Linda Askan

Santa Clara

Linda Askan was born into the Santa Clara Summer Clan as the daughter of Marie and Andy Askan (Dineh). She grew up with her mother's family at Santa Clara Pueblo. Her Tewa name, given to her by her grandmother, Adelaide Sisneros, is Jo Povi, meaning "Cactus Flower." Linda attended the Institute of American Indian Arts and worked as a Respiratory Therapy Technician before she decided to become a full-time potter.

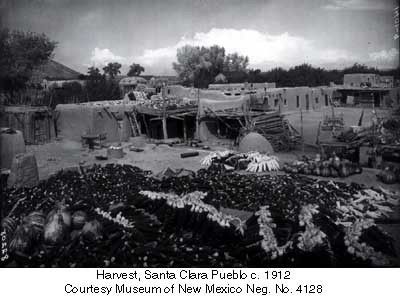

Her grandmother and her mother were influential in teaching Linda the traditional ways to make pottery as she grew up. As a child she played with broken pieces of clay. Then she started polishing the broken pieces with a stone. Putting her hands to the clay and creating something with it was a natural evolution after that. "We would fire together at my grandparents' corral," she remembers. The traditional method leads to firing outside over an open fire, using cottonwood, piñon pine and dry horse manure for fuel. She says, "We experience firing visually: paying attention to the fire, making sure it's evenly burning, being aware the whole time."

Her miniature nativity sets with thumb-size figures have become collector's items. Evolving over time, her sets often reference sources in Dineh culture with details in the blankets her figures wear. The wise men are modeled after buffalo, deer or eagle dancers, each wearing the respective traditional headgear and robe or blanket. She says she began making her figures this way after participating in the Santa Clara Pueblo Buffalo Dance as a dancer. "I felt the dance," she says. "It was very different from watching, more uplifting to your spirit."

"I make my sets in miniature because it's a size that people can afford," she says. She told us her nativities are designed to carry a powerful and simple message: "Our sacred relationship with the land, the sky, the animals and the elements, is passed down through the generations, from grandmother to daughter to granddaughter." Linda has two daughters, Diana and Rose, and she has taught both the traditional art of pottery making.

100 West San Francisco Street, Santa Fe, New Mexico 87501

(505) 986-1234 - www.andreafisherpottery.com - All Rights Reserved

Santa Clara Pueblo

Ruins at Puye Cliffs, Santa Clara Pueblo

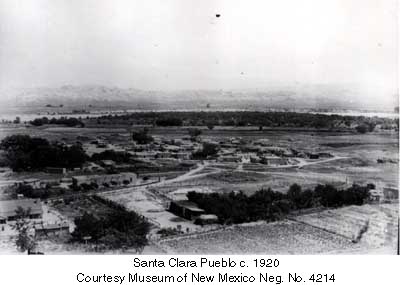

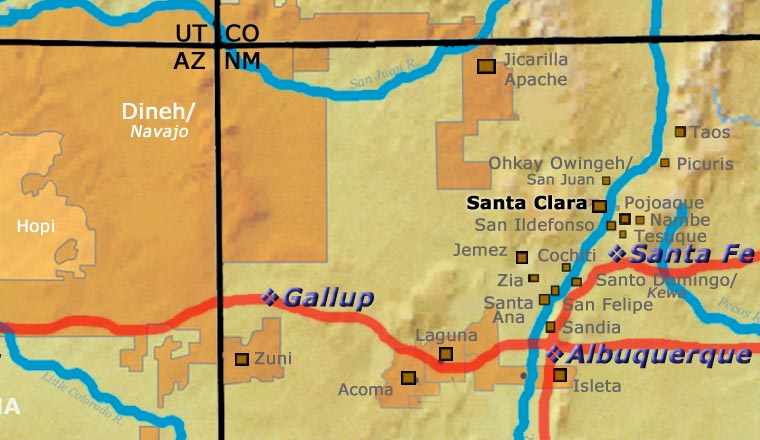

Santa Clara Pueblo straddles the Rio Grande about 25 miles north of Santa Fe. Of all the pueblos, Santa Clara has the largest number of potters.

The ancestral roots of the Santa Clara people have been traced to ancient pueblos in the Mesa Verde region in southwestern Colorado. When that area began to get dry between about 1100 and 1300 CE, some of the people migrated eastward, then south into the Chama River Valley where they constructed several pueblos over the years. One was Poshuouinge, built about 3 miles south of what is now Abiquiu on the edge of the Jemez foothills above the Chama River. Eventually reaching two and three stories high, and with up to 700 rooms on the ground floor, Poshuouinge was occupied from about 1375 CE to about 1475. Drought then again forced the people to move, some of them going to the area of Puye (on the eastern slopes of the Pajarito Plateau of the Jemez Mountains) and others downstream to Ohkay Owingeh (San Juan Pueblo, along the Rio Grande). Beginning around 1580 CE, drought forced the residents of the Puye area to relocate closer to the Rio Grande and they founded what we now know as Santa Clara Pueblo on the west bank of the river, with San Juan Pueblo to the north and San Ildefonso Pueblo to the south.

