Alice Cling

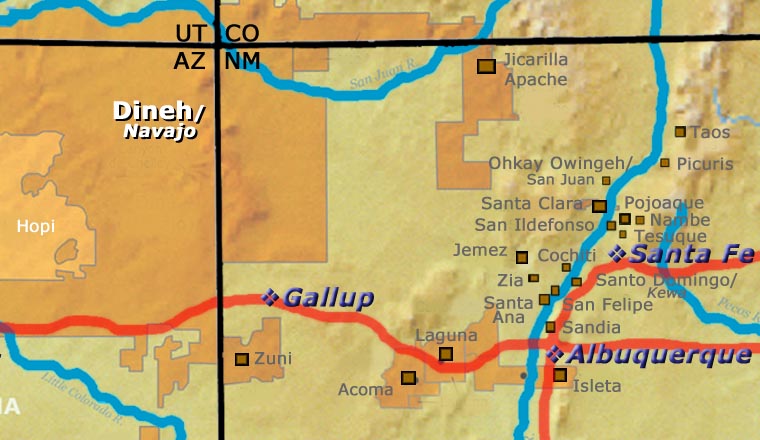

Dineh (Navajo)

Born in 1946 at Cow Springs (near Tonalea, Arizona), Alice has lived most of her life in the area west of Kayenta and north of Black Mesa. She learned the Dineh way of making pottery from her mother, Rose Williams, and her aunt, Grace Barlow.

Dineh pottery is a relatively recent phenomenon as they were traditionally a nomadic tribe who stored all their foodstuffs in pitch-coated baskets. The nomadic way of life made ceramic pottery impractical for several reasons, the weight and fragility of pottery being at the top of that list. Also, unlike Hopi, Acoma and Zuni potters, those few who made Dineh pottery for ceremonial and personal use were never approached by the early railroad tourist promoters to produce pots on a commercial basis.

The Dineh learned much of the traditional methods of making pottery from their Puebloan neighbors after they settled in the Four Corners region about the same time the Spanish first appeared in the Southwest. They did produce a significant amount of utilitarian and ceremonial pottery through the 1700s and early 1800s but after the railroads arrived, it was too easy to purchase metal pots and pans. Dineh pottery production of all sorts virtually stopped. By the early 1950s, only potters in the Shonto/Cow Springs area were still producing any amount of Dineh pottery and it was Bill Beaver, a non-Dineh trader at the Shonto Trading Post who spurred the revival and stimulated the market for Dineh pottery. As the tourist trade increased, so did the demand for Dineh pottery. However, there has always been a religious prohibition on painted pottery designs among the Dineh and that prohibition is still widely observed.

Alice started dabbling with clay as a young girl and became a recognized Dineh potter only in the late 1980s, after graduating from high school and returning to the Shonto area. She digs her clay from a special place near Black Mesa. She applies an iron-bearing slip to her finished dry clay forms and polishes the surfaces with either a river stone or a Popsicle stick. When firing, the ash that falls onto the pots from the juniper wood-fueled pit fire combines with the clay to produce the red-orange-purple-brown-black blushes (also known as fire clouds) on her pottery. After firing, she usually applies a light coating of warm piñon pine pitch and burnishes each pot to a distinctive low sheen.

Alice's personal contribution to the renaissance of Dineh pottery is the magnificent coloration she achieves on her softly burnished forms. Except for fire clouds and the occasional raised rope or biyo' around the shoulder or the opening, her pots are undecorated.

One of Alice's pieces was exhibited in the Vice-Presidential Mansion in Washington, DC, in 1978 and her career took off from there. Her elegant, gracefully austere pots are included with the avant-garde potters in Pottery by American Indian Women, the Legacy of Generations exhibition and book by Susan Peterson, 1997, at the National Museum of Women in the Arts, Washington, D.C. Alice earned numerous awards from nearly every Market and show she entered in the 19 years between those two events. Alice hasn't entered as many juried competitions in the years since 1997 but she still produces beautiful pottery in the ancient way.

