Click or tap to see a larger version

Clifford Kim Fragua, Jemez, A boy and girl riding on the back of a horse

Jemez

$ 250

zzje4d260m1

A boy and girl riding on the back of a horse

6.75 in L by 2.5 in W by 5 in H

Condition: Excellent

Signature: Clifford Kim Fragua

Date Created: 2024

Tell me more! Buy this piece!

(505) 986-1234 - www.andreafisherpottery.com - All Rights Reserved

Clifford Kim Fragua

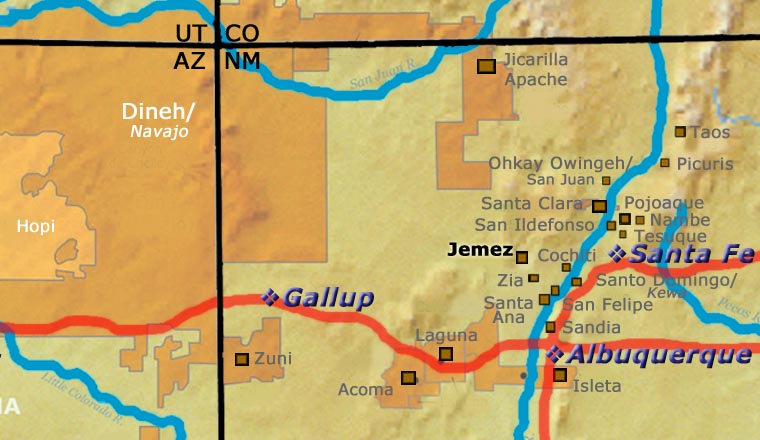

Jemez

Clifford Kim Fragua was born into Jemez Pueblo in 1957, the son of Felix and Grace L. Fragua. Among his siblings were Emily Fragua Tsosie, Carol Gachupin and Bonnie Fragua. Like them he learned to make pottery by watching and working with their mother as he grew up.

Clifford likes to make storytellers, Koshare clown figures, Corn Maidens, Nativities, children on horse figures and red-on-white and black-on-white jars, vases, bowls and ornaments. The largest storyteller he ever made stood 24 inches tall with 217 children. It earned him a First Prize ribbon at the Gallup InterTribal Ceremonial in 1992.

Jemez Pueblo

Ruins of San Jose de las Jemez Mission

As the drought in the Four Corners region deepened in the late 1200s, several clans of Towa-speaking people migrated southeastward from the Four Corners area to the Canyon de San Diego area the southern Jemez mountains, in what is now north-central New Mexico. Other clans of Towa-speaking people migrated southwest and settled in the Jeddito Wash area, below Antelope Mesa and southeast of Hopi First Mesa, in what is now northeastern Arizona. The migrations began in earnest in the mid 1200s and were mostly complete by the mid 1300s.

Archaeologist Jesse Walter Fewkes argues that potsherds found in the vicinity of the ruin at Sikyátki (near the foot of Hopi First Mesa) speak to the strong influence of earlier Towa-speaking potters on what became "Sikyátki Polychrome" pottery (Sikyátki was a village at the foot of First Mesa, destroyed before the first Hopi contact with the Spanish in 1540). Fewkes maintained that Sikyátki Polychrome pottery was the finest ceramic ware ever made in prehistoric North America.

Francisco de Coronado and his men arrived in the Jemez Mountains of Nuevo Mexico in 1539. By then the Jemez people had built several large masonry villages among the canyons and on some high ridges in the area. Their population was estimated at about 30,000 and they were among the largest and most powerful tribes in northern New Mexico. Some of their pueblos reached five stories high and contained as many as 3,000 rooms.

Because of the nature of the landscape they inhabited, growing food was very hard. So the Jemez became traders, too, and their people traded goods all over the Southwest and northern Mexico.

The arrival of the Spanish was disastrous for the Jemez and they resisted the Spanish with all their might. That led to many atrocities against the tribe until they rose up in the Pueblo Revolt of 1680 and evicted the Spanish from northern New Mexico. With the Spanish gone, the Jemez destroyed much of what they had built on Jemez land. Then they concentrated on preparing themselves for the eventual return of the hated priests and the Spanish military.

The Spanish returned in 1692 and their efforts to retake northern New Mexico bogged down as the Jemez fought them doggedly for four years. In 1696 many Jemez came together, killed a Franciscan missionary and then fled to join their distant relatives in the Jeddito Wash area. They remained at Jeddito Wash for several years before returning to the Jemez Mountains. As a result of that long ago contact, there are still strong ties between the Jemez and their cousins on Navajo territory at Jeddito. On their return to the Jemez Mountains, the people built the pueblo they now live in (Walatowa: The Place) and made peace with the Spanish authorities.

