Click or tap to see a larger version

Richard Ebelacker, Santa Clara, A black jar with a recurved neck and carved with a two-panel stylized avanyu geometric design

Santa Clara

$ 3600

pksc4g251

A black jar with a recurved neck and carved with a two-panel stylized avanyu geometric design

6.75 in L by 6.75 in W by 6.75 in H

Condition: Excellent

Signature: Richard L. Ebelacker Santa Clara Pueblo

Tell me more! Buy this piece!

(505) 986-1234 - www.andreafisherpottery.com - All Rights Reserved

Richard Ebelacker

1946-2010

Santa Clara

Richard Ebelacker was born into Santa Clara Pueblo in March 1946. His parents were Virginia Ebelacker and Robert Ebelacker. His maternal grandparents were Margaret Tafoya and Alcario Tafoya. He grew up learning how to make pottery from his mother and grandmother. Margaret, especially, taught him how to make exceptionally large redware and blackware pots.

Richard is the great grandson of Sarafina Tafoya, who is the mother of Margaret Tafoya. Margaret's oldest child is Virginia Ebelacker and Virginia's oldest child is Richard. All four of them were the only potters at Santa Clara who had the skill to make gigantic storage jars, some as large as 36 inches high. 36 inches is the height of your normal kitchen counter.

Constructing a large storage jar, at one time used for grain, corn or other foodstuff, is outrageously difficult. First, you need an enormous amount of hand-dug, clean clay. Coiling the pot needs to be done in stages so the pot can dry enough to support each additional coil. The pot will collapse if it cannot support itself.

Drying is slow to avoid cracking. Once the pot is dry, sanding the surface smooth creates mountains of dust. Afterwards, polishing is a real challenge. First, a slip (watery clay) is painted on to the surface and then, with a smooth river stone, the potter must rub the surface of the entire pot with the stone in a single sitting. This polishing is repeated over and over until a lustrous sheen is created. If you stop polishing, you run the risk of leaving a mark where you begin again.

The large pots were rarely decorated, and, if so, there was only a bear paw print. The most treacherous part of the process is the firing. Building a fire that big is dangerous and if the heat is not even over the entire pot, you run the risk of one area of the piece shrinking faster than the rest and having the pot crack or fall apart. Then just moving that heavy monster piece can be difficult. To make those big pieces takes strength, time, patience, determination and even more strength and talent. Today, the only Santa Clara potters who make larger pieces (but not as big as storage jars) are James Ebelacker, Richard's brother, and Jason Ebelacker, Richard's son.

Richard exhibited his gigantic pots at Santa Fe's Indian Market for 25 years and won countless awards. At the Market, potters still display their pieces on folding tables. Richard's pots were so big and tall, that every time I walked by his booth, I could never tell whether he was there, tending his work. He would peek out between or around his "forest" of pottery. He created his own shade on those hot August days.

Around 1968, Richard, along with his brother James, were encouraged by their mother Virginia to make pottery. After graduating from high school, Richard served in the U.S. Marine Corps, returning from Vietnam in 1966 to a job as a fireman in Los Alamos, New Mexico. He also was employed part time at the Los Alamos Scientific Laboratory. With two jobs, he did not have much extra time to make many of those large, time consuming pieces. He most enjoyed forming the pots and really disliked sanding them. Apparently, he was allergic to the dust! Richard died in 2010.

Some of the Awards won by Richard

- 2004 Santa Fe Indian Market. Class II - Pottery, Div. C - Traditional pottery, carved or incised, in style of San Juan, San Ildefonso, Santa Clara, Cat. 1006 - Miscellaneous, First Place

- 2001 Santa Fe Indian Market. Class. II - Pottery, Div. B - Traditional, Cat. 906 - Miscellaneous, Third Place; Div. C - Traditional, carved or incised, Best of Division; - Cat. 1005 - Miscellaneous, First Place

- 1999 Santa Fe Indian Market. Class II - Pottery, Div. A - Traditional, Cat. 902 - Jars, First Place and Second Place; - Cat. 906 - Wedding Vases, Third Place

- 1997 Santa Fe Indian Market. Class II - Pottery, Div. A - Traditional, Cat. 902 - Jars, Third Place; - Cat. 906 - Wedding vases, Second Place; - Div. C - Traditional, Cat. 1006 - Wedding vases, First Place