Some Exhibits that have Featured Alice's Work

- Our Stories: American Indian Art and Culture in Arizona. Heard Museum West. Surprise, AZ. June 2006 - October 2009

- The Navajo Folk Art Festival. Heard Museum North. Scottsdale, AZ. February 2002

- Fabric, Wood and Clay: Diverse World of Navajo Art. Heard Museum North. Scottsdale, AZ. January 2002 - July 2002

- Indian Market: New Directions in Southwestern Native American Pottery. Peabody Essex Museum. Salem, MA. November 2001 - March 2002

- The Art of the People. Gallup Cultural Center. Gallup, NM. August 2001

- The Legacy of Generations: Pottery by American Indian Women. Heard Museum. Phoenix, AZ. February 14, 1998 - May 17, 1998

- The Legacy of Generations: Pottery by American Indian Women. The Museum of Women in the Arts. Washington, DC. October 9, 1997 - January 11,1998

- Contemporary Art of the Navajo Nation. Cedar Rapids Museum of Art. Cedar Rapids, IA. 1994

- The Navajo Show and Sale. Arizona State Museum, University of Arizona. Tempe, AZ. December 1988

- Anii Ánáádaalyaa̕ ígíí (Recent Ones That Are Made): Continuity & Innovation in Recent Navajo Art. Wheelwright Museum of the American Indian. Santa Fe, New Mexico. July 10, 1988 - October 30, 1988

- In the Spirit of Tradition: The Heard Museum Craft Arts Invitational. Heard Museum. Phoenix, AZ. March 1986 - May 1986

- Alice Cling. Navajo Tribal Museum. Window Rock, Arizona. May 13-30, 1985

Some Awards Alice Earned

- 2004 Santa Fe Indian Market, Classification II - Pottery, Division A - Traditional unpainted pottery: Best of Division

- 2004 Santa Fe Indian Market, Classification II - Pottery, Division A - Traditional unpainted pottery, Category 801 - Navajo style all forms: First Place

- 2001 Santa Fe Indian Market, Classification II - Pottery, Division A - Traditional unpainted pottery, Category 801 - Navajo style alternate forms: First Place

- 2001 Santa Fe Indian Market, Classification II - Pottery, Division A - Traditional unpainted pottery, Category 801 - Navajo style alternate forms: Third Place

- 1998 Santa Fe Indian Market, Classification II - Pottery, Division A - Traditional unpainted pottery, Category 801 - Navajo style, jars (with or without handles or lids): Second Place

- 1998 Santa Fe Indian Market, Classification II - Pottery, Division A - Traditional unpainted pottery, Category 801 - Navajo style, jars (with or without handles or lids): Third Place

- 1998 Santa Fe Indian Market, Classification II - Pottery, Division A - Traditional unpainted pottery, Category 802 - Navajo style, other forms: Third Place

- 1994 Santa Fe Indian Market, Classification II - Pottery, Division A - Traditional unslipped and unpainted pottery, Category 801 - Navajo style: Second Place

- 1993 Santa Fe Indian Market, Classification II - Pottery, Division A - Unslipped pottery, Category 801 - Navajo style: First Place

- 1992 Santa Fe Indian Market, Classification II - Pottery, Division A - Traditional unslipped and unpainted pottery, Category 801 - Navajo style: First Place

- 1992 Santa Fe Indian Market, Classification II - Pottery, Division J - Non-traditional, any forms: Best of Division

- 1992 Santa Fe Indian Market, Classification II - Pottery, Division J - Non-traditional, any forms, Category 1611 - Miscellaneous: First Place

- 1991 Santa Fe Indian Market, Classification II - Pottery, Division A - Traditional unslipped pottery, Category 801 - Navajo style: Second Place

- 1989 Santa Fe Indian Market, Classification II - Pottery, Division A - Traditional, Category 701 - Navajo pottery: First Place

