Click or tap to see a larger version

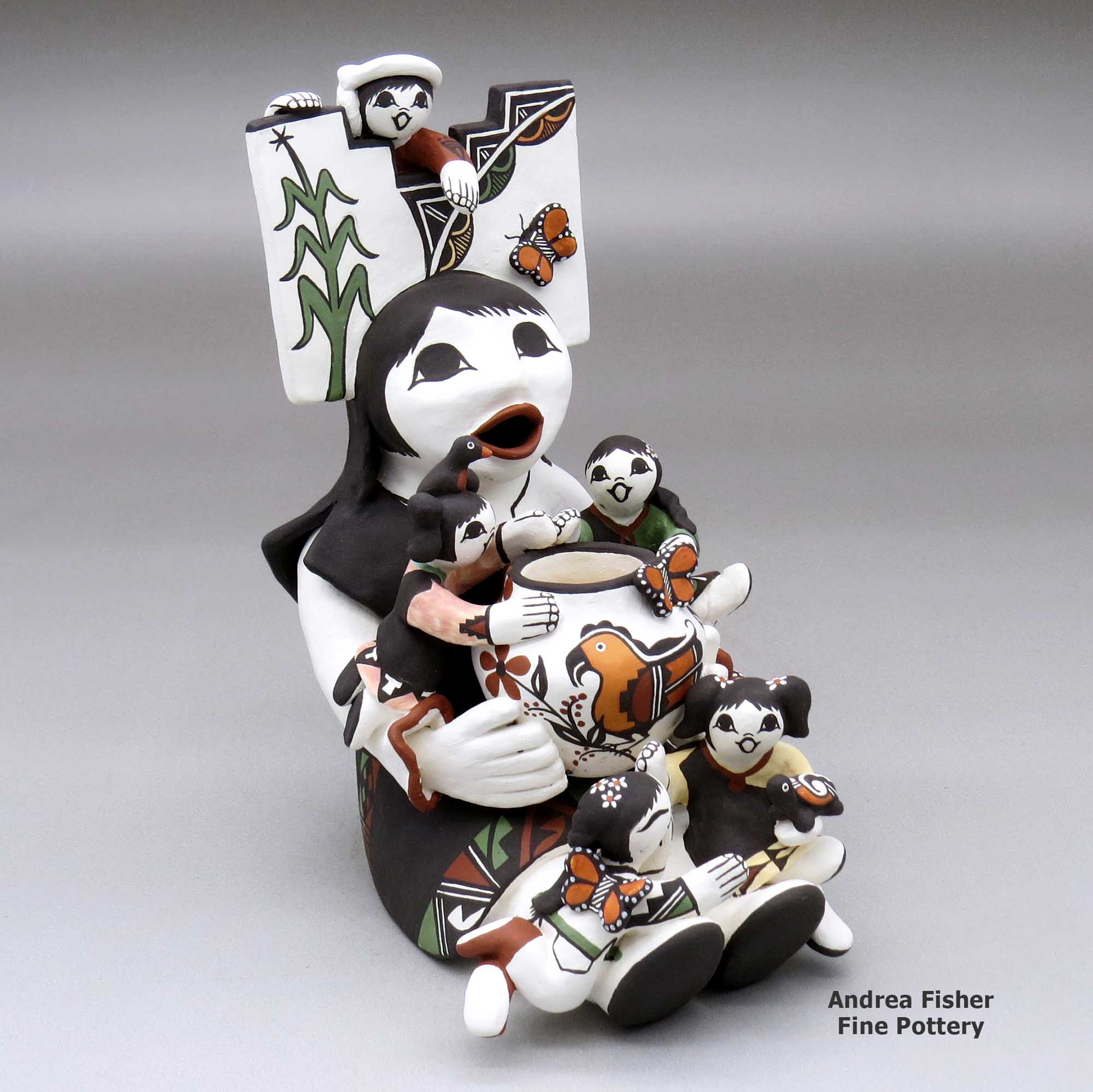

Marilyn Ray, Acoma, A sitting grandmother storyteller figure with a tablito on her head and with five children, butterflies, a turtle, a bird and a pot o n her

Acoma

$ 2500

zzac4j243

A sitting grandmother storyteller figure with a tablito on her head and with five children, butterflies, a turtle, a bird and a pot o n her

6 in L by 4.5 in W by 8.75 in H

Condition: Excellent

Signature: Marilyn Ray Acoma, NM

Date Created: 2024

Tell me more! Buy this piece!

