Click or tap to see a larger version

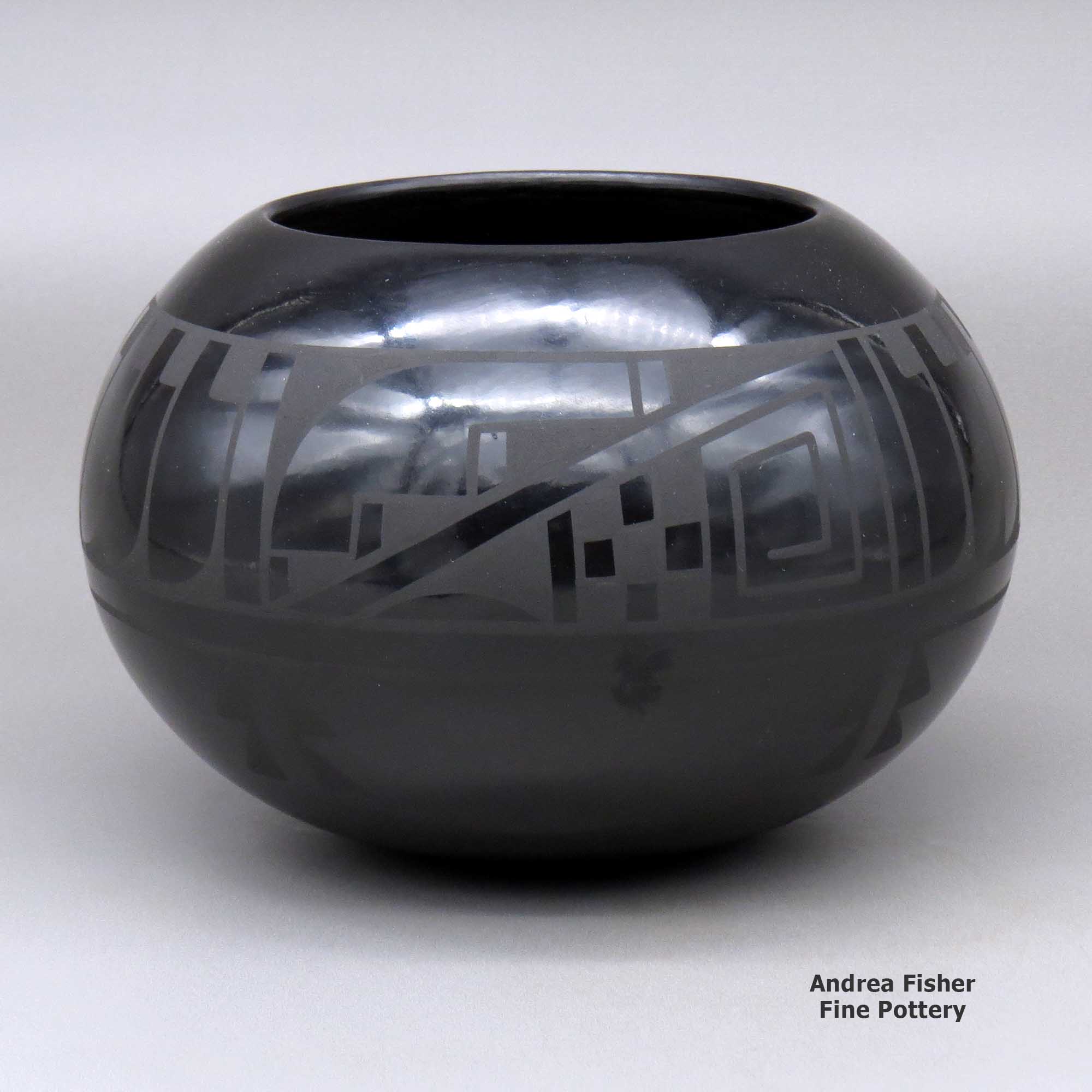

Erik Fender, San Ildefonso, A black on black bowl decorated with a band of feather and geometric design around and above the shoulder

San Ildefonso

$ 1150

dksi4j034

A black on black bowl decorated with a band of feather and geometric design around and above the shoulder

7 in L by 7 in W by 4.75 in H

Condition: Very good

Signature: Than Tsideh

Tell me more! Buy this piece!