- 1996 Santa Fe Indian Market. Class. II - Pottery, Div. A - Traditional, Cat. 902 - Jars, Third Place; - Cat. 906 - Wedding vases, Third Place; - Div. B - Traditional, Cat. 906 - Wedding vases, Third Place

- 1995 Santa Fe Indian Market. Class. II - Pottery, Cat. 905 - Other bowls, Third Place

- 1994 Santa Fe Indian Market. Class II - Pottery, Div. D - Traditional, carved, Cat. 1106 - Wedding Jars, Second Place

- 1993 Santa Fe Indian Market. Class II - Pottery, Large Pottery Award; - Div. B - Traditional undecorated, Best of Division; - Cat. 902 - Jars, Second and Third Place; - Cat. 906 - Wedding vases, First Place; - Cat. 1102 - Jars, Second Place

- 1992 Santa Fe Indian Market. Class II - Pottery, Cat. 902 - Jars, First Place and Second Place; - Div. B - Traditional, undecorated, Best of Division

- 1991 Santa Fe Indian Market. Class. II - Pottery, Best of Classification; - Div. B - Best of Division; - Cat. 902 - Jars, First Place

- 1988 Santa Fe Indian Market. Class. II - Pottery, jar over 8 inches tall, Second Place

- 1986 Santa Fe Indian Market. Class. II - Pottery, carved red jar, First Place - Carved red jar with serpent design, Second Place - Red water jar, Second Place - Carved red jar, Third Place

- 1985 Santa Fe Indian Market. Class. II - Pottery, Red water jar, First Place - Red wedding vase, Second Place

- 1983 Santa Fe Indian Market. Class. II - Pottery, Div. D - Traditional, carved, Third Place

- 1982 Santa Fe Indian Market. Class. II - Pottery, traditional carved pottery, Second Place

- 1981 Santa Fe Indian Market, Class. II - Pottery, Best of Division - Traditional carved pottery, First Place

- 1980 Santa Fe Indian Market. Traditional carved pottery, Third Place

- 1979 Santa Fe Indian Market. Second Place for a black and white jar

- 1978 Santa Fe Indian Market. First Place for a carved water jar

- 1977 Santa Fe Indian Market. Second Place for a melon bowl;

- Third Place for a wedding vase

Santa Clara Pueblo

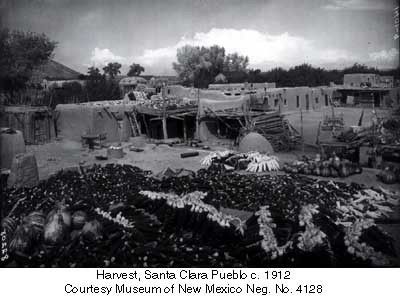

Ruins at Puye Cliffs, Santa Clara Pueblo

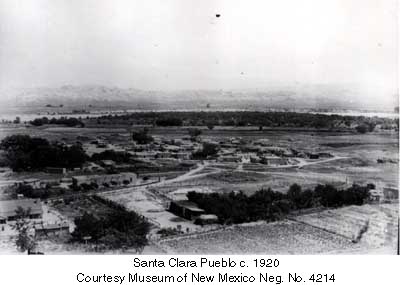

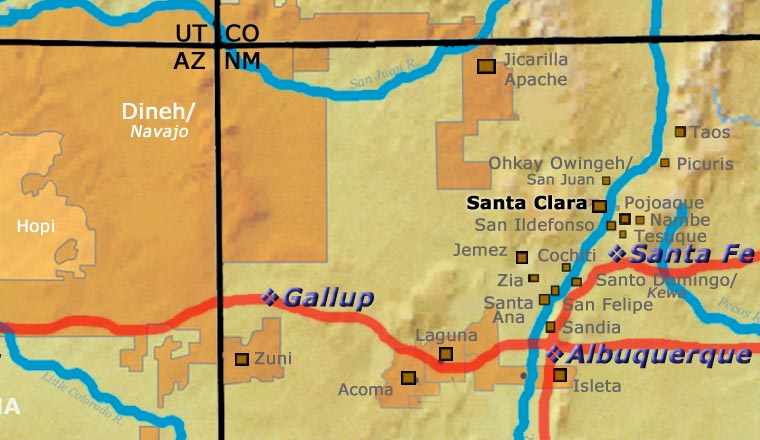

Santa Clara Pueblo straddles the Rio Grande about 25 miles north of Santa Fe. Of all the pueblos, Santa Clara has the largest number of potters.