(505) 986-1234 - www.andreafisherpottery.com - All Rights Reserved

Marilyn Ray

Acoma

Marilyn Lewis Ray was born to Edward and Kathryn Lewis of Acoma Pueblo in 1954. She is a member of one of the two non-related Lewis families at Acoma: the Lucy Lewis family of traditional potters is the more well known while the children of Kathryn Lewis (Rebecca Lucario, Marilyn Ray, Carolyn Concho, Diane Lewis and Judy Lewis) have been making some of the most innovative and contemporary pottery being produced at Acoma. Each member of the family has carved out their own particular niche and Marilyn has long been focused on the art of the storyteller.

In Native American pottery art, a storyteller refers to a figure, usually a grandparent, adorned with smaller figures of children. In Puebloan society, their histories are oral, to be sung in their native languages. The storyteller is an elder figure who sings the stories of their tribal culture to pass that knowledge on to the children. Helen Cordero of Cochiti Pueblo made the first storyteller in 1964 in honor of her grandfather, a great storyteller. The tradition soon spread to other pueblos, each potter adapting the dress and hairstyles to their own society but also each exhibiting a distinctive and delightful expression of the intense love the Pueblo people have for their children. Figures with an open mouth represent a grandparent or parent singing or telling stories to their children.

Marilyn's playful figures capture her deep sense of humor: some of the children are climbing, some playing with puppies, some just being mischievous. She says she was inspired to make pottery by her late grandmother, Dolores S. Sanchez, who encouraged her to make small animal figurines when she was twelve. Marilyn also sold her small pieces alongside those of her grandmother.

Her grandparents took her with them to help mine the clay. They taught her to use natural materials that were abundant to decorate her pieces. Most importantly, they taught her how to use the sacred earth to make a living. Marilyn's motivation intensified after her grandmother gave her a special polishing stone.

Years later, Marilyn grew bored with just black, orange and white, the basic colors for which Acoma potters are known. She began to experiment with colored clay slips and over the next four years discovered twelve new colors to use on her figures. She says she tries to work on figurines at least six hours a day but she also has to tend to her family: as she has told us many times, "I love to be home with my husband and Cinnamon Dog."

In addition to her storytellers, Marilyn likes to make Friendship/Corn Meal bowls (with butterflies, lady bugs and children hanging over the sides), Nativities, Singing Maidens, Corn Maidens and animals (including bear storytellers with cubs and turtles carrying children). Her sense of humor and love of life are evident in all her creations. Marilyn also puts time aside to work with other potters, both to inspire and to be inspired.

Marilyn's storytellers have become collectors items. They have been featured in several books and magazines including Douglas Congdon-Martin's book Storytellers and other Figurative Pottery. In January 1993, her work was even featured on an Albuquerque billboard.

Marilyn's art has earned her more than 300 prize ribbons, including many from The Heard Museum Show in Phoenix, the Santa Fe Indian Market, Eight Northern Pueblos Arts and Crafts Show and Gallup Inter-Tribal Ceremonials, among others. She signs her work: "Marilyn Ray, Acoma, NM" along with a date and a lizard hallmark.

Some Awards Earned by Marilyn

- 2010 Santa Fe Indian Market, Classification II - Pottery, Division D - Contemporary pottery, any form or design, using Native materials with or without added decorative elements, all firing techniques, Category 705 - Figures, including sets: Second Place

- 2009 Santa Fe Indian Market, Classification II - Pottery, Division D - Contemporary pottery, any form or design, using Native materials with or without added decorative elements, all firing techniques, Category 705 - Figures, including sets: First Place

- 2008 Santa Fe Indian Market, Classification II - Pottery, Division H - Non-traditional pottery, any form or design, using traditional materials with added non-clay decorative elements, all firing techniques, Category 1505 - Figures (set of two or more separate pieces): First Place

