Click or tap to see a larger version

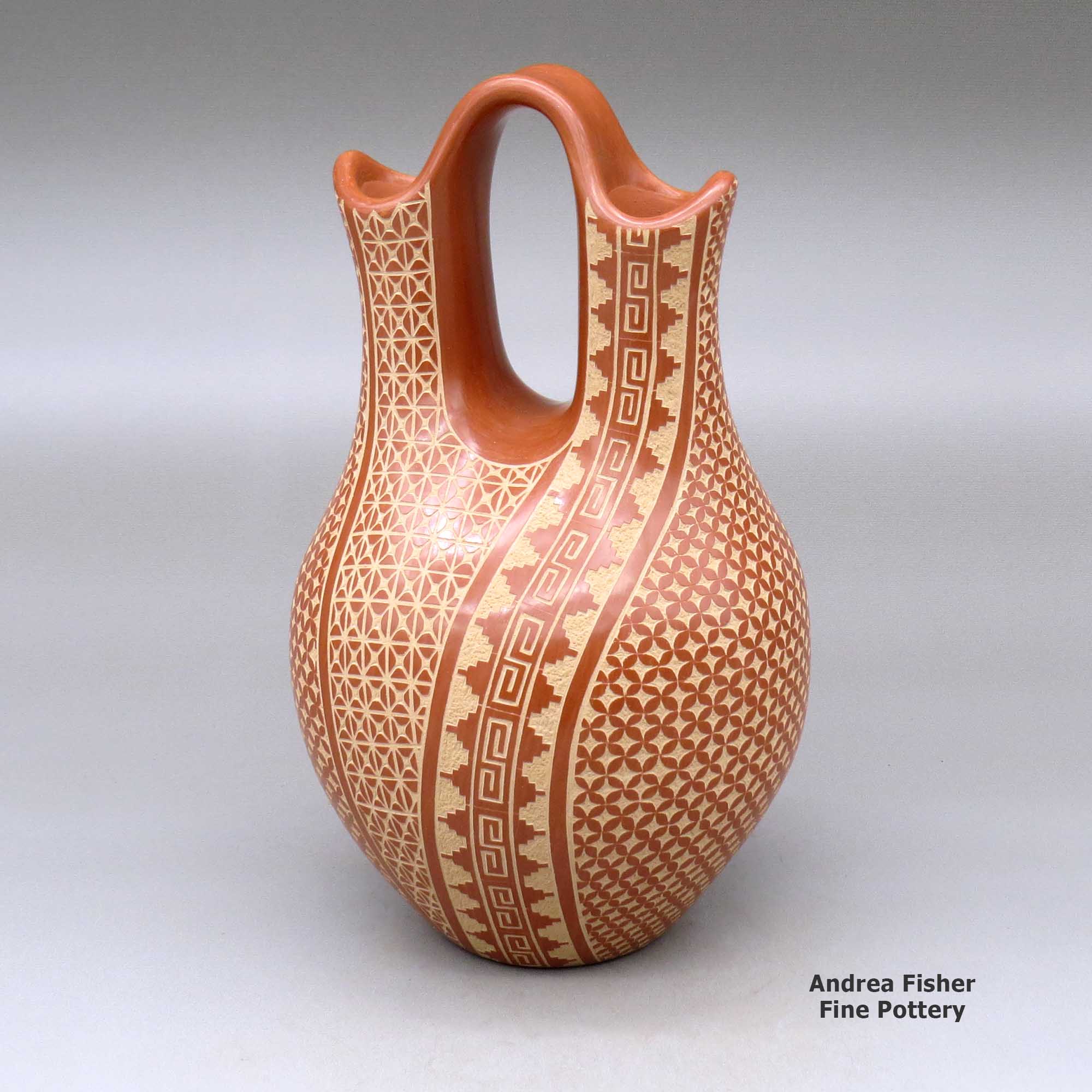

Wilma Baca Tosa, Jemez, A red wedding vase decorated with a sgraffito snowflake, scroll and geometric design

Jemez

$ 1150

zzje5b170

A red wedding vase decorated with a sgraffito snowflake, scroll and geometric design

5.75 in L by 5.75 in W by 9.75 in H

Condition: Excellent

Signature: Wilma Baca Tosa Jemez

Date Created: 2025

Tell me more! Buy this piece!

(505) 986-1234 - www.andreafisherpottery.com - All Rights Reserved

Wilma Baca Tosa

Jemez

Wilma Baca, (New Wheat), was born to John and Linda Baca of Jemez Pueblo in September 1967. She was inspired to make pottery by her grandmother, Marie Reyes Shendo. Marie taught Wilma the fundamentals of making pottery the traditional way using ancient methods passed down from their ancestors.

