Click or tap to see a larger version

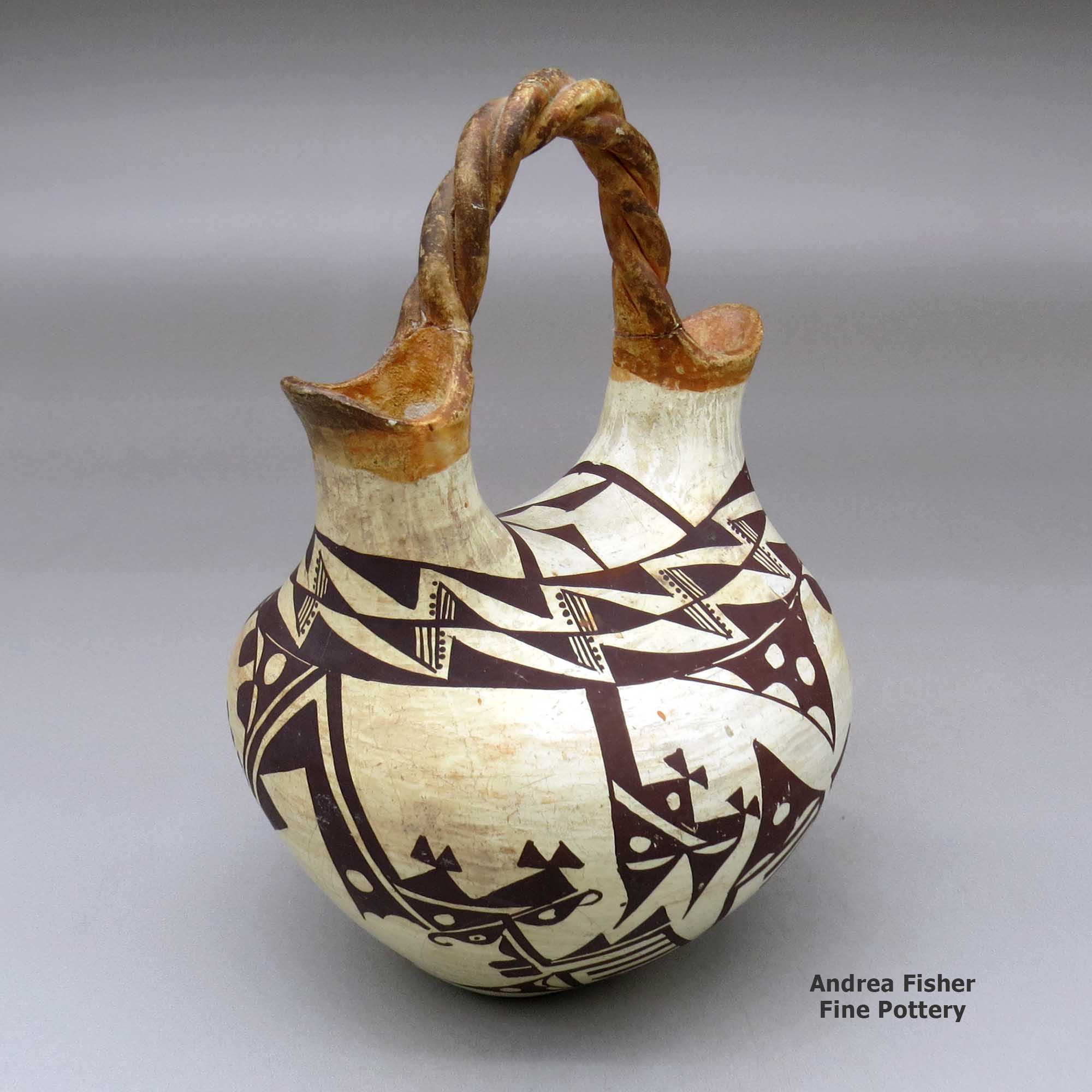

Unknown, Acoma, A polychrome wedding vase with a twisted bridge and decorated with a two-panel geometric design

Acoma

$ 525

rbac4j105

A polychrome wedding vase with a twisted bridge and decorated with a two-panel geometric design

6 in L by 6.5 in W by 8.75 in H

Condition: Good for its age with some restoration, see image 2

Signature: Acoma N.M

Tell me more! Buy this piece!