- 2005 Santa Fe Indian Market: Special Awards, Standards Award II, Pottery: New Innovation in Clay (Limited to Plates)

- 2004 Santa Fe Indian Market, Classification II - Pottery, Division G - Non-traditional pottery, using traditional techniques and materials, any form or design, Category 1407 - Items with figures or designs in relief: Second Place

- 2004 Santa Fe Indian Market, Classification II - Pottery, Division H - Non-traditional pottery using traditional materials and techniques with non-traditional decorative elements, Category 1505 - Figures (set of two or more separate pieces): First Place

- 2004 Santa Fe Indian Market, Classification II - Pottery, Division H - Non-traditional pottery using traditional materials and techniques with non-traditional decorative elements, Category 1508 - Miscellaneous: Second Place

- 2003 Santa Fe Indian Market, Classification II - Pottery, Division F - Traditional pottery, painted designs on matte or semi-matte surface, Category 1306 - Storytellers, all one piece: First Place

- 2003 Santa Fe Indian Market, Classification II - Pottery, Division G - Non-traditional pottery, using traditional materials and techniques, any form or design, Category 1411 - Miscellaneous: Second Place

- 2002 Santa Fe Indian Market, Classification II - Pottery, Division H - Non-traditional pottery using traditional materials and techniques with non-traditional decorative elements, any form or design, Category 1506 - Figures (sets of two or more pieces): Third Place

- 2002 Santa Fe Indian Market, Classification II - Pottery, Division J - Non-traditional pottery, all materials all techniques with or without decorative elements, any form or design, Category 1607 - Sets & Scenes (multi-figures, includes nativity scenes and storyteller bowls): Second Place

- 2001 Santa Fe Indian Market, Classification II - Pottery, Division G - Non-traditional pottery, new forms and designs, using traditional materials and all firing techniques, Category 1405 - Figures, sets of two or more pieces: Second Place

- 2000 Santa Fe Indian Market, Classification II - Pottery, Division H - Non-traditional pottery, any forms using non-traditional materials or techniques, Category 1510 - Single figures (animal & other), all other: Second Place

- 2000 Santa Fe Indian Market, Classification II - Pottery, Division H - Non-traditional pottery, any forms using non-traditional materials or techniques, Category 1511 - Sets & scenes (nativity scenes): Second Place

- 1999 Santa Fe Indian Market, Classification II - Pottery, Division H - Non-traditional any forms using non-traditional materials or techniques, Category 1513 - Storyteller (non-traditional), up to 7" in height: Second Place

- 1998 Santa Fe Indian Market, Classification II - Pottery, Division F - Traditional pottery, painted designs on matte or semi-matte surface, all forms except jars, Category 1310 - Storytellers (all one piece), other than Cochiti: Third Place

- 1998 Santa Fe Indian Market, Classification II - Pottery, Division G - Non-traditional pottery, new forms, using traditional materials and techniques, Category 1407 - Figures (all one piece), over 7": Third Place

- 1997 Santa Fe Indian Market, Classification II - Pottery, Division F - Traditional pottery, painted designs on matte or semi-matte surface, all forms except jars, Category 1310 - Storytellers (all one piece): First Place

- 1997 Santa Fe Indian Market, Classification II - Pottery, Division F - Traditional pottery, painted designs on matte or semi-matte surface, all forms except jars, Category 1310 - Storytellers (all one piece): Third Place

- 1997 Santa Fe Indian Market, Classification II - Pottery, Division H - Non-traditional any forms using non-traditional materials or techniques, Category 1513 - Storyteller (non-traditional), up to 7" in height: Second Place

- 1997 14th Annual Phoenix Indian Center Bola Dinner and Awards Banquet: Collector's Choice Artist

- 1996 Santa Fe Indian Market, Classification II - Pottery, Division H - Non-traditional any forms using non-traditional materials or techniques, Category 1510 - Single figures (animal & others): Third Place

- 1996 Santa Fe Indian Market, Classification II - Pottery, Division H - Non-traditional any forms using non-traditional materials or techniques, Category 1513 - Storyteller (non-traditional) up to 7" in height: First Place