Wilma specializes in hand coiled, stone polished and traditionally decorated Jemez pottery. She makes redware bowls, jars, seed pots, vases and wedding vases. She has been etching her pottery using the free-hand sgraffito technique since 1989. Her favorite piece to make is the wedding vase because of its meaning: "The spouts represent two separate lives, the bridge across the middle unites these separate lives as one," she says.

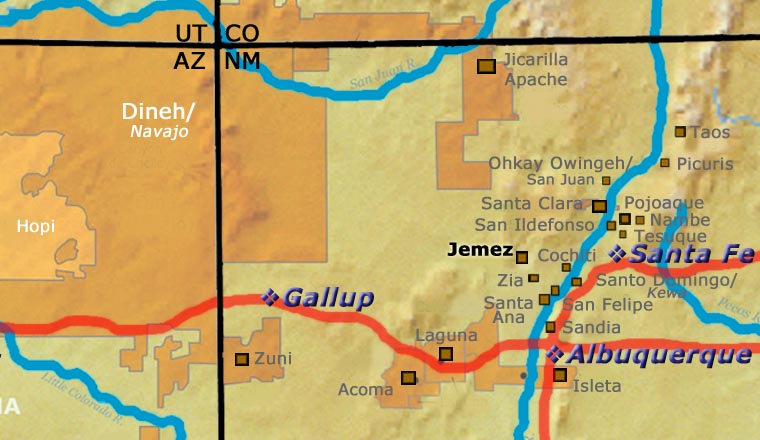

Jemez Pueblo

Ruins of San Jose de las Jemez Mission

As the drought in the Four Corners region deepened in the late 1200s, several clans of Towa-speaking people migrated southeastward from the Four Corners area to the Canyon de San Diego area the southern Jemez mountains, in what is now north-central New Mexico. Other clans of Towa-speaking people migrated southwest and settled in the Jeddito Wash area, below Antelope Mesa and southeast of Hopi First Mesa, in what is now northeastern Arizona. The migrations began in earnest in the mid 1200s and were mostly complete by the mid 1300s.

Archaeologist Jesse Walter Fewkes argues that potsherds found in the vicinity of the ruin at Sikyátki (near the foot of Hopi First Mesa) speak to the strong influence of earlier Towa-speaking potters on what became "Sikyátki Polychrome" pottery (Sikyátki was a village at the foot of First Mesa, destroyed before the first Hopi contact with the Spanish in 1540). Fewkes maintained that Sikyátki Polychrome pottery was the finest ceramic ware ever made in prehistoric North America.

Francisco de Coronado and his men arrived in the Jemez Mountains of Nuevo Mexico in 1539. By then the Jemez people had built several large masonry villages among the canyons and on some high ridges in the area. Their population was estimated at about 30,000 and they were among the largest and most powerful tribes in northern New Mexico. Some of their pueblos reached five stories high and contained as many as 3,000 rooms.

Because of the nature of the landscape they inhabited, growing food was very hard. So the Jemez became traders, too, and their people traded goods all over the Southwest and northern Mexico.

The arrival of the Spanish was disastrous for the Jemez and they resisted the Spanish with all their might. That led to many atrocities against the tribe until they rose up in the Pueblo Revolt of 1680 and evicted the Spanish from northern New Mexico. With the Spanish gone, the Jemez destroyed much of what they had built on Jemez land. Then they concentrated on preparing themselves for the eventual return of the hated priests and the Spanish military.

The Spanish returned in 1692 and their efforts to retake northern New Mexico bogged down as the Jemez fought them doggedly for four years. In 1696 many Jemez came together, killed a Franciscan missionary and then fled to join their distant relatives in the Jeddito Wash area. They remained at Jeddito Wash for several years before returning to the Jemez Mountains. As a result of that long ago contact, there are still strong ties between the Jemez and their cousins on Navajo territory at Jeddito. On their return to the Jemez Mountains, the people built the pueblo they now live in (Walatowa: The Place) and made peace with the Spanish authorities.

Some of the Jemez people had been making a type of plainware pottery (simple, undecorated, utilitarian) when they were still in the Four Corners area, while others had developed a distinctive type of black-on-white pottery. In moving to the Jemez Mountains, they brought their knowledge and techniques with them but had to adapt to the different materials available to work with. Over time, the Jemez got better in their agricultural practices and began trading agricultural goods to the people of Zia Pueblo in return for pottery. By the mid-1700s, the Jemez people were producing almost no pottery.