(505) 986-1234 - www.andreafisherpottery.com - All Rights Reserved

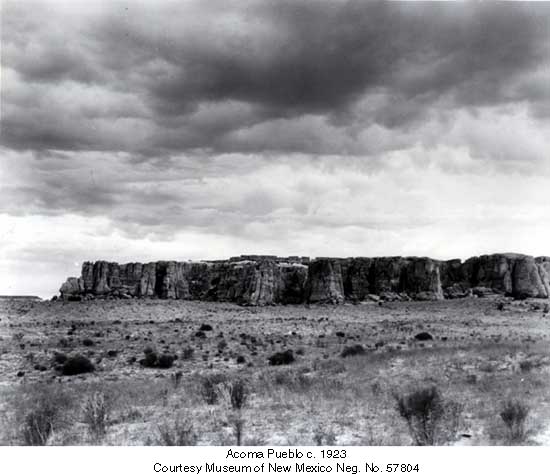

Acoma Pueblo

Sky City

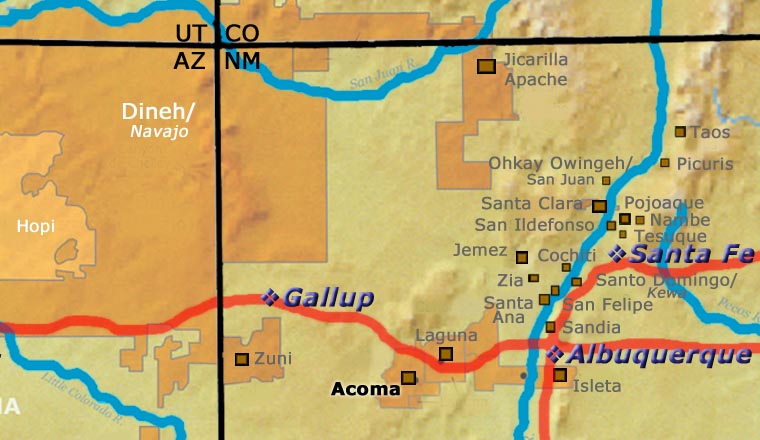

According to Acoma oral history, the sacred twins led their ancestors to "Aaku," a magical mesa composed mostly of white rock, and instructed those ancestors to make that mesa their home. Acoma Pueblo is called "Sky City" because of its position atop the mesa. Acoma is located about 60 miles west of Albuquerque.

According to some archaeologists, a large group of Keres-speaking people left the Chaco Canyon area in the late 900s. They headed south, around the west side of the Mount Taylor volcano and across the Rio San Jose to Aaku, where they merged into a pueblo of people already living there.

Acoma, Old Oraibi (at Hopi) and Taos all lay claim to being the oldest continuously inhabited community in the U.S. Those competing claims are hard to settle as each village can point to archaeological remnants close by to substantiate each village's claim. While the people of Acoma have an oral tradition that says they've been living in the same area for more than 2,000 years, some archaeologists feel more that the present pueblo was established near the end of the major migrations of the 1200s and 1300s. The location is essentially on the boundary between the Mimbres-Mogollon to the south and west, and Ancestral Puebloan cultures to the north and east. Each of those cultures has had an impact on the styles and designs of Acoma pottery, especially since modern potters have been getting the inspiration for many of their designs from ancient potsherds they have found while walking on pueblo lands.

Francisco Vasquez de Coronado ascended the cliff to visit the Acomas in 1540. He afterward wrote that he "repented having gone up to the place." But the Spanish came back again, and kept coming back. In 1598 relations between the Spanish and the Acomas took a really bad turn with the arrival of Don Juan de Oñaté and the soldiers, settlers and Franciscan monks that accompanied him. After ascending to the mesa top, Oñaté decided to force the Acomas to swear loyalty to the King of Spain and to the Pope. When the Acomas realized what the Spanish meant by that, a group of Acoma warriors attacked a group of Spanish soldiers and killed 11 of them, including one of Oñaté's nephews.

Don Juan de Oñaté retaliated by attacking the pueblo, burning most of it and killing more than 600 people. Another 500 people were imprisoned by the Spanish: males between the ages of 12 and 25 were sold into slavery and 24 men over the age of 25 had their right foot amputated. Many of the women over the age of 12 were also forced into slavery and were eventually parceled out among Catholic convents in Mexico City. Two Hopi men also captured at Acoma had one hand cut off. Then they were released and sent home to spread the word about Spain's resolve to subjugate the inhabitants of Nuevo Mexico.

When word of the massacre and the punishments meted out got back to King Philip in Spain, he banished Don Juan de Oñaté from Nuevo Mexico. Some Acomas had escaped that fateful Spanish attack and returned to the mesa top in 1599 to begin rebuilding. In 1620 a Royal Decree was issued establishing civil offices in each pueblo, and Acoma had its first governor appointed. Those governors met at Santo Domingo Pueblo at the All Pueblos Council, the first democratic institution in the Americas, an institution that is still functioning.