- 1996 Santa Fe Indian Market, Classification II - Pottery, Division J - Traditional forms, jars, melon bowls, seed bowls, black, Category 1609 - Non-traditional forms: First Place

- 1994 Santa Fe Indian Market, Classification II - Pottery, Division G - Traditional pottery, painted designs on matte or semi-matte surface, all forms except jars, Category 1410 - Storytellers (all one place): First Place

- 1994 Santa Fe Indian Market, Classification II - Pottery, Division G - Traditional pottery, painted designs on matte or semi-matte surface, all forms except jars, Category 1411 - Nativity scenes: Third Place

- 1994 Santa Fe Indian Market, Classification II - Pottery, Division H - Non-traditional, new forms, using traditional materials & techniques, Category 1506 - Figures (all one piece): First Place

- 1994 Santa Fe Indian Market, Classification II - Pottery, Division H - Non-traditional, new forms, using traditional materials & techniques, Category 1507 - Figures (sets of two or more pieces): Third Place

- 1994 Santa Fe Indian Market, Classification II - Pottery, Division H - Non-traditional, new forms, using traditional materials & techniques, Category 1509 - Miscellaneous, over 7": Second Place

- 1989 Santa Fe Indian Market, Classification II - Pottery, Division K - Pottery Miniatures, 3" or less in height or diameter, Category 1509 - Figures, sets of two or more figures: Third Place

- 1983 Santa Fe Indian Market, Classification II - Pottery, Division F - Traditional, painted designs on matte or semi-matte surface: Third Place

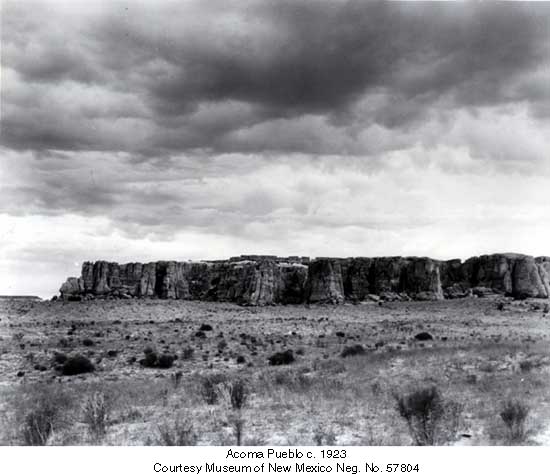

Acoma Pueblo

Sky City

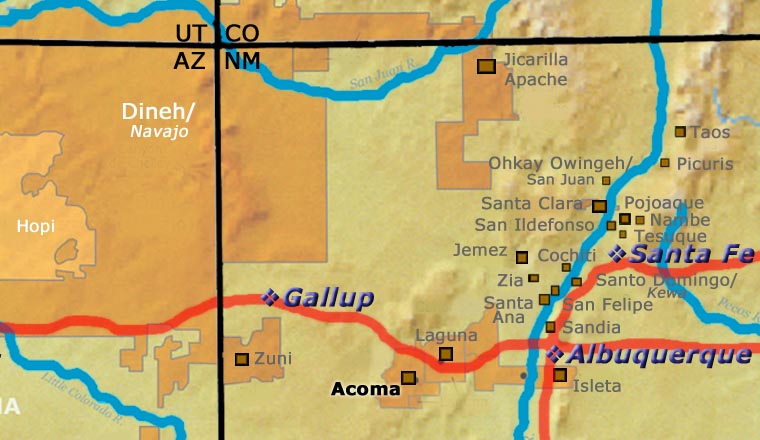

According to Acoma oral history, the sacred twins led their ancestors to "Aaku," a magical mesa composed mostly of white rock, and instructed those ancestors to make that mesa their home. Acoma Pueblo is called "Sky City" because of its position atop the mesa. Acoma is located about 60 miles west of Albuquerque.

According to some archaeologists, a large group of Keres-speaking people left the Chaco Canyon area in the late 900s. They headed south, around the west side of the Mount Taylor volcano and across the Rio San Jose to Aaku, where they merged into a pueblo of people already living there.