East of what is now Santa Fe is where the ruins of Cicuyé (Pecos) Pueblo are found. Cicuyé was a large pueblo housing up to 2,000 people at its height. The people of Cicuyé, and some in the northern Galisteo Basin, were the only other speakers of the Towa language in New Mexico. When that area fell on increasingly hard times (Apache and Comanche raids, European diseases, drought), Cicuyé was finally abandoned in 1838 when the last 17 residents moved to Jemez. The Governor of Jemez welcomed them and allowed them to retain many of their Cicuyé tribal offices (governorship and all). Descendants of former Cicuyé families still return to the site of their ancestral home every year to perform religious ceremonies in honor of their ancestors.

When general American interest in Puebloan pottery started to take off in the 1960s, the people of Jemez sought to recover that lost heritage. Today, the practice of traditional pottery-making is very much alive and well among the Jemez.

The focus of Jemez pottery today has mostly turned to the making of storytellers, nativities and other figures. Figures are an art form that now accounts for more than three-quarters of their pottery production.

Storytellers are usually grandparent figures with the figures of children attached to their bodies. The grandparents are pictured singing tribal songs and oral histories to their descendants. While this visual representation was first created at Cochiti Pueblo (a site in close geographical proximity to Jemez Pueblo) in the early 1960s by Helen Cordero, it speaks to the relationship between grandparents and grandchildren of every culture. Nativities, corn maidens, singing angels and many different animal forms are also popular among the potters of Jemez.

The pottery vessels made at Jemez Pueblo today are generally not black-on-white. Instead, the potters have adopted many colors, styles and techniques from other pueblos to the point where Jemez potters no longer have one distinct style of their own beyond that which stems naturally from the materials they themselves acquire from their surroundings: it doesn't matter what the shape or design is, the clay itself says uniquely "Jemez."

Jemez Pueblo at Wikipedia

Jemez Pueblo official website

Jemez Pueblo at the Catholic Encyclopedia

Pueblos of the Rio Grande, Daniel Gibson, ISBN-13:978-1-887896-26-0, Rio Nuevo Publishers, 2001

Prehistoric Hopi Pottery Designs, Jesse Walter Fewkes, ISBN-0-486-22959-9, Dover Publications, Inc., 1973

The Story of

the Wedding Vase

as told by Teresita Naranjo of Santa Clara Pueblo

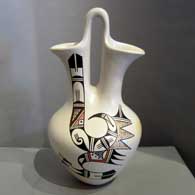

Helen Naha

Hopi

Wilma Baca Tosa

Jemez Pueblo

Margaret Tafoya

Santa Clara Pueblo

The Wedding Vase has been used for a long, long time in Indian Wedding Ceremonies.

After a period of courtship, when a boy and girl decide to get married, they cannot do so until certain customs have been observed. The boy must first call all his relatives together to tell them that he desires to be married to a certain girl. If the relatives agree, two or three of the oldest men are chosen to call on the parents of the girl. They pray according to Indian custom and the oldest man will tell the parents of the girl what their purpose is in visiting. The girl's parents never give a definite answer at this time, but just say that they will let the boy's family know their decision later.

About a week later, the girl calls a meeting of her relatives. The family then decides what answer should be given. If the answer is “no” that is the end of it. If the answer is “yes” then the oldest men in her family are delegated to go to the boy's home, and to give the answer, and to tell the boy on what day he can come to receive his bride-to-be. The boy must also notify all of his relatives on what day the girl will receive him, so that they will be able to have gifts for the girl.

Now the boy must find a Godmother and Godfather. The Godmother immediately starts making the wedding vase so that it will be finished by the time the girl is to be received. The Godmother also takes some of the stones which have been designated as holy and dips them into water, to make it holy water. It is with this holy water that the vase is filled on the day of the reception.

The reception day finally comes and the Godmother and Godfather lead the procession of the boy's relatives to the home of the girl. The groom is the last in line and must stand at the door of the bride's home until the gifts his relatives have brought have been opened and received by the bride.

The bride and groom now kneel in the middle of the room with the groom's relatives and the bride's parents praying all around them. The bride then gives her squash blossom necklace to the groom's oldest male relative, while the groom gives his necklace to the bride's oldest male relative. After each man has prayed, the groom's necklace is placed on the bride, and the bride's is likewise placed on the groom.

After the exchange of squash blossom necklaces and prayers, the Godmother places the wedding vase in front of the bride and groom. The bride drinks out of one side of the wedding vase and the groom drinks from the other. Then, the vase is passed to all in the room, with the women all drinking from the bride's side, and the men from the groom's.

After the ritual drinking of the holy water and the prayers, the bride's family feeds all the groom's relatives and a date is set for the church wedding. The wedding vase is now put aside until after the church wedding.

Once the church wedding ceremony has occurred, the wedding vase is filled with any drink the family may wish. Once again, all the family drinks in the traditional manner, with women drinking from one side, and men the other. Having served its ceremonial purpose, the wedding vase is given to the young newlyweds as a good luck piece.

Copyright © 1998-2025 by