(505) 986-1234 - www.andreafisherpottery.com - All Rights Reserved

Erik Fender

San Ildefonso

Erik Fender was born in 1970. His mother is Martha Appleleaf, his grandmother Carmelita Dunlap. Johnnie Tse-Pe was his uncle.

As a boy, Erik learned about working with clay by watching his mother, his grandmother and his uncle, Carlos Sunrise Dunlap, making pottery. He couldn't keep his hands out of the clay and learned quickly. He was earning blue ribbons for his painting and for his pottery before he was 18. Sometimes his mother had him paint pots for her.

Erik developed an innovative black-on-red style where he separates bands of painted design with bands of low-relief sgraffito design. He also makes green-on-black and polychrome pots.

Erik told us he's inspired by historic pieces of San Ildefonso pottery. He feels the spirit in it and wants to keep that spirit alive in his pueblo. So in addition to creating San Ildefonso Revival styles of his own, he teaches classes in making pottery and jewelry at the Poeh Cultural Center at Pojoaque Pueblo. That's where he gets his fun: hanging out with his students and sharing insights about Tewa culture and history.

Erik says he's drawn from designs of the past to help create his own. His pots speak for themselves, and that's the kind of legacy he wants. He signs most of his pieces Than Tsideh, meaning: Sunbird.

Some Awards Erik has Won

- 2024 Santa Fe Indian Market, Classification IIC: Category 705 - Painted designs on a black or red burnished surface, any form, in the style of San Ildefonso, First Place and Honorable Mention

- 2024 Santa Fe Indian Market, Classification IIB: Category 603 - Painted polychrome pottery in the style of Cochiti, Santo Domingo, Santa Clara, San Ildefonso, Tesuque, Nambe, San Juan, Pojoaque, any form, Honorable Mention

- 2023 Santa Fe Indian Market, Pottery Classification II C: Category 705 - Painted designs on a black or red burnished or polished surface, any form in the style of San Ildefonso: First Place

- 2020 Heard Museum Guild Indian Fair & Market, Classification II - Pottery, Division A- Painted, native clay, hand built, fired out-of-doors: First Place. Awarded for artwork: Black-on-Black Jar

- 2019 Santa Fe Indian Market, Classification II - Pottery, Division C - Traditional Burnished Black or Red Ware; Incised, Painted or Carved, Category 705 - Painted designs on a black or red burnished or polished surface, any form in the style of Ildefonso: First Place

- 2019 Santa Fe Indian Market, Classification II - Pottery, Division D - Contemporary pottery, any form or design, using Native materials with or without added decorative elements, traditional firing techniques, Category 806 - With added elements (like beads, feathers, stone, etc.): First Place

- 2019 Heard Museum Guild Indian Fair & Market, Classification II - Pottery, Division E - Any design or form with native materials, kiln fired pottery: Second Place. Awarded for artwork: "Dragonfly Vase"

- 2018 Santa Fe Indian Market, Classification II - Pottery, Division B - Traditional Painted Pottery, Category 603 - Painted Polychrome Pottery in the Style of Cochiti, Santo Domingo, Santa Clara, San Ildefonso, Tesuque, Nambe, San Juan, Pojoaque, Any Form: Honorable Mention

- 2018 Santa Fe Indian Market, Classification II - Pottery, Division C - Traditional Burnished Black or Red Ware; Incised, Painted or Carved, Category 705 - Painted designs on a black or red burnished or polished surface, any form in the style of Ildefonso: First Place

- 2018 Santa Fe Indian Market, Classification II - Pottery, Division C - Traditional Burnished Black or Red Ware; Incised, Painted or Carved, Category 705 - Painted designs on a black or red burnished or polished surface, any form in the style of Ildefonso: Honorable Mention

- 2017 Santa Fe Indian Market, Classification II - Pottery, Division B - Traditional: Best of Division

- 2017 Santa Fe Indian Market, Classification II - Pottery, Division B - Traditional, Category 603 - Painted polychrome pottery in the style of Cochiti, Santo Domingo, Santa Clara, San Ildefonso, Tesuque, Nambe, San Juan, Pojoaque, any form: First Place