In 1598 the seat of Spanish government was established at Yunque, near San Juan Pueblo. The Spanish proceeded to antagonize the Puebloans so badly that that government was moved to Santa Fe in 1610, for their own safety.

Spanish colonists brought the first missionaries to Santa Clara in 1598. Among the many things they forced on the people, those missionaries forced the construction of the first mission church around 1622. However, like the other pueblos, the Santa Clarans chafed under the weight of Spanish rule. As a result, they were in the forefront of the Pueblo Revolt of 1680. One Santa Clara resident, a mixed black and Tewa man named Domingo Naranjo, was one of the rebellion's ringleaders. However, the pueblo unity that allowed them to chase the Spanish out fell apart shortly after their success, especially after Popé died.

When Don Diego de Vargas came back to the area in 1694, he found most of the Santa Clarans on top of nearby Black Mesa (with the people of San Ildefonso). A six-month siege didn't subdue them so finally, the two sides negotiated a treaty and the people returned to their pueblos. However, successive invasions and occupations by northern Europeans took their toll on all the tribes over the next 250 years. Then the swine flu pandemic in 1918 almost wiped them out.

Today, Santa Clara Pueblo is home to as many as 2,600 people and they comprise probably the largest per capita number of artists of any North American tribe (estimates of the number of potters run as high as 1-in-4 residents).

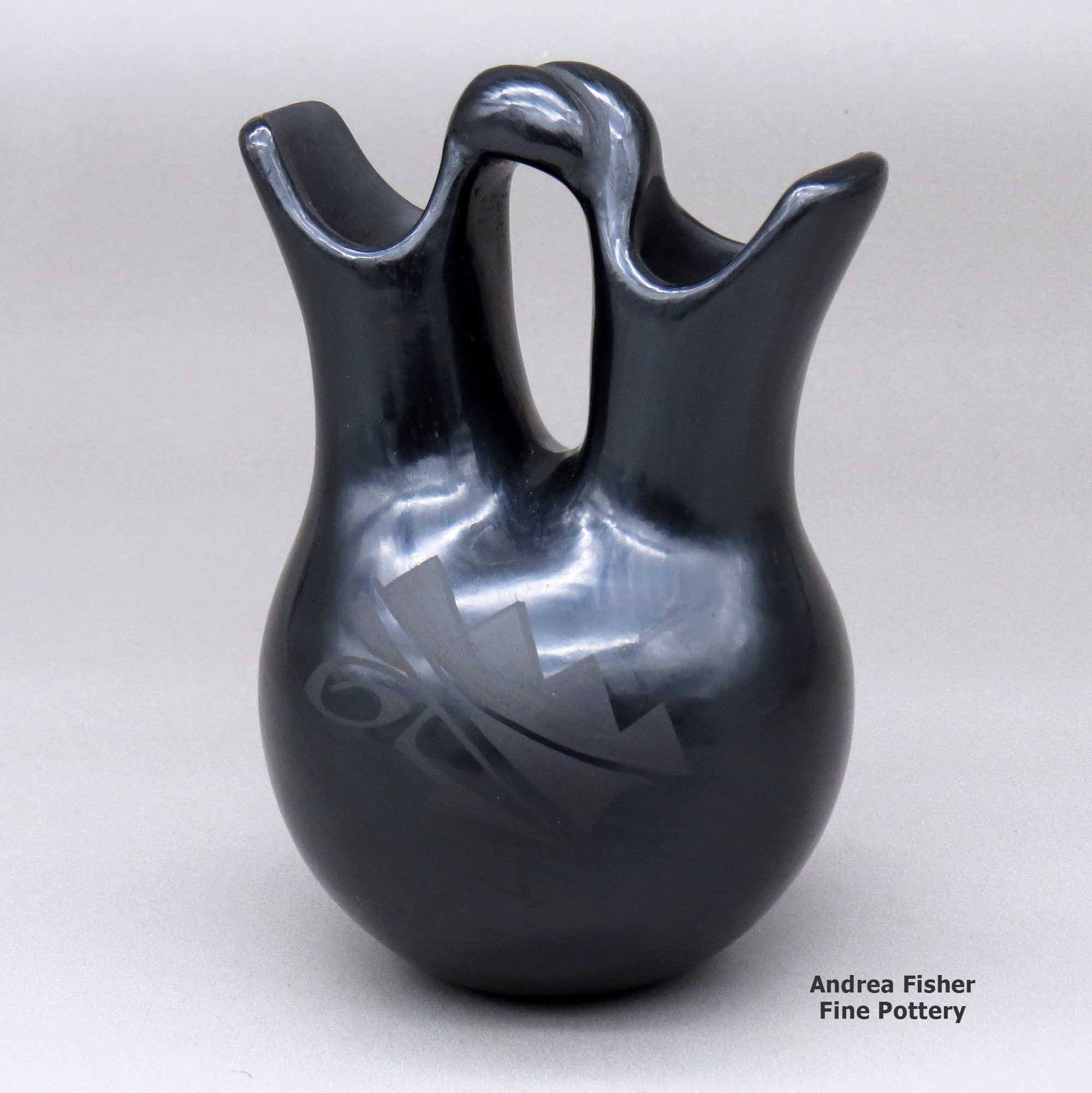

Today's pottery from Santa Clara is typically either black or red. It is usually highly polished and designs might be deeply carved or etched ("sgraffito") into the pot's surface. The water serpent, (avanyu), is a very common traditional design motif on Santa Clara pottery. Another motif comes from the legend that a bear helped the people find water during a drought. The bear paw has appeared on much of their pottery ever since.