The ancestral roots of the Santa Clara people have been traced to ancient pueblos in the Mesa Verde region in southwestern Colorado. When that area began to get dry between about 1100 and 1300 CE, some of the people migrated eastward, then south into the Chama River Valley where they constructed several pueblos over the years. One was Poshuouinge, built about 3 miles south of what is now Abiquiu on the edge of the Jemez foothills above the Chama River. Eventually reaching two and three stories high, and with up to 700 rooms on the ground floor, Poshuouinge was occupied from about 1375 CE to about 1475. Drought then again forced the people to move, some of them going to the area of Puye (on the eastern slopes of the Pajarito Plateau of the Jemez Mountains) and others downstream to Ohkay Owingeh (San Juan Pueblo, along the Rio Grande). Beginning around 1580 CE, drought forced the residents of the Puye area to relocate closer to the Rio Grande and they founded what we now know as Santa Clara Pueblo on the west bank of the river, with San Juan Pueblo to the north and San Ildefonso Pueblo to the south.

In 1598 the seat of Spanish government was established at Yunque, near San Juan Pueblo. The Spanish proceeded to antagonize the Puebloans so badly that that government was moved to Santa Fe in 1610, for their own safety.

Spanish colonists brought the first missionaries to Santa Clara in 1598. Among the many things they forced on the people, those missionaries forced the construction of the first mission church around 1622. However, like the other pueblos, the Santa Clarans chafed under the weight of Spanish rule. As a result, they were in the forefront of the Pueblo Revolt of 1680. One Santa Clara resident, a mixed black and Tewa man named Domingo Naranjo, was one of the rebellion's ringleaders. However, the pueblo unity that allowed them to chase the Spanish out fell apart shortly after their success, especially after Popé died.

When Don Diego de Vargas came back to the area in 1694, he found most of the Santa Clarans on top of nearby Black Mesa (with the people of San Ildefonso). A six-month siege didn't subdue them so finally, the two sides negotiated a treaty and the people returned to their pueblos. However, successive invasions and occupations by northern Europeans took their toll on all the tribes over the next 250 years. Then the swine flu pandemic in 1918 almost wiped them out.

Today, Santa Clara Pueblo is home to as many as 2,600 people and they comprise probably the largest per capita number of artists of any North American tribe (estimates of the number of potters run as high as 1-in-4 residents).

Today's pottery from Santa Clara is typically either black or red. It is usually highly polished and designs might be deeply carved or etched ("sgraffito") into the pot's surface. The water serpent, (avanyu), is a very common traditional design motif on Santa Clara pottery. Another motif comes from the legend that a bear helped the people find water during a drought. The bear paw has appeared on much of their pottery ever since.

Santa Clara has received a lot of distinction because of the evolving artistry the potters have brought to their craft. Not only did this pueblo produce excellent black and redware, several notable innovations helped move pottery from the realm of utilitarian vessels into the domain of art. Different styles of polychrome redware emerged in the 1920s-1930s. In the early 1960s experiments with stone inlay, incising and double firing began. Modern potters have also extended the tradition with unusual shapes, slips and designs, illustrating what one Santa Clara potter said: "At Santa Clara, being non-traditional is the tradition." (This refers strictly to artistic expression; the method of creating pottery remains traditional).

Santa Clara Pueblo is home to a number of famous pottery families: Tafoya, Baca, Gutierrez, Naranjo, Suazo, Chavarria, Garcia, Vigil, and Tapia - to name a few.

Santa Clara Pueblo at Wikipedia

Pueblos of the Rio Grande, Daniel Gibson, ISBN-13:978-1-887896-26-9, Rio Nuevo Publishers, 2001

Upper photo courtesy of Einar Kvaran, Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 3.0 Unported License

Margaret Tafoya Family Tree

Disclaimer: This "family tree" is a best effort on our part to determine who the potters are in this family and arrange them in a generational order. The general information available is questionable so we have tried to show each of these diagrams to living members of each family to get their input and approval, too. This diagram is subject to change should we get better info.

Note: Sarafina (Gutierrez) Tafoya was the sister of Pasqualita Tani Gutierrez.