By 1680, the situation between the pueblos and the Spanish had deteriorated to the point where the Acomas were extremely willing participants in the 1680 Pueblo Revolt. After the successful Pueblo Revolt, the Spanish retreated to Mexico. Refugees from other pueblos began arriving at Acoma, fearing an eventual Spanish return and reprisals. That strained the resources of Acoma until the Spanish actually did return. Then residents of the pueblo had to make a difficult decision. Many of the refugees chose to try a peaceful solution: they relocated to the ancient Laguna area and made peace with the Spanish as soon as they appeared in the region. Acoma made peace with the Spanish soon after.

Over the next 200 years, Acoma suffered from outbreaks of smallpox and other European-introduced diseases to which they had no natural immunity. They also sided with the Spanish against raiders from the Navajo and Apache tribes. Then New Mexico changed hands a couple times, the railroads arrived and, like every other Native American pueblo, the Acoma people became dependent on inexpensive goods brought in from the outside world.

For many years the villagers were content on the mesa top and they kept advances in technology below. Now most live in villages on the valley floor where water, electricity, natural gas and other "luxuries" are easily available. While a few families still make their permanent home on the mesa top, the old pueblo is used almost exclusively for ceremonies and celebrations these days.

Historically, Acoma was known for large, thin-walled "ollas," jars used for storing food and water. With the arrival of the railroad and tourists in the 1880s, Acoma potters adapted the size, shapes and styles of their pots in order to appeal to the new buyers.

Up into the mid-1960s, most Acoma potters felt it was an inappropriate display of ego to sign their pots. Then Kenneth Chapman convinced Lucy Lewis, Jessie Garcia and Marie Z. Chino of the value of their signatures and they started signing their pieces. The 1960s is also a time when the primary Acoma white clay vein passed through a layer of widely distributed impurities, impurities that passed through the clay filtering process and showed up only during and after the firing. The problem was so bad it affected virtually every Acoma potter and every pot they made. Thankfully, by the late 1960s they had burrowed through that layer of clay and into a deeper layer that didn't have the problem.

Acoma Pueblo at Wikipedia

Pueblo of Acoma official website

Pueblos of the Rio Grande, Daniel Gibson, ISBN-13:978-1-887896-26-9, Rio Nuevo Publishers, 2001

Upper photo courtesy of Marshall Henrie, Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 3.0 Unported License

The Story of

the Wedding Vase

as told by Teresita Naranjo of Santa Clara Pueblo

Helen Naha

Hopi

Wilma Baca Tosa

Jemez Pueblo

Margaret Tafoya

Santa Clara Pueblo

The Wedding Vase has been used for a long, long time in Indian Wedding Ceremonies.

After a period of courtship, when a boy and girl decide to get married, they cannot do so until certain customs have been observed. The boy must first call all his relatives together to tell them that he desires to be married to a certain girl. If the relatives agree, two or three of the oldest men are chosen to call on the parents of the girl. They pray according to Indian custom and the oldest man will tell the parents of the girl what their purpose is in visiting. The girl's parents never give a definite answer at this time, but just say that they will let the boy's family know their decision later.

About a week later, the girl calls a meeting of her relatives. The family then decides what answer should be given. If the answer is “no” that is the end of it. If the answer is “yes” then the oldest men in her family are delegated to go to the boy's home, and to give the answer, and to tell the boy on what day he can come to receive his bride-to-be. The boy must also notify all of his relatives on what day the girl will receive him, so that they will be able to have gifts for the girl.

Now the boy must find a Godmother and Godfather. The Godmother immediately starts making the wedding vase so that it will be finished by the time the girl is to be received. The Godmother also takes some of the stones which have been designated as holy and dips them into water, to make it holy water. It is with this holy water that the vase is filled on the day of the reception.

The reception day finally comes and the Godmother and Godfather lead the procession of the boy's relatives to the home of the girl. The groom is the last in line and must stand at the door of the bride's home until the gifts his relatives have brought have been opened and received by the bride.

The bride and groom now kneel in the middle of the room with the groom's relatives and the bride's parents praying all around them. The bride then gives her squash blossom necklace to the groom's oldest male relative, while the groom gives his necklace to the bride's oldest male relative. After each man has prayed, the groom's necklace is placed on the bride, and the bride's is likewise placed on the groom.

After the exchange of squash blossom necklaces and prayers, the Godmother places the wedding vase in front of the bride and groom. The bride drinks out of one side of the wedding vase and the groom drinks from the other. Then, the vase is passed to all in the room, with the women all drinking from the bride's side, and the men from the groom's.

After the ritual drinking of the holy water and the prayers, the bride's family feeds all the groom's relatives and a date is set for the church wedding. The wedding vase is now put aside until after the church wedding.

Once the church wedding ceremony has occurred, the wedding vase is filled with any drink the family may wish. Once again, all the family drinks in the traditional manner, with women drinking from one side, and men the other. Having served its ceremonial purpose, the wedding vase is given to the young newlyweds as a good luck piece.

Copyright © 1998-2025 by