- 1989 Santa Fe Indian Market, Classification II - Pottery, Division A - Traditional, Category 701 - Navajo pottery: Second Place

- 1988 Navajo Nation Fair Arts and Crafts Competition, Classification III - Pottery, patch-coated, Navajo: Best in Class and First Place

- 1988 Navajo Nation Fair Arts and Crafts Competition, Classification III - Pottery, patch-coated, Navajo: First Place

- 1987 Gallup InterTribal Ceremonial, Classification IV - Pottery, undecorated, any object: First Place

- 1983 Santa Fe Indian Market, Classification II - Pottery, Division A - Traditional unslipped and unpainted: First Place

100 West San Francisco Street, Santa Fe, New Mexico 87501

(505) 986-1234 - www.andreafisherpottery.com - All Rights Reserved

Dineh

A view in Monument Valley

The Dineh refers to themselves as "Dineh" because the word means "the People" in their language. "Navajo" is a name that was given to them by the early Spanish. Historical and archaeological evidence points to the Dineh people entering the Southwest around 1400 CE. Their oral history still contains stories of that migration as the journey began in eastern Alaska and northwestern Canada centuries after their ancestors made the journey across the Bering Land Bridge from central Asia about 10,000 years ago. They were primarily hunter-gatherers until they came into contact with the Pueblo peoples and learned the basics of survival in this drier climate. Dineh oral history points to a long relationship between the Dineh and the Puebloans as they learned from and traded with each other.

When the Spanish first arrived, the Dineh occupied much of the area between the San Francisco Peaks (in Arizona), Hesperus Mountain and Blanca Peak (in Colorado) and Mount Taylor (in New Mexico). Spanish records indicate they traded bison meat, hides and stone to the Puebloans in exchange for maize and woven cotton goods. It was the Spanish who brought sheep to the New World and the Dineh took to sheep-herding quickly with sheep becoming a form of currency and sign of wealth.

When the Americans arrived in 1846, things began to change. The first fifteen years were marked by broken treaties and increasing raids and animosities on both sides. Finally, Brigadier General James H. Carleton ordered Colonel Kit Carson to round up the Dineh and transport them to Bosque Redondo in eastern New Mexico for internment. Carson succeeded only by engaging in a scorched earth campaign in which his troops swept through Dineh country killing anyone carrying a weapon and destroying any crops, livestock and dwellings they found. Facing starvation and death, the last band of Dineh surrendered at Canyon de Chelly.

Carson's campaign then led straight into "the Long Walk" to Bosque Redondo, a 300-mile trek during which at least 10% of the people died along the way. At Bosque Redondo they discovered the government had not allocated an adequate supply of water, livestock, provisions or firewood to support the 4,000-5,000 people interned there. The Army also did little to protect them from raids by other tribes or by Anglo citizens. The failure was such that the Federal government and the Dineh negotiated a treaty that allowed the people to return to a reservation that was only a shadow of their former territory little more than a couple years after they had left. However, succeeding years have seen additions to the reservation until today it is the largest Native American Reservation in the 48 contiguous states.

Large deposits of uranium were discovered on the Navajo Nation after World War II but the mining that followed ignored basic environmental protection for the workers, waterways and land. The Dineh have made claims of high rates of cancer and lung disease from the environmental contamination but the Federal government has yet to offer comprehensive compensation.

As a semi-nomadic tribe, the Dineh never made much pottery, preferring to use baskets for most storage purposes. They did produce a small amount of pottery for ceremonial uses. Once they were settled on a reservation, pottery began to make more sense. From a beginning making simple wares for colonial estates they transformed their pottery into art. After 1950 Cow Springs brownware began to appear on the market. A trader named Bill Beaver was in Shonto back then, encouraging local potters to "make something different" and the market in the outside world responded positively to those different creations.

