and take them with her to sell at the store in Polacca. Seeing them for sale alongside Nampeyo's exquisite pieces encouraged Daisy to work harder. Nampeyo also encouraged Daisy to paint freehand and not use a pencil to trace a design on a pot.

Daisy attended the Polacca Day School at first, then moved on to the Phoenix Indian School. At the age of nine she contracted an eye infection that led to the formation of cataracts. When she was twelve a wealthy Californian visiting the area decided to take Daisy under her wing, so to speak, and took her to California to have her eyes treated. Her patroness' name was Anita Baldwin and Daisy lived with her for several years before Anita sent her to L'Ecole des Beaux Arts in Paris, France to study stone carving, painting and ceramics. After Daisy's graduation from there, Anita took her on a tour across Europe, northern Africa, Russia and China, focusing on studying the artwork available in each area.

Daisy returned to the Hopi Reservation about 1930. Her mother had become ill and Daisy returned to work with her and with her sister Fannie. That decision also brought Daisy and her famous grandmother back together. Nampeyo taught Daisy to fire her own pottery and took her along when Nampeyo's family traveled to the Grand Canyon (and other places) to do pottery demonstrations. When Nampeyo's eyesight finally failed, Daisy and Fannie often worked together in decorating pots for her.

From 1935 to 1939 Daisy worked with archaeologists from the Peabody Museum of Harvard University in their excavations at the ruins of Awat'ovi, a village on Antelope Mesa, east of First Mesa. Awat'ovi was first visited by the Spanish in 1540. They returned in 1629 and, after a number of Hopis converted to their form of Christianity, the people of Awat'ovi built the San Bernardo Mission. All the priests were killed in the Pueblo Revolt of 1680 and the mission was partially destroyed. The priests returned in 1699 and, with the help of the people, rebuilt the mission. Then Awat'ovi was destroyed by other Hopis in the beginning of 1701. The archaeologists unearthed whole pots at Awat'ovi and Daisy had the opportunity to examine them while she meticulously copied the designs on them for incorporation into her own designs later on.

Also during her time at Hopi, Daisy married Hopi kachina carver Neil Naha and they had three children before divorcing. After the divorce, Daisy took a job cooking for 4-H boys and girls in the Ramah area on the Zuni Reservation. She was married to Zuni silversmith Leo Poblano for a few years, then he died in an accident in the forest.

Daisy married silversmith Sidney Hooee in 1948. From the early 1960s until she retired in 1974, she carried on the classes of Catalina Zunie and taught ceramics at Zuni High School. That is where one branch of the modern revival of traditional pottery making at Zuni began.

As accomplished a Hopi-Tewa potter as Daisy was, she applied herself to learning Zuni styles, shapes, designs and techniques and soon transformed herself into a complete Zuni potter. Zuni clay is different from Hopi clay but the production process and the designs to decorate with are very similar. Much of Daisy's pottery from those days shows the influence of ancient Zuni pottery traditions like the heartline deer, the rainbird, the deer-in-house and rosette designs, the use of a white clay slip and water jars made in the high shouldered Rio Grande style.

As she had at Hopi, Daisy learned many new designs from the pot sherds she found littering the landscape of Zuni. She often said, "That's where we get the ideas, that's where we get the stories from." After she retired from teaching she continued to teach pottery making (mostly to older women) in her home.

Daisy passed on in 1994 and in 1998, her niece, Dextra Quotskuyva, complimented her work in the course of an interview. "She made big pots, giant pots," said Dextra. In the same interview Dextra also spoke of going to visit Paqua Naha as a child and playing with her cousin Raymond (Daisy's son) on the hill behind Paqua's home.

100 West San Francisco Street, Santa Fe, New Mexico 87501

(505) 986-1234 - www.andreafisherpottery.com - All Rights Reserved

The Hopi People

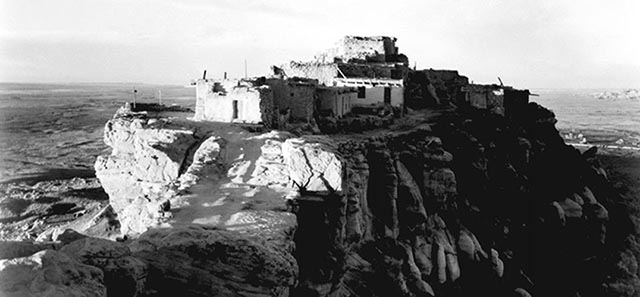

Walpi, as seen by Ansel Adams in 1941

The Hopi People and Their Pottery

Looking across Tewa Village to First Mesa

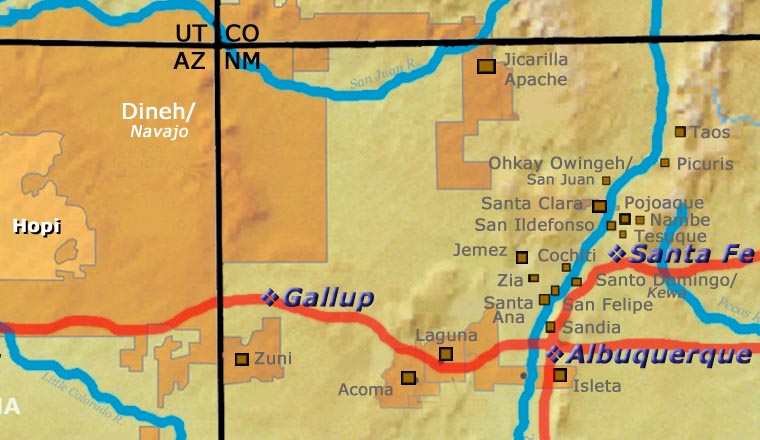

Pottery was being made in the area of the Hopi mesas before generational migrants from the area of central Mexico began to arrive in the 600's. Those migrants brought a much better ceramic technology with them. They also brought a whole new design vocabulary, architectural advancements, more defined rituals and better seeds, along with other agricultural advancements. They spread out across the Southwest between the Colorado River and the Rio Grande, from the Chihuahua and Sonora deserts north to the Great Salt Lake, and they multiplied. The weather of this countryside was very fickle, though, and they had to discover new ways to store their food and keep it good for years. The best tool for preserving things was pottery. Then they began decorating their pottery with their prayers for the seed within, and for the survival of their people.

