Click or tap to see a larger version

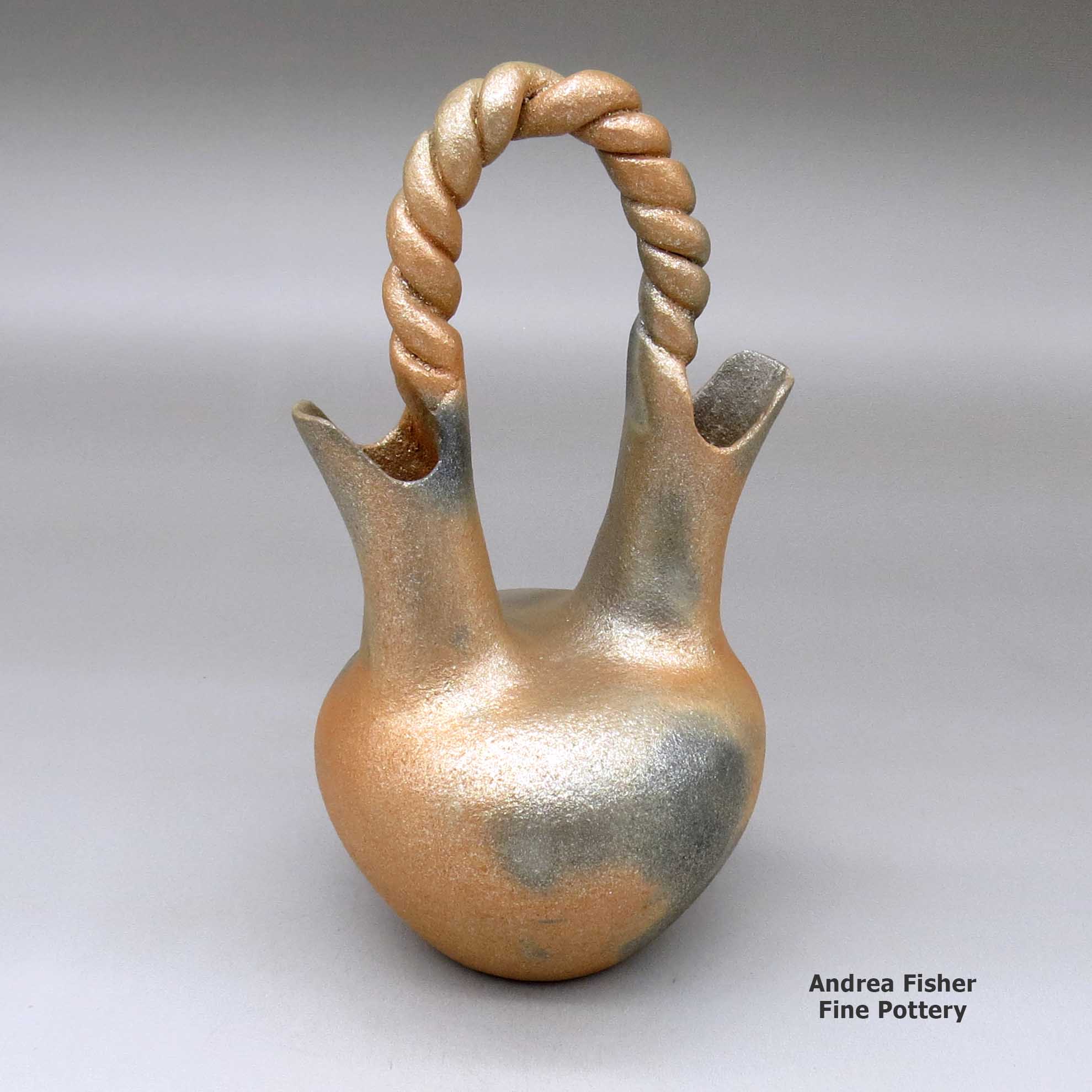

Angie Yazzie, Taos, A golden micaceous wedding vase with a twisted handle and fire clouds

Taos

$ 725

shta4f343

A golden micaceous wedding vase with a twisted handle and fire clouds

5.25 in L by 6 in W by 10.75 in H

Condition: Very good, with a small chip on the lip of a spout, see image 2, priced accordingly

Signature: Angie Yazzie Taos Pueblo

Date Created: 1991

Tell me more! Buy this piece!