Rose Williams is considered the matriarch of modern Dineh pottery. She learned from Grace Barlow (her aunt) and passed her knowledge and experience on to her daughters and many others. Today, most Dineh pottery is heavy, thick-walled and coated with pine pitch (a sealer they also use on many of their baskets). Most Dineh pottery has little in the way of decoration but many pieces have a biyo' (a traditional decorative fillet) around the rim. Unlike Puebloan potters, Dineh potters do not grind up old pot sherds and use them for temper in creating new pottery. Their religion says those pot sherds are infused with the spirits of their ancestors and that forbids the reuse of the material. Similarly, Dineh religion limits Dineh potters to using primarily Dineh carpet designs in the decoration of their pots.

Dineh potters have also created a panoply of folk art, including unfired clay creations called "mud toys." Other Dineh potters, like Christine McHorse, have graduated into the mainstream of American Ceramic Art and easily compete among the finest ceramic artists on Earth.

100 West San Francisco Street, Santa Fe, New Mexico 87501

(505) 986-1234 - www.andreafisherpottery.com - All Rights Reserved

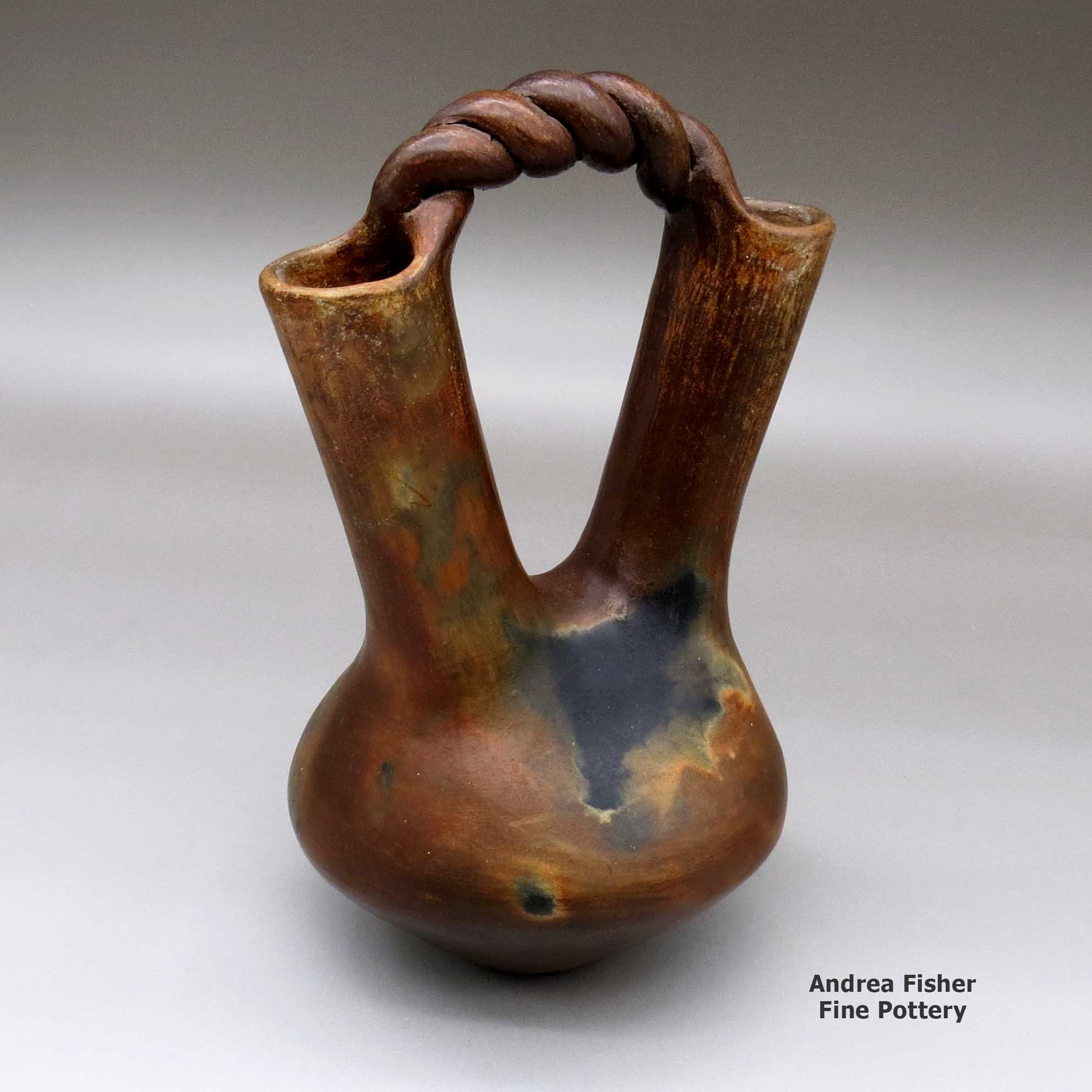

Dineh

$ 295

cjnv4e212

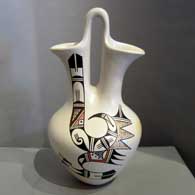

A plain brown wedding vase with a twisted bridge and fire clouds

6.75 in L by 8.5 in W by 12.25 in H

Condition: Very good with age appropriate wear

Signature: Sticker on bottom: Alice Williams Corn Springs

100 West San Francisco Street, Santa Fe, New Mexico 87501

(505) 986-1234 - www.andreafisherpottery.com - All Rights Reserved

The Story of

the Wedding Vase

as told by Teresita Naranjo of Santa Clara Pueblo

Helen Naha

Hopi

Wilma Baca Tosa

Jemez Pueblo

Margaret Tafoya

Santa Clara Pueblo

The Wedding Vase has been used for a long, long time in Indian Wedding Ceremonies.

After a period of courtship, when a boy and girl decide to get married, they cannot do so until certain customs have been observed. The boy must first call all his relatives together to tell them that he desires to be married to a certain girl. If the relatives agree, two or three of the oldest men are chosen to call on the parents of the girl. They pray according to Indian custom and the oldest man will tell the parents of the girl what their purpose is in visiting. The girl's parents never give a definite answer at this time, but just say that they will let the boy's family know their decision later.