For hundreds of years those designs were repetitive geometrics, in black-on-white or black-on-gray-white bisques, most matte but more and more polished as time went on. In the 900's, from the south again, figures in black-on-white were introduced. Then came figures and designs in red-and-black-on-white. Then came figures and designs in various combinations of red, black and white on various backgrounds. Each step in the development of decorative and color schemes is reflective of experiential religious developments within one clan or another, one pueblo or another. A lot of what flowered into what we know now as "Sikyátki style and design" was developed in bits and pieces along the rim of Antelope Mesa. It took the experience of Sikyátki to put it all together. Just as the design palette of Sikyátki reached its peak, the village's chief determined they had strayed too far from the traditionally conservative Hopi path and they needed to be put to death for it. He arranged with the elders of Walpi and other villages to have the deed done and sometime in 1625 it was completed. Everyone in the village was killed except for a few ritual specialists who were saved for their spiritual value.

A mural from Awatovi

The styles and designs of Sikyátki lived on on some Awatovi pottery for a few years but the entire design palette changed after the Spanish arrived in force in 1629. San Bernardo Polychrome came into production almost immediately with the reduction in labor force as so many of the Awatovis were forced to serve the priests and build a mission. The design palette changed, too, when all the kachina designs were forced out by the Franciscan priests. Almost everything changed again with the Pueblo Revolt of 1680. There was a general return to themes prevalent before the Spanish arrived across the entire Southwest, except by then most potters were firing their pots using sheep, cow or horse manure. Around the Hopi mesas, a merging of designs and supernaturals with the layouts from the San Bernardo and Sikyatki phases happened. Some archaeologists have termed the pottery that was produced for 100 years after the Pueblo Revolt as "Payupki phase." It faded out around 1780, about the same time the last of the Tiwas and Keresans returned to the Rio Grande Valley from the village of Payupki on Second Mesa. After that came the phases of Polacca Polychrome, including the white-slipped years after the times of drought and disease in the 1800s that were spent at Zuni.

By the mid-1800s, the Hopi pottery tradition had been almost completely abandoned, its utilitarian purposes taken over by cheap enamelware brought in by Anglo traders. Hopi pottery production sputtered along until the 1880's when one woman, Nampeyo of Hano, almost single-handedly revived it. Nampeyo lived in Hano on First Mesa and was inspired by pot sherds found among the nearby ruins of the ancient village of Sikyátki. Like every other potter around First Mesa at the time, Nampeyo was producing jars, bowls and canteens, often with one surface slipped white and decorated with designs in black-and/or-red. At the urging of Anglo traders' Alexander Stephen and Thomas Varker Keam, she began experimenting with polishing the surface of pieces coiled entirely of Jeddito yellow clay and then painting her designs directly on that. Today, credit is given to Nampeyo for fully reviving the Sikyátki style. She was so good that Jesse Walter Fewkes, the first archaeologist to formally excavate Sikyátki, was concerned that her creations would shortly become confused with those made hundreds of years previously.

Sikyátki pottery shapes are very distinctive: flattened jars with wide shoulders; low, open serving bowls decorated inside; seed jars with small openings and flat tops; painting methods of splattering and stippling and very distinctive designs. The Sikyátki style seems to have evolved as various Zuni-, Keres- and Towa-speaking potters came together with Water Clan potters from the Hohokam areas of southern Arizona and northern Mexico, and they began working with clays found in the nearby Jeddito valley area. Over the years, other clans came to the area and made their own contributions to what we now refer to as "Sikyátki Polychrome." According to Jesse Walter Fewkes, that merging of styles, techniques and designs created some of the finest ceramics ever produced in prehistoric North America.

Today's Hopi Pottery

Most Hopi pottery is unmistakable in its shapes, colors and designs. The Hopis are blessed with multiple excellent clay sources, each offering a different deep color after polishing and firing. Most Hopi pottery uses a buff, red, white or yellow clay body. Some kachina carvers make pottery and sometimes carve and etch their surfaces. Most Hopi potters, though, form their pieces and paint their decorations using colors derived from boiled-down plants, watered-down clay and from crushed minerals.

Much of the symbology painted on Hopi pottery is themed with "bird elements:" eagle and parrot tails, feathers, beaks and wings, and with katsinam (images of their gods) and permutations of migration patterns. Many Hopi, Hopi-Tewa and Tewa potters are members of the Corn Clan and their annual religious cycle revolves around the seasons of corn. The vast majority of today's Hopi pottery shapes and the designs painted on them are obvious descendants of the work of potters who existed 200-and-more years ago.

The above paragraph applies mostly to potters from the vicinity of First Mesa. The few potters from Second and Third Mesas seem to derive their design palettes from farther back in time, to the geometric designs, patterns and figures of the rock art prevalent before the advent of the katsinam, and the emergence of the Medicine, Sacred Clown and Warrior societies 800 years ago.

The view south from near Old Oraibi

Other Resources:

100 West San Francisco Street, Santa Fe, New Mexico 87501

(505) 986-1234 - www.andreafisherpottery.com - All Rights Reserved