(505) 986-1234 - www.andreafisherpottery.com - All Rights Reserved

Angie Yazzie

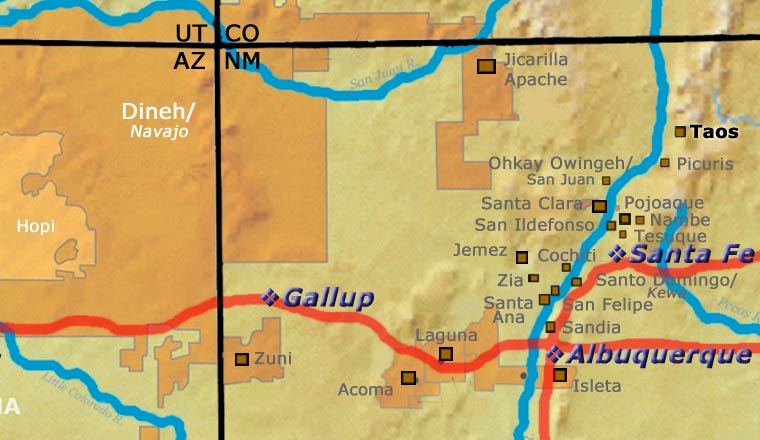

Taos

Angie Yazzie was born into Taos Pueblo in 1965. Her parents were Mary A. Archuleta of Taos Pueblo and Nick Yazzie of the Dineh (Navajo). In keeping with Pueblo tradition Angie was raised at Taos Pueblo.

Angie tells us she began making pottery when she was nine years old after being introduced to the basics by her mother and her maternal grandmother, Isabel Archuleta. Angie said she lived with her maternal grandparents for several years as a child and through them and their shop at the pueblo, she was exposed to the whole range of Pueblo arts and crafts. Clay Mother, though, is who Angie has heard calling her to work all these years.

After learning the barest basics, Angie struck out on her own and learned to make large golden and black micaceous ollas, like the ollas Taos was famous for making a hundred and more years ago. Micaceous clay has tiny flecks of mica spread throughout the clay. That mica makes it possible for a pueblo pot to hold liquids for cooking or storing. There are two seams of micaceous clay on the lands of Taos Pueblo: one golden and one black.

Angie has told us her favorite shape to make is a large, fluted water jar, slipped with micaceous clay. It is exactly that type of jar that has earned her Best of Division and First Place ribbons at the Heard Museum Guild Indian Art Fair, Best of Division and First, Second and Third Place ribbons at the SWAIA Santa Fe Indian Market and First Place ribbons at the Eight Northern Pueblos Arts and Crafts Show. Angie recently had a piece placed on display at the Winona State College Museum in Winona, Minnesota.

Angie says she still gets her inspiration from her fond memories of her maternal grandmother. At the same time, she loves to look at other artists creations and talk to them about how they made it.

Some of the Awards Angie has Won

- 2020 Heard Museum Guild Indian Fair & Market: Judge's Award - Upton Ethelbah Greyshoes, Jr. Awarded for artwork: "Give Me Water"

- 2018 Santa Fe Indian Market: Classification II - Pottery, Division A - Traditional Unpainted Pottery, Category 502 - Micaceous Ware in the style of Taos, Nambe, Picuris, any form: First Place

- 2018 Heard Museum Guild Indian Fair & Market, Classification II - Pottery, Division B - Unpainted, including ribbed, native clay, hand built, fired out-of-doors: First Place. Awarded for artwork: Black Fluted Vase

- 2018 Heard Museum Guild Indian Fair & Market, Classification II - Pottery, Division G - Pottery miniatures not to exceed three (3) inches at its greatest dimension: Honorable Mention. Awarded for artwork: Rectangle Prayer Plate