About a week later, the girl calls a meeting of her relatives. The family then decides what answer should be given. If the answer is “no” that is the end of it. If the answer is “yes” then the oldest men in her family are delegated to go to the boy's home, and to give the answer, and to tell the boy on what day he can come to receive his bride-to-be. The boy must also notify all of his relatives on what day the girl will receive him, so that they will be able to have gifts for the girl.

Now the boy must find a Godmother and Godfather. The Godmother immediately starts making the wedding vase so that it will be finished by the time the girl is to be received. The Godmother also takes some of the stones which have been designated as holy and dips them into water, to make it holy water. It is with this holy water that the vase is filled on the day of the reception.

The reception day finally comes and the Godmother and Godfather lead the procession of the boy's relatives to the home of the girl. The groom is the last in line and must stand at the door of the bride's home until the gifts his relatives have brought have been opened and received by the bride.

The bride and groom now kneel in the middle of the room with the groom's relatives and the bride's parents praying all around them. The bride then gives her squash blossom necklace to the groom's oldest male relative, while the groom gives his necklace to the bride's oldest male relative. After each man has prayed, the groom's necklace is placed on the bride, and the bride's is likewise placed on the groom.

After the exchange of squash blossom necklaces and prayers, the Godmother places the wedding vase in front of the bride and groom. The bride drinks out of one side of the wedding vase and the groom drinks from the other. Then, the vase is passed to all in the room, with the women all drinking from the bride's side, and the men from the groom's.

After the ritual drinking of the holy water and the prayers, the bride's family feeds all the groom's relatives and a date is set for the church wedding. The wedding vase is now put aside until after the church wedding.

Once the church wedding ceremony has occurred, the wedding vase is filled with any drink the family may wish. Once again, all the family drinks in the traditional manner, with women drinking from one side, and men the other. Having served its ceremonial purpose, the wedding vase is given to the young newlyweds as a good luck piece.