- 2017 Santa Fe Indian Market, Classification II - Pottery, Division D - Contemporary Pottery, any form or design, using Native materials with or without added decorative elements, traditional firing techniques, Category 806 - With added elements (like beads, feathers, stones, etc), any form: Second Place

- 2017 Heard Museum Guild Indian Fair & Market, Classification II - Pottery, Division A - Painted, Native Clay, Hand Built, Fired Out-of-Doors: Second Place. Awarded for Art Work: Black-on-Black Jar

- 2014 Heard Museum Guild Indian Fair & Market, Classification II - Pottery, Division A - Traditional, native clay, hand built, painted: Second Place

- 2013 Heard Museum Guild Indian Fair & Market, Classification II - Pottery, Division A - Traditional, native clay, hand built, painted: Honorable Mention

- 2012 Heard Museum Guild Indian Fair & Market, Classification II - Pottery, Division A - Traditional, native clay, hand built, painted: Second Place

- 2010 Heard Museum Guild Indian Fair & Market, Classification II - Pottery, Division A - Traditional, native clay, hand built, painted: Honorable Mention

- 2009 Heard Museum Guild Indian Fair & Market, Classification II - Pottery, Division A - Traditional, native clay, hand built, painted: Second Place

- 2008 Heard Museum Guild Indian Fair & Market, Classification II - Pottery, Division A - Traditional, native clay, hand built, painted: Honorable Mention

- 2008 Heard Museum Guild Indian Fair & Market, Classification II - Pottery, Division D - Traditional native clay, hand built, figurative: Second Place

- 2005 Heard Museum Guild Indian Fair & Market, Classification II - Pottery, Division A - Traditional, native clay, hand built, painted: Honorable Mention

- 2004 Santa Fe Indian Market, Classification II - Pottery, Division D - Traditional pottery, painted designs on burnished black or red surface: Best of Division

- 2004 Santa Fe Indian Market, Classification II - Pottery, Division D - Traditional pottery, painted designs on burnished black or red surface, Category 1101 - Jars, wedding jars: First Place

- 2001 Santa Fe Indian Market, Classification II - Pottery, Division D - Traditional pottery, painted designs on burnished black or red surface (in the style of Santa Clara or San Ildefonso): Best of Division shared with Martha Fender

- 2001 Santa Fe Indian Market, Classification II - Pottery, Division D - Traditional pottery, painted designs on burnished black or red surface (in the style of Santa Clara or San Ildefonso), Category 1103 - Bowls and jars with handles: Second Place

- 2001 Santa Fe Indian Market, Classification II - Pottery, Division D - Traditional pottery, painted designs on burnished black or red surface (in the style of Santa Clara or San Ildefonso), Category 1101 - Jars: First Place shared with Martha Fender

- 1998 Santa Fe Indian Market, Classification II - Pottery, Division D - Traditional pottery, Category 1101- Jars: Honorable Mention

- 1997 Santa Fe Indian Market, Classification II - Pottery, Division C - Traditional pottery, Category 1103 - Bowls: Second Place

San Ildefonso Pueblo

Black Mesa at San Ildefonso Pueblo

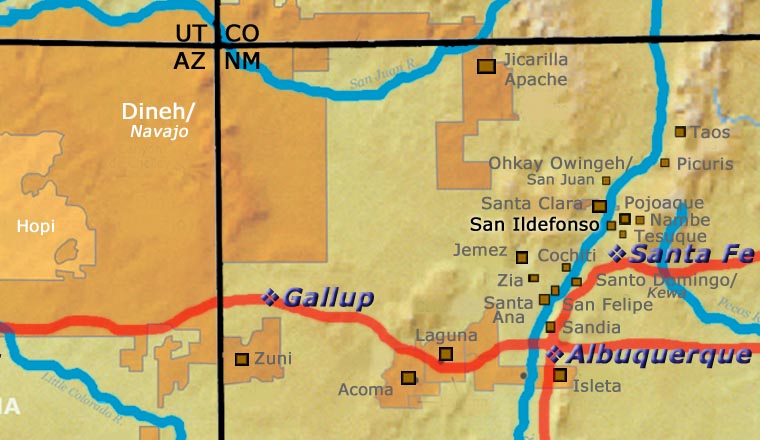

San Ildefonso Pueblo is located about twenty miles northwest of Santa Fe, New Mexico, west of Pojoaque, south of Santa Clara and straddling the Rio Grande. Although their ancestry has been traced to prehistoric pueblos in the Greater Mesa Verde area, the prehistoric pueblo at Tsankawi, in a non-contiguous parcel of Bandelier National Monument, is their most recent ancestral home. Tsankawi abuts the reservation on its northwest side.