Santa Clara has received a lot of distinction because of the evolving artistry the potters have brought to their craft. Not only did this pueblo produce excellent black and redware, several notable innovations helped move pottery from the realm of utilitarian vessels into the domain of art. Different styles of polychrome redware emerged in the 1920s-1930s. In the early 1960s experiments with stone inlay, incising and double firing began. Modern potters have also extended the tradition with unusual shapes, slips and designs, illustrating what one Santa Clara potter said: "At Santa Clara, being non-traditional is the tradition." (This refers strictly to artistic expression; the method of creating pottery remains traditional).

Santa Clara Pueblo is home to a number of famous pottery families: Tafoya, Baca, Gutierrez, Naranjo, Suazo, Chavarria, Garcia, Vigil, and Tapia - to name a few.

100 West San Francisco Street, Santa Fe, New Mexico 87501

(505) 986-1234 - www.andreafisherpottery.com - All Rights Reserved

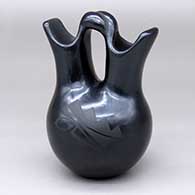

Santa Clara

$ 475

zzsc4f052m1

A black-on-black wedding vase with a twisted bridge and a two-panel geometric design

3.5 in L by 4 in W by 5.5 in H

Condition: Excellent

Signature: Linda Askan Santa Clara Pueblo

Date Created: 2024

100 West San Francisco Street, Santa Fe, New Mexico 87501

(505) 986-1234 - www.andreafisherpottery.com - All Rights Reserved

The Story of

the Wedding Vase

as told by Teresita Naranjo of Santa Clara Pueblo

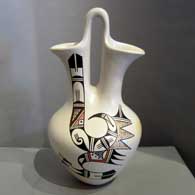

Helen Naha

Hopi

Wilma Baca Tosa

Jemez Pueblo

Margaret Tafoya

Santa Clara Pueblo

The Wedding Vase has been used for a long, long time in Indian Wedding Ceremonies.

After a period of courtship, when a boy and girl decide to get married, they cannot do so until certain customs have been observed. The boy must first call all his relatives together to tell them that he desires to be married to a certain girl. If the relatives agree, two or three of the oldest men are chosen to call on the parents of the girl. They pray according to Indian custom and the oldest man will tell the parents of the girl what their purpose is in visiting. The girl's parents never give a definite answer at this time, but just say that they will let the boy's family know their decision later.

About a week later, the girl calls a meeting of her relatives. The family then decides what answer should be given. If the answer is “no” that is the end of it. If the answer is “yes” then the oldest men in her family are delegated to go to the boy's home, and to give the answer, and to tell the boy on what day he can come to receive his bride-to-be. The boy must also notify all of his relatives on what day the girl will receive him, so that they will be able to have gifts for the girl.

Now the boy must find a Godmother and Godfather. The Godmother immediately starts making the wedding vase so that it will be finished by the time the girl is to be received. The Godmother also takes some of the stones which have been designated as holy and dips them into water, to make it holy water. It is with this holy water that the vase is filled on the day of the reception.

The reception day finally comes and the Godmother and Godfather lead the procession of the boy's relatives to the home of the girl. The groom is the last in line and must stand at the door of the bride's home until the gifts his relatives have brought have been opened and received by the bride.

The bride and groom now kneel in the middle of the room with the groom's relatives and the bride's parents praying all around them. The bride then gives her squash blossom necklace to the groom's oldest male relative, while the groom gives his necklace to the bride's oldest male relative. After each man has prayed, the groom's necklace is placed on the bride, and the bride's is likewise placed on the groom.

After the exchange of squash blossom necklaces and prayers, the Godmother places the wedding vase in front of the bride and groom. The bride drinks out of one side of the wedding vase and the groom drinks from the other. Then, the vase is passed to all in the room, with the women all drinking from the bride's side, and the men from the groom's.

After the ritual drinking of the holy water and the prayers, the bride's family feeds all the groom's relatives and a date is set for the church wedding. The wedding vase is now put aside until after the church wedding.

Once the church wedding ceremony has occurred, the wedding vase is filled with any drink the family may wish. Once again, all the family drinks in the traditional manner, with women drinking from one side, and men the other. Having served its ceremonial purpose, the wedding vase is given to the young newlyweds as a good luck piece.