Some of the Jemez people had been making a type of plainware pottery (simple, undecorated, utilitarian) when they were still in the Four Corners area, while others had developed a distinctive type of black-on-white pottery. In moving to the Jemez Mountains, they brought their knowledge and techniques with them but had to adapt to the different materials available to work with. Over time, the Jemez got better in their agricultural practices and began trading agricultural goods to the people of Zia Pueblo in return for pottery. By the mid-1700s, the Jemez people were producing almost no pottery.

East of what is now Santa Fe is where the ruins of Cicuyé (Pecos) Pueblo are found. Cicuyé was a large pueblo housing up to 2,000 people at its height. The people of Cicuyé, and some in the northern Galisteo Basin, were the only other speakers of the Towa language in New Mexico. When that area fell on increasingly hard times (Apache and Comanche raids, European diseases, drought), Cicuyé was finally abandoned in 1838 when the last 17 residents moved to Jemez. The Governor of Jemez welcomed them and allowed them to retain many of their Cicuyé tribal offices (governorship and all). Descendants of former Cicuyé families still return to the site of their ancestral home every year to perform religious ceremonies in honor of their ancestors.

When general American interest in Puebloan pottery started to take off in the 1960s, the people of Jemez sought to recover that lost heritage. Today, the practice of traditional pottery-making is very much alive and well among the Jemez.

The focus of Jemez pottery today has mostly turned to the making of storytellers, nativities and other figures. Figures are an art form that now accounts for more than three-quarters of their pottery production.

Storytellers are usually grandparent figures with the figures of children attached to their bodies. The grandparents are pictured singing tribal songs and oral histories to their descendants. While this visual representation was first created at Cochiti Pueblo (a site in close geographical proximity to Jemez Pueblo) in the early 1960s by Helen Cordero, it speaks to the relationship between grandparents and grandchildren of every culture. Nativities, corn maidens, singing angels and many different animal forms are also popular among the potters of Jemez.

The pottery vessels made at Jemez Pueblo today are generally not black-on-white. Instead, the potters have adopted many colors, styles and techniques from other pueblos to the point where Jemez potters no longer have one distinct style of their own beyond that which stems naturally from the materials they themselves acquire from their surroundings: it doesn't matter what the shape or design is, the clay itself says uniquely "Jemez."

Jemez Pueblo at Wikipedia

Jemez Pueblo official website

Jemez Pueblo at the Catholic Encyclopedia

Pueblos of the Rio Grande, Daniel Gibson, ISBN-13:978-1-887896-26-0, Rio Nuevo Publishers, 2001

Prehistoric Hopi Pottery Designs, Jesse Walter Fewkes, ISBN-0-486-22959-9, Dover Publications, Inc., 1973

Emilia Loretto Family Tree

Disclaimer: This "family tree" is a best effort on our part to determine who the potters are in this family and arrange them in a generational order. The general information available is questionable so we have tried to show each of these diagrams to living members of each family to get their input and approval, too. This diagram is subject to change should we get better info.

- Emilia Loretto (c. 1910s-) & Carmalito Loretto

- Grace L. Fragua (c. 1920s-) & Felix Fragua

- Bonnie Fragua (1966-)

- Jonathan Fragua (c. 1985-)

- Caroline Fragua Gachupin & Joseph R. Gachupin Sr.

- Joseph E. Gachupin Jr.

- Cindy Fragua (1963-)

- Clifford Kim Fragua (1957-)

- Felicia Fragua (1964-) & Mike J. Curley

- Ardina Fragua (1980-)

- Loren Wallowing Bull (1988-)

- Linda Lucero Fragua and Phillip M. Fragua

- Chrislyn Fragua (1973-)

- Anissa Fragua (1994-)

- Chrislyn Fragua (1973-)

- Rose Fragua (1946-)

- Janeth Fragua (1964-)

- Emily Fragua Tsosie (1951-2021) & Leonard Tsosie (1941-)

- Darrick Tsosie (1977-)

- Joseph L. Tsosie (c. 1970s-)

- Lorna Tsosie (c. 1970s-)

- Robert Tsosie (c. 1970s-)

- Bonnie Fragua (1966-)

- Angela Loretto

- Anthony Loretto (1969-)

Some of the above info is drawn from Southern Pueblo Pottery, 2000 Artist Biographies, by Gregory Schaaf, © 2002, Center for Indigenous Arts & Studies. Other info is derived from personal contacts with family members and through interminable searches of the Internet and cross-examination of the data found.

Copyright © 1998-2025 by