Acoma, Old Oraibi (at Hopi) and Taos all lay claim to being the oldest continuously inhabited community in the U.S. Those competing claims are hard to settle as each village can point to archaeological remnants close by to substantiate each village's claim. While the people of Acoma have an oral tradition that says they've been living in the same area for more than 2,000 years, some archaeologists feel more that the present pueblo was established near the end of the major migrations of the 1200s and 1300s. The location is essentially on the boundary between the Mimbres-Mogollon to the south and west, and Ancestral Puebloan cultures to the north and east. Each of those cultures has had an impact on the styles and designs of Acoma pottery, especially since modern potters have been getting the inspiration for many of their designs from ancient potsherds they have found while walking on pueblo lands.

Francisco Vasquez de Coronado ascended the cliff to visit the Acomas in 1540. He afterward wrote that he "repented having gone up to the place." But the Spanish came back again, and kept coming back. In 1598 relations between the Spanish and the Acomas took a really bad turn with the arrival of Don Juan de Oñaté and the soldiers, settlers and Franciscan monks that accompanied him. After ascending to the mesa top, Oñaté decided to force the Acomas to swear loyalty to the King of Spain and to the Pope. When the Acomas realized what the Spanish meant by that, a group of Acoma warriors attacked a group of Spanish soldiers and killed 11 of them, including one of Oñaté's nephews.

Don Juan de Oñaté retaliated by attacking the pueblo, burning most of it and killing more than 600 people. Another 500 people were imprisoned by the Spanish: males between the ages of 12 and 25 were sold into slavery and 24 men over the age of 25 had their right foot amputated. Many of the women over the age of 12 were also forced into slavery and were eventually parceled out among Catholic convents in Mexico City. Two Hopi men also captured at Acoma had one hand cut off. Then they were released and sent home to spread the word about Spain's resolve to subjugate the inhabitants of Nuevo Mexico.

When word of the massacre and the punishments meted out got back to King Philip in Spain, he banished Don Juan de Oñaté from Nuevo Mexico. Some Acomas had escaped that fateful Spanish attack and returned to the mesa top in 1599 to begin rebuilding. In 1620 a Royal Decree was issued establishing civil offices in each pueblo, and Acoma had its first governor appointed. Those governors met at Santo Domingo Pueblo at the All Pueblos Council, the first democratic institution in the Americas, an institution that is still functioning.

By 1680, the situation between the pueblos and the Spanish had deteriorated to the point where the Acomas were extremely willing participants in the 1680 Pueblo Revolt. After the successful Pueblo Revolt, the Spanish retreated to Mexico. Refugees from other pueblos began arriving at Acoma, fearing an eventual Spanish return and reprisals. That strained the resources of Acoma until the Spanish actually did return. Then residents of the pueblo had to make a difficult decision. Many of the refugees chose to try a peaceful solution: they relocated to the ancient Laguna area and made peace with the Spanish as soon as they appeared in the region. Acoma made peace with the Spanish soon after.

Over the next 200 years, Acoma suffered from outbreaks of smallpox and other European-introduced diseases to which they had no natural immunity. They also sided with the Spanish against raiders from the Navajo and Apache tribes. Then New Mexico changed hands a couple times, the railroads arrived and, like every other Native American pueblo, the Acoma people became dependent on inexpensive goods brought in from the outside world.

For many years the villagers were content on the mesa top and they kept advances in technology below. Now most live in villages on the valley floor where water, electricity, natural gas and other "luxuries" are easily available. While a few families still make their permanent home on the mesa top, the old pueblo is used almost exclusively for ceremonies and celebrations these days.

Historically, Acoma was known for large, thin-walled "ollas," jars used for storing food and water. With the arrival of the railroad and tourists in the 1880s, Acoma potters adapted the size, shapes and styles of their pots in order to appeal to the new buyers.

