Zuni

It's a sad fact that in all the arts, everywhere in the word, a high percentage of talented young people drop out and do other things with their lives, and the people in Jennie Laate's classes at Zuni High were no exception. Jennie taught the making of pottery in mostly traditional ways - mostly traditional because the school had an electric kiln and she used it in her classes. So when the students left high school, they no longer had access to that kiln…

Breaking this rule, however, were her brother Anderson Peynetsa and her sister Priscilla. At first Agnes worked with and learned from Anderson, who built a body of work in the mid-1990s which established him as one of Zuni's premier potters. Priscilla also went on to become one of Zuni's finest and most recognized potters. Many of Anderson and Agnes's older, combined effort works are signed "A. A. Peynetsa". Early in her career, Agnes has also worked with Berdel Soseeah.

Agnes digs her own clay locally, grinds it, cleans it, and then forms the pot completely by hand. She also grinds her own slip for the decoration and makes her own paint. However, like most Acoma and Zuni potters, she uses the electric kiln. Defending the use of the electric kiln, the brilliant potter Noreen Simplicio stated in Milford Nahohai's and Elisa Phelp's Dialogues with Zuni Potters: "Over at [Santa Fe] Indian Market, when you try to enter your work, they'll downgrade it because it's fired in a kiln. I think it's good that they have that for people who are totally traditional, but they should have room for people that, like myself, are both traditional and contemporary."

Agnes is both traditional and contemporary in her pottery. According to Allen Hayes and John Blom's "Southwestern Pottery - Anasazi to Zuni": "All Peynetsa work is excellent: excellently decorated, excellently sculpted, often with a quiet sense of humor, never with an inflated sense of importance. "Where else can you see major, museum-quality pieces right alongside a refrigerator magnet, all done with the same loving care?"

100 West San Francisco Street, Santa Fe, New Mexico 87501

(505) 986-1234 - www.andreafisherpottery.com - All Rights Reserved

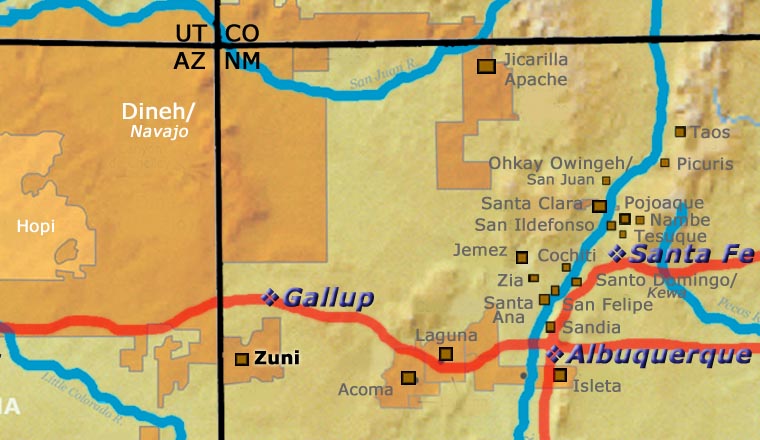

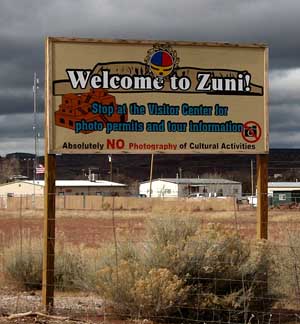

Zuni Pueblo

Welcome sign at Zuni Pueblo

As a tribe, the Zunis seem to have come together between the 13th and 15th centuries CE. It has been speculated that the original source population was of an Ancestral Puebloan lineage out of the environs of Acoma. It has been speculated that they spoke a merged Keres/Tanoan. Then came the migrations out of the White Mountains and eastern Arizona as those areas were abandoned. The newcomers may have brought "Zuni" into the world as they merged into the villages already in place along the Zuni River. They also brought with them artifacts of a desert culture, speculated to have been from a divergent California Penutian source.

In the early 1500s, various Spanish shipwreck survivors and explorers made their way around the southern part of what is now the United States, looking for a way to get back home. While spreading their diseases everywhere they went, they also picked up stories to tell, if and when they got back home. Many of those stories revolved around the "gold" and other "riches" they saw in their travels. Those stories provided the impetus for the Spanish authorities to send out larger militarized forces to explore, conquer and loot.

In 1540, the Zunis fought a major battle with the forces of Francisco Vasquez de Coronado. Coronado was new in the neighborhood and didn't know (or care about) the local customs. His expedition had been sent north from Chihuahua in 1539, expressly to get any gold they could find and bring it back for the king's treasury.