Franciscan monks named the village after San Ildefonso and in 1617, forced the tribe to build a mission church on top of the village's main kiva. Before that the village was known as Powhoge, "where the water cuts through" (in Tewa). Today's pueblo was established as long ago as the 1300s. When the Spanish arrived in 1540, they estimated the village population at about 2,000.

That mission was destroyed during the Pueblo Revolt of 1680 and when Don Diego de Vargas returned to reclaim San Ildefonso in 1694, he found virtually all the Tewa people camped out on top of nearby Black Mesa. After an extended siege the two sides negotiated a treaty and the people returned to their villages. However, the next 250 years were not so good for them.

The swine flu pandemic of 1918 reduced the pueblo's population to about 90. Their population has grown to more than 600 since but the only economic activity available on the pueblo itself involves creating art in one form or another. The only other work is off-pueblo. San Ildefonso's population is small compared to neighboring Santa Clara Pueblo, but the pueblo maintains its own religious traditions and ceremonial feast days.

San Ildefonso is most known for being the home of the most famous Pueblo Indian potter, Maria Martinez. Many other excellent potters from this pueblo have produced quality pottery, too, among them: Blue Corn, Tonita and Juan Roybal, Dora Tse Pe and Rose Gonzales. Of course, the descendants of Maria Martinez are still important pillars of San Ildefonso's pottery tradition. Maria's influence reached far and wide, so far and wide that even Juan Quezada of the Mata Ortiz pottery renaissance in Chihuahua, Mexico, came to San Ildefonso to learn from her.

San Ildefonso Pueblo at Wikipedia

Pueblo of San Ildefonso official website

Pueblos of the Rio Grande, by Daniel Gibson

Photo is in the public domain

Maria Martinez Family Tree

Disclaimer: This "family tree" is a best effort on our part to determine who the potters are in this family and arrange them in a generational order. The general information available is questionable so we have tried to show each of these diagrams to living members of each family to get their input and approval, too. This diagram is subject to change should we get better info.

- Cipriana Peña (c. 1810-)

- Santana Peña (1846-) & Antonio Domingo Peña (1841-)

- Nicolasa Peña Montoya (1863-1904) & Juan Cruz Montoya

- Tonita Martinez Roybal (1892-1945) & Alfredo Montoya

- Isabel Montoya (1898-1996) & Benjamin Atencio

- Angelita Atencio Sanchez (1927-1993) & Santiago Sanchez

- Sandra Sanchez Chaparro

- Gilbert Atencio (1930-1995)

- Tony Atencio (1928-)

- Helen Gutierrez (1935-1993) & Frank Gutierrez (Santa Clara)

- Carol & James Gutierrez

- Kathy Gutierrez Naranjo & Ernest J. Naranjo

- Rose Gutierrez

- Geraldine Gutierrez Shije (1959-)

- Angelita Atencio Sanchez (1927-1993) & Santiago Sanchez

- Rayita Montoya

- Santana Montoya & Antonio Vigil

- Lupita Vigil Martinez (1918-2006) & Anselmo Martinez (1909-1965)

- Reyes Peña (d. 1909) & Tomas Montoya (d. 1914)

- Desideria Montoya (1889-1982)

- Maria Montoya Martinez (1887-1980) & Julian Martinez (1884-1943)

- Adam Martinez (1903-2000) and Santana Roybal Martinez (1909-2002)

- George Martinez (1943-) & Pauline Martinez (Santa Clara)(1950-)