Up into the mid-1960s, most Acoma potters felt it was an inappropriate display of ego to sign their pots. Then Kenneth Chapman convinced Lucy Lewis, Jessie Garcia and Marie Z. Chino of the value of their signatures and they started signing their pieces. The 1960s is also a time when the primary Acoma white clay vein passed through a layer of widely distributed impurities, impurities that passed through the clay filtering process and showed up only during and after the firing. The problem was so bad it affected virtually every Acoma potter and every pot they made. Thankfully, by the late 1960s they had burrowed through that layer of clay and into a deeper layer that didn't have the problem.

Acoma Pueblo at Wikipedia

Pueblo of Acoma official website

Pueblos of the Rio Grande, Daniel Gibson, ISBN-13:978-1-887896-26-9, Rio Nuevo Publishers, 2001

Upper photo courtesy of Marshall Henrie, Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 3.0 Unported License

Storytellers

Pueblos: Cochiti, Jemez, Acoma, Isleta, Santa Clara

Helen Cordero

Cochiti Pueblo

Judy Toya

Jemez Pueblo

Marilyn Ray

Acoma Pueblo

Clay figurines have been present in the Pueblo pottery tradition for at least the last thousand years. However, between 1540 and 1820 CE, figures and effigies were denounced as "works of the devil" by the Spanish priests. Before and after that time, the art of making figurative pottery flourished, especially at Cochiti Pueblo.

The "storyteller" is an important role in the tribe as the Native American people did not have a method for writing down anything. The closest thing they had to a written language were the designs they used to decorate pottery, textiles, baskets and stone. The storyteller's role was to preserve, retell and pass down the oral history of their people. In most tribes that role was fulfilled by men.

The first real storyteller figure was created in 1964 by Cochiti Pueblo potter Helen Cordero. She made it in memory of her grandfather, Santiago Quintana, and the stories he sang to her and other children in their native Keres when she was young. Helen's creation struck a chord throughout all the pueblos as the storyteller is a figure central to all their societies. Most tribes also have the figure of the Singing Maiden in their pantheon and in many cases, the mix of Singing Maiden and Storyteller has blurred some lines in the pottery world. Today, as many as three hundred potters in thirteen pueblos have created storytellers, and their storytellers are not only men and women but also Santa's, mudheads, koshares, bears, owls and other animals, sometimes encumbered with children numbering more than one hundred! Each potter has also customized their storyteller figures to more closely reflect the forms, dress and decorations of their own tribes, often even of their own clans.

Delores Sanchez Family Tree

Disclaimer: This "family tree" is a best effort on our part to determine who the potters are in this family and arrange them in a generational order. The general information available is questionable so we have tried to show each of these diagrams to living members of each family to get their input and approval, too. This diagram is subject to change should we get better info.

- Delores Sandoval Sanchez (ca. 1888-1991) & Toribio Sanchez

- Marie S. Juanico (1937-2024)

- Delores Aragon (Juanico) (1969-)

- Katherine Lewis (1932-)

- Bernard Lewis (1957-) & Sharon Lewis (1959-)

- Eric Lewis (1978-)

- Carolyn Concho (1961-) & George Concho, Sr.

- Alisha Sanchez & Greg Concho

- Shaylene Chino & George Concho Jr.

- Alisha Sanchez & Greg Concho

- Diane Lewis (1959-)

- Judy Lewis (1966-)

- Rebecca Lucario(1951-)

- Amanda Lucario (1984-)

- Daniel Lucario (1969-)

- Marilyn Ray (1954-)

- Edward Lewis Jr. & Eva Concho

- Edward Lewis III

- Bernard Lewis (1957-) & Sharon Lewis (1959-)

- Ethel Shields (1926-) & Don Shields

- Charmae Shields Natseway (1958-) & Thomas Natseway (1953-)(Laguna)

- Chris Shields & Michelle Shields (1972-)

- Curtis Shields

- Isaac Shields

- Natasha Shields

- Jack Shields (c.1961-)

- Judy Shields (daughter-in-law)

- Verda Mae Shields (daughter-in-law)

Some of the above info is drawn from Southern Pueblo Pottery, 2000 Artist Biographies, by Gregory Schaaf, © 2002, Center for Indigenous Arts & Studies

Other info is derived from personal contacts with family members and through interminable searches of the Internet and cross-examination of the data found.

Copyright © 1998-2025 by