Coronado first approached Hawikuh (the main Zuni pueblo at the time) near the end of a four-day religious festival. The Zunis had spilled a line of corn meal across the ground in front of the main entrance to the pueblo, meant to signify that no one should cross the line and try to enter the village yet. Coronado seems to have interpreted that line of corn meal as an insult and a provocation. He immediately ordered his soldiers to attack.

To get into a pueblo in those days required climbing to the roof first, then climbing down a ladder through a hole in the roof to get inside. The Zunis started throwing rocks down from the roof and almost killed Coronado that way, but his soldiers protected him and they did finally prevail. As Coronado and his men came with horses, cows, sheep, goats and pigs, they were the first livestock the Zunis had ever seen. The "gold" the Spaniards had been told they'd find turned out to be yellow bowls and jars, clay gifts from the Hopis to the Zunis.

Coronado assaulted all seven of the Zuni villages of the time, stealing all their stores of food and destroying their crops while looking for loot. Then he demanded to be told where the gold was. The Zunis didn't know what he was talking about, gold was unknown to them. That's when the Zunis gave him a guide from the eastern Plains, someone who'd somehow made his way as a lone traveler to Hawikuh. While he was promoted as a guide to Coronado and his men, he was instructed by the Zunis to take Coronado far into the Plains and get him lost there. When Coronado finally realized that, more than a year later, he ordered the guide be strangled. Then he turned his men around and headed back to Zuni for supplies, and then he marched on back to Mexico.

When he passed by Zuni in 1542, he left three Mexican Indians and Esteban, a Moorish slave, behind. Esteban apparently shortly assaulted a woman in the village and was immediately killed. The Mexican Indians most likely informed the Zuni leaders of the extent of the Spanish domain in Mexico and the power they exercised there.

In their passage, Coronado and his men also left behind many European diseases, diseases which decimated whole villages across the Southwest. Except for a couple passing exploratory expeditions, though, Zuni was left alone until Don Juan de Oñe arrived at the gate in the 1620s. By that time, so many Zunis had died of Spanish diseases there were only two Zuni villages left. 1628 is when the Franciscan friars arrived. At first the Zunis were friendly with the priests but the forced labor requirements and forced religious conversions wore that welcome out quickly. They forced the people to construct a mission church at Hawikuh in 1629. Relations had changed drastically for the worse by the time of the Pueblo Revolt of 1680. That's when the Zunis killed the priests and burned the missions, but they preserved the relics and icons the priests had brought from Spain.

The tribe built a village near their fortress at Dowa Yalanne (atop a large mesa to the southeast) and prepared to defend their people and way of life against the return of the Spanish army. When Don Diego de Vargas arrived with troops in 1692, he attacked the fortress twice and failed. Then he entered into negotiations with the Zuni war chief and was allowed to climb to the top of Dowa Yalanne. In passing through the village there, he saw many relics from the destroyed missions. With that knowledge, he arranged a peace between the Spanish and the Zunis. Then, between 1693 and 1700, the Zunis consolidated all their small villages into what is now the Pueblo of Zuni.

The railroads arrived in New Mexico in the 1880s and right behind them came the first Anglo traders. Over the next 50 years Zuni pottery turned more and more to what the traders wanted. With the push into mass production, the quality fell off. The end result was the value of Zuni pottery fell way off and the potters tired of what they were doing. Pottery making dropped off in the 1940s until only ceremonial vessels were being made. Catalina Zunie was teaching pottery making at the Zuni Day School through this time period but the Zuni pottery revival didn't really begin until Daisy Hooee began teaching ceramics at Zuni High School in the 1960s and 1970s.

An accomplished Hopi-Tewa potter with an excellent pedigree, Daisy applied herself to learning about Zuni pottery and became a consummate Zuni potter. She retired from teaching at the high school in 1974. Jennie Laate, an Acoma woman who married into Zuni and learned the Zuni way from Daisy Hooee, took over teaching the classes. Many of today's well known Zuni potters thank Jennie Laate for her teaching and inspiration. She taught until 1990 when she turned the classes over to her student, Noreen Simplicio. Noreen taught the classes for 2 years, then Gabriel Paloma took over.

Josephine Nahohai brought traditional Zuni pottery designs back into the community in the 1980s. Les Namingha has also been using more traditional Zuni shapes and designs in his Zuni revival pottery. Today, because so many Zuni potters learned their craft at Zuni High School, they mostly also use electric kilns for firing their works. Other than that, they all use the same traditional methods of gathering and processing the clay, making their pottery and painting their designs, traditional processes that are practiced in virtually the same way in all the pueblos.

100 West San Francisco Street, Santa Fe, New Mexico 87501

(505) 986-1234 - www.andreafisherpottery.com - All Rights Reserved