- 2017 Santa Fe Indian Market: Classification II - Pottery: Best of Classification

- 2017 Santa Fe Indian Market: Classification II - Pottery, Division A - Traditional Unpainted Pottery: Best of Division

- 2017 Santa Fe Indian Market: Classification II - Pottery, Division A - Traditional Unpainted Pottery, Category 502 - Micaceous Ware in the style of Taos, Nambe, Picuris, any form: First Place

Taos Pueblo

North House, Taos Pueblo

Today's Taos Pueblo consists of two main structures, both of which are counted among the oldest continuously inhabited structures in the United States. The location straddles the Rio Pueblo de Taos (also known as Red Willow Creek), whose headwaters rise in the nearby Sangre de Cristo Mountains. The pueblo was designated a National Historic Landmark in 1960 and was designated a UNESCO World Heritage Site in 1992.

The native language of Taos Pueblo is Northern Tiwa, a member of the Tanoan family of languages. It has been suggested that Northern Tiwa developed when late-arriving Tewa migrants passed across the already-overcrowded Tewa Basin around 1300 CE, and entered into the Pot Creek area to merge with the Tanoans already there.

The "precursor" pueblo to Taos was a pueblo now known as Pot Creek Pueblo. At its height, Pot Creek Pueblo might have been the largest pueblo in the Southwest. However, some kind of trouble developed at Pot Creek in the early 1300s CE, and part of the pueblo was burned with the residents scattering in different directions. Many went a few miles north to a neighboring Tanoan pueblo (Taos) and merged with them. Others went southeast, into a high pass in the mountains where they founded Picuris Pueblo.

Taos Pueblo was a center of trade long before the Spanish arrived. The pueblo served as a contact point between the Rio Grande Pueblos to the south and the Comanche, Apache and Ute to the east, north and northeast. Every fall when the annual trade fair was happening, Taos Pueblo became a neutral zone where fighting and raiding were banned for the duration of the fair. The arrival of the Spanish in 1540 didn't interfere with the trade fair cycle but after they returned in 1598, they did try to impose taxes on everyone.

Around 1620 Jesuit priests oversaw the construction of the first mission of San Geronimo de Taos. Friction between the tribe and the Spanish led to the killing of a resident priest and destruction of the church in 1660. The church was rebuilt, only to be destroyed again and two resident priests killed in the opening moments of the Pueblo Revolt of 1680. The Spanish were evicted from northern Nuevo Mexico that year but returned in force in 1692. By 1700, the third mission church at Taos was under construction.

For a few years, the tribe and the Spanish got along, forced to be amicable in order to deal with their common enemies: Ute, Apache and Comanche raiders. That pressure was relieved in 1776 when Governor Juan Bautista de Anza and his troops killed virtually the entire upper hierarchy of the Comanche tribe in the Battle of Cuerno Verde, near Greenhorn Mountain in southern Colorado.

American fur trappers and traders first appeared in the area in the early 1800s. Things changed in 1820 when Mexico declared independence and trade wagons began rolling over the Santa Fe Trail. The American military arrived in 1847, in the beginning of the Mexican-American War. That military presence quickly led to the Taos Rebellion of 1847, a rebellion which saw Governor Charles Bent and several other prominent Americans killed. A few days later American troops and armed citizens arrived from Santa Fe and, thinking the rebels had taken refuge in the mission church, they destroyed the church and killed many innocent women and children who were hiding inside it. That effectively ended the rebellion. After a short trial, 17 of the surviving rebels were hanged from trees surrounding the plaza in the nearby non-Indian village of Taos. A new mission church was constructed around 1850 near the west gate of the pueblo wall but the ruins of the old church are still visible today.

One result of the Taos Rebellion is that the tribe has never signed a peace treaty with the United States Government. That led to President Theodore Roosevelt using an Executive Proclamation to remove some 48,000 acres of the pueblo's mountain land and combine that with the fledgling Carson National Forest in 1906. That land was a point of major contention between the pueblo and Congress until it was returned to the tribe by President Richard M. Nixon in 1970. An additional 764 acres was returned to the tribe in 1996.