- Sarafina Tafoya (1863-1949) & Geronimo Tafoya

- Margaret Tafoya (1904-2001) & Alcario Tafoya (d. 1995)

- Mary Ester Archuleta (1942-2010)

- Barry Archuleta

- Bryon Archuleta

- Sheila Archuleta

- Jennie Trammel (1929-2010)

- Karen Trammel Beloris

- Virginia Ebelacker (1925-2001)

- James Ebelacker (1960-) & Cynthia Ebelacker

- Jamelyn Ebelacker

- Sarena Ebelacker

- Richard Ebelacker (1946-2010) & Yvonne Ortiz

- Jason Ebelacker

- Jerome Ebelacker & Dyan Esquibel

- Andrew Ebelacker

- Nickolas Ebelacker

- James Ebelacker (1960-) & Cynthia Ebelacker

- Lee Tafoya (1926-1996) & Betty Tafoya (Anglo)

- Linda Tafoya (Oyenque)(Sanchez) (1962-)

- Phyllis Bustos Tafoya

- Mela Youngblood (1931-1990) & Walt Youngblood

- Nancy Youngblood (1955-)

- Christopher Cutler

- Joseph Lugo

- Sergio Lugo

- Nathan Youngblood (1954-)

- Nancy Youngblood (1955-)

- Toni Roller (1935-)

- Brandon Roller

- Cliff Roller (1961-)

- Deborah Morning Star Roller

- Jeff Roller (1963-)

- Jordan Roller

- Ryan Roller

- Susan Roller Whittington (1955-)

- Charles Lewis

- Tim Roller (1959-) & Clarissa Tafoya

- William Roller

- LuAnn Tafoya (1938-) & Sostence Tapia

- Michele Tapia Browning (1960-2025)

- Daryl Duane Whitegeese (1964-) & Rosemary Hardy

- Shirley Cactus Blossom Tafoya (1947-2010)

- Meldon Tafoya

- Mary Ester Archuleta (1942-2010)

- Christina Naranjo (1891-1980) & Jose Victor Naranjo (1895-1942)

- Mary Cain (1916-2010)

- Billy Cain (1950-2005)

- Joy Cain (1947-)

- Linda Cain (1949-)

- Autumn Borts-Medlock (1967-)

- Tammy Garcia (1969-)

- Douglas Tafoya

- Marjorie Tafoya Tanin

- Teresita Naranjo (1919-1999)

- Stella Chavarria (1939-)

- Denise Chavarria (1959-)

- Joey Chavarria (1964-1987)

- Sunday Chavarria (1963-)

- Stella Chavarria (1939-)

- Cecilia Naranjo

- Sharon Naranjo Garcia (1951-)

- Judy Tafoya (1962-) & Lincoln Tafoya (1954-)

- Mida Tafoya (1931-2024)

- Sherry Tafoya (1956-)

- Phyllis Tafoya (1955-)

- Robert Tafoya

- Ethel Vigil

- Kimberly Garcia

- Mary Cain (1916-2010)

- Camilio Tafoya (1902-1995) & Agapita Silva (1904-1959)

- Joe Tafoya & Lucy Year Flower (1935-2012)

- Kelli Little Kachina (1967-2014)

- Myra Little Snow (1962-)

- Forrest Red Cloud Tafoya

- Shawn Tafoya (1968-)

- Joseph Lonewolf (1932-2014) & Katheryn Lonewolf

- Greg Lonewolf (1952-)

- Rosemary Apple Blossom Lonewolf (1954-) & Paul Speckled Rock (1952-2017)

- Adam Speckled Rock

- Susan Romero

- Grace Medicine Flower (1938-)

- Joe Tafoya & Lucy Year Flower (1935-2012)

- Dolorita Padilla (1897-1960) & Alberto Padilla (1898-)

- Tomacita Tafoya Naranjo (1884-1918) & Agapita Naranjo

- Nicolasa Naranjo (c.1910-) & Jose G. Tafoya

- Howard Naranjo & Linda Naranjo

- Nicolasa Naranjo (c.1910-) & Jose G. Tafoya

Some of the above info is drawn from Pueblo Indian Pottery, 750 Artist Biographies, by Gregory Schaaf, © 2000, Center for Indigenous Arts & Studies

Other info is derived from personal contacts with family members and through interminable searches of the Internet.

Copyright © 1998-2025 by