- Adam Martinez

- Jesse Martinez

- Jolene Martinez

- Anita Martinez (d. 1992) & Pino Martinez

- Barbara Tahn-Moo-Whe Gonzales (1947-) & Robert Gonzales

- Aaron Gonzales (1971-)

- Brandon Gonzales (1983-)

- Cavan Gonzales (1970-)

- Derek Gonzales (1986-)

- Kathy Wan Povi Sanchez (1950-) & Gilbert Sanchez

- Corrine Sanchez

- Gilbert Abel Sanchez

- Liana Sanchez

- Wayland Sanchez

- Evelyn Than-Povi Garcia

- Myra Garcia

- Berlinda Garcia

- Myra Garcia

- Peter Pino

- Barbara Tahn-Moo-Whe Gonzales (1947-) & Robert Gonzales

- Viola Martinez/Sunset Cruz & Johnnie Cruz Sr.

- Beverly Martinez (1960-1987)

- Marvin Martinez (1964-) and Frances Martinez

- Marvin Lee Martinez

- Johnnie Cruz Jr. (1975-)

- George Martinez (1943-) & Pauline Martinez (Santa Clara)(1950-)

- Popovi Da (1921-1971) & Anita Da

- Tony Da (1940-2008)

- Adam Martinez (1903-2000) and Santana Roybal Martinez (1909-2002)

- Maximiliana Montoya (1885-1955) & Cresencio Martinez (1879-1918)

- Juanita Vigil (1898-1933) & Romando Vigil (1902-1978)

- Carmelita Vigil (1925-1999) & Nicholas Cata

- Martha Appleleaf (1950-)

- Erik Fender (1970-)

- Gloria Maxey (d. 1999)

- Angelina Maxey (1970-)

- Jessie Maxey (1972-)

- Martha Appleleaf (1950-)

- Carmelita Vigil (Dunlap) (1925-1999) & Carlos Dunlap (d. 1971)

- Carlos Sunrise Dunlap (1958-1981)

- Cynthia Star Flower Dunlap (1959-)

- Jeannie Mountain Flower Dunlap (1953-)

- Linda Dunlap (1955-)

- Carmelita Vigil (1925-1999) & Nicholas Cata

- Philomena Peña & Juan Gonzales & Ramona Sanchez (Robert's mother)

- Robert Gonzales & Rose (Cata) Gonzales (San Juan)

- Tse-Pe & Dora Tse-Pe (Zia)

- Candace Tse-Pe

- Gerri Tse-Pe

- Irene Tse-Pe

- Tse-Pe (1940-2000) & Jennifer Tse-Pe (Sisneros) (second wife, San Juan/Santa Clara)

- Tse-Pe & Dora Tse-Pe (Zia)

- Oqwa Pi (Abel Sanchez)(1899-1971) & Tomasena (Cata) Sanchez (1903-1985, Rose Gonzales' sister)

- Skipped generation

- Russell Sanchez (1966-)

- Skipped generation

- Louis Wo-Peen Gonzales & Juanita Wo-Peen Gonzales (1909-1988)

- Adelphia Martinez

- Lorenzo Gonzales (adopted) (1922-1995)

- Blue Corn (Crucita Calabaza - Lorenzo's sister) (1921-1999)

- Robert Gonzales & Rose (Cata) Gonzales (San Juan)

- Nicolasa Peña Montoya (1863-1904) & Juan Cruz Montoya

- Tonita Peña (1847-c. 1910)

- Anastacia Peña (c. 1876-)

- Luisa Peña

- Isabel Peña (c. 1881-) & Pasqual Martinez

- Teracita Martinez

- Petronella Martinez & Emiliano Abeyta (San Juan/Ohkay Owingeh)

- Philopeta Martinez (1925-) & Patrick Torres

- Elvis Torres (1960-)

- Torivia Martinez

- Philopeta Martinez (1925-) & Patrick Torres

- Anastacia Peña (c. 1876-)

- Santana Peña (1846-) & Antonio Domingo Peña (1841-)

Some of the above info is drawn from Pueblo Indian Pottery, 750 Artist Biographies, by Gregory Schaaf, © 2000, Center for Indigenous Arts & Studies

Other info is derived from personal contacts with family members and through interminable searches of the Internet.

Copyright © 1998-2025 by