Today the community of Taos Pueblo is considered one of the most private, secretive and conservative of all the pueblos, even though the Pueblo of Taos offers more on-site shops for visitors than any other pueblo.

Taos potters have been making pottery for hundreds of years, much of it slipped with micaceous clay so that it could be used for cooking purposes. For many years Taos pottery was traded to the Apache, Ute, Arapaho and Comanche who came to the annual Taos trade fair, in return for buffalo meat and buffalo hides. Traditional Taos micaceous pottery is known for its glittery tan or yellow gold appearance. Generally, there was no painted decoration but there might be some form of sculpted detail. Today's Taos potters produce a variety of traditional micaceous pots.

Taos Pueblo at Wikipedia

Pueblo of Taos official website

Pueblos of the Rio Grande, Daniel Gibson, ISBN-13:978-1-887896-26-9, Rio Nuevo Publishers, 2001

Photo courtesy of Elisa Rolle, Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 3.0 Unported License

The Story of

the Wedding Vase

as told by Teresita Naranjo of Santa Clara Pueblo

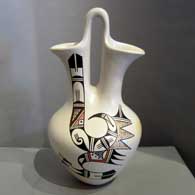

Helen Naha

Hopi

Wilma Baca Tosa

Jemez Pueblo

Margaret Tafoya

Santa Clara Pueblo

The Wedding Vase has been used for a long, long time in Indian Wedding Ceremonies.

After a period of courtship, when a boy and girl decide to get married, they cannot do so until certain customs have been observed. The boy must first call all his relatives together to tell them that he desires to be married to a certain girl. If the relatives agree, two or three of the oldest men are chosen to call on the parents of the girl. They pray according to Indian custom and the oldest man will tell the parents of the girl what their purpose is in visiting. The girl's parents never give a definite answer at this time, but just say that they will let the boy's family know their decision later.

About a week later, the girl calls a meeting of her relatives. The family then decides what answer should be given. If the answer is “no” that is the end of it. If the answer is “yes” then the oldest men in her family are delegated to go to the boy's home, and to give the answer, and to tell the boy on what day he can come to receive his bride-to-be. The boy must also notify all of his relatives on what day the girl will receive him, so that they will be able to have gifts for the girl.

Now the boy must find a Godmother and Godfather. The Godmother immediately starts making the wedding vase so that it will be finished by the time the girl is to be received. The Godmother also takes some of the stones which have been designated as holy and dips them into water, to make it holy water. It is with this holy water that the vase is filled on the day of the reception.

The reception day finally comes and the Godmother and Godfather lead the procession of the boy's relatives to the home of the girl. The groom is the last in line and must stand at the door of the bride's home until the gifts his relatives have brought have been opened and received by the bride.

The bride and groom now kneel in the middle of the room with the groom's relatives and the bride's parents praying all around them. The bride then gives her squash blossom necklace to the groom's oldest male relative, while the groom gives his necklace to the bride's oldest male relative. After each man has prayed, the groom's necklace is placed on the bride, and the bride's is likewise placed on the groom.

After the exchange of squash blossom necklaces and prayers, the Godmother places the wedding vase in front of the bride and groom. The bride drinks out of one side of the wedding vase and the groom drinks from the other. Then, the vase is passed to all in the room, with the women all drinking from the bride's side, and the men from the groom's.

After the ritual drinking of the holy water and the prayers, the bride's family feeds all the groom's relatives and a date is set for the church wedding. The wedding vase is now put aside until after the church wedding.

Once the church wedding ceremony has occurred, the wedding vase is filled with any drink the family may wish. Once again, all the family drinks in the traditional manner, with women drinking from one side, and men the other. Having served its ceremonial purpose, the wedding vase is given to the young newlyweds as a good luck piece.

Copyright © 1998-2025 by