Click or tap to see a larger version

Hubert Candelario, San Felipe, Micaceous gold-on-black seed pot with a carved organic design

San Felipe

$ 2200

gmsf4a129

Micaceous gold-on-black seed pot with a carved organic design

5.75 in L by 5.75 in W by 4.75 in H

Condition: Very good, rubbing on bottom

Signature: Hubert Candelario San Felipe NM

Date Created: 2002

Tell me more! Buy this piece!

(505) 986-1234 - www.andreafisherpottery.com - All Rights Reserved

Hubert Candelario

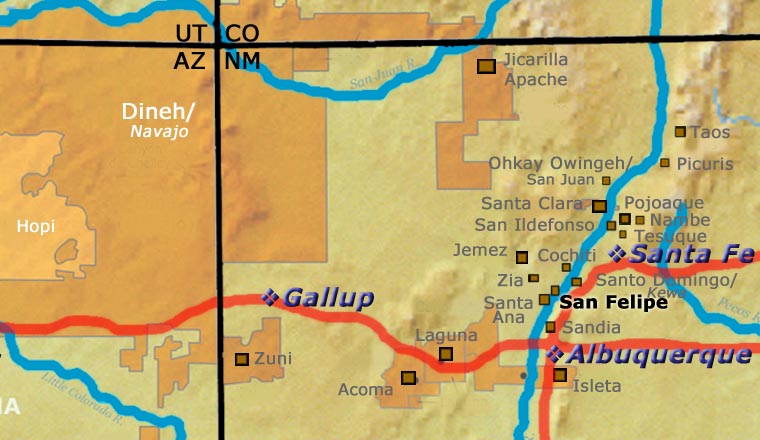

San Felipe

Historically, San Felipe hasn't been an active pottery center for more than 200 years. San Felipe residents obtained their pottery in trade with other pueblos, most often Zia Pueblo.

Hubert Candelario (Butterfly) was born into San Felipe Pueblo in 1965. He's been actively making pottery since 1987. But first, he earned an associate's degree in architectural design and drafting. That fostered his appreciation for structure and pure architectural form. He credits Maria Martinez as being a major influence in his pottery career. He also says Santa Clara potter Nancy Youngblood has had a direct impact on his work with her swirl carved melon pots.

Made the traditional way, his early works were polished redware. Today he is famous for his precisely carved puzzle pots, melon jars and pots perforated with circular or hexagonal holes. The structure of his pottery is formed with a red clay local to San Felipe. He completes the concept with layers of orange micaceous slip, burnished after each layer, to create his fabulous color and texture. The micaceous clay he gets from Nambe and Picuris Pueblos. He fires his pottery in a kiln to achieve an even color, free of fire clouds.

Hubert has won numerous awards including more than one First Place ribbon at the Santa Fe Indian Market. His work was included in the 2002 exhibit and catalog Changing Hands: Art without Reservation at the American Craft Museum in New York City. One of his large swirl-cut melon jars was also selected for the permanent collection at the Denver Art Museum. He signs his work: "Hubert Candelario, San Felipe Pueblo", followed by the date the piece was made.

Some Awards Won by Hubert

- 2025 Heard Museum Guild Indian Arts Fair & Market, Classification II - Pottery, First Place, Awarded for Micaceous pot with holes

- 2023 Santa Fe Indian Market, Classification II-E, Category 905, Miscellaneous, First Place

- 2020 Heard Museum Guild Indian Arts Fair & Market, Classification II - Pottery: Innovation Award for Pottery. Awarded for artwork: Oval Pot with Hole with Lid with Holes

- 2019 Santa Fe Indian Market, Classification II-E, Category 905 - Contemporary pottery, any form or design, using commercial clays/glazes, all firing techniques - Miscellaneous: First Place and Second Place

- 2019 Heard Museum Guild Indian Arts Fair & Market, Classification II-G - Pottery miniatures not to exceed three (3) inches at its greatest dimension: Second Place. Awarded for artwork: "Mini or Small Pot Flowing"

- 2019 Heard Museum Guild Indian Arts Fair & Market: Judge's Award - Jeremy Frey. Awarded for artwork: "Mica 9 Dragonfly Pot with Holes"

- 2018 Santa Fe Indian Market, Classification II - Pottery, Division F - Miniature pots, individual pieces under 3 inches in any dimension: Best of Division

- 2018 Santa Fe Indian Market, Classification II-F - Miniature pots, individual pieces under 3 inches in any dimension, Category 1002 - Contemporary: First Place

- 2018 Heard Museum Guild Indian Arts Fair & Market, Classification II - Pottery, Division G - Pottery miniatures not to exceed three (3) inches at its greatest dimension: Fist Place. Awarded for artwork: "Starmelon Mica Mini"

- 2017 Santa Fe Indian Market, Classification II - Pottery, Division E - Contemporary Pottery, any form or design, using commercial clays/glazes, all firing techniques, Category 905 - Miscellaneous: Honorable Mention

- 2017 Heard Museum Guild Indian Arts Fair & Market. Classification II Pottery, Division E - Any Design or Form with Native Materials, Kiln Fired Pottery: Second Place. Awarded for Artwork: Mica Spirit Bowl

- 2004 Santa Fe Indian Market. Classification II - Pottery, Division G - Non-traditional pottery, using traditional materials and techniques, any form or design, Category 1403 - Ribbed jars, wedding jars, vases and bowls, First Place

- 2004 Santa Fe Indian Market. Classification II - Pottery, Division G - Non-traditional pottery, using traditional materials and techniques, any form or design, Category 1411 - Miscellaneous: First Place

- 2004 Santa Fe Indian Market. Classification II - Pottery, Division K - Pottery miniatures, 3" or less in height or diameter, Category 1704 - Non-traditional forms or designs: First Place

- 2000 Santa Fe Indian Market. Classification II - Pottery, Division H - Non-traditional pottery, Category 1505 -Jars and vessels: Third Place

- 1997 Santa Fe Indian Market. Classification II - Pottery, Division H - non-traditional, Category 1505 - Jars: First Place

- 1997 Santa Fe Indian Market. Classification II - Pottery, Division H - Non-traditional, Category 1507 - Bowls: Third Place

- 1995 Santa Fe Indian Market. Classification II - Pottery, Division H - Non-traditional, Category 1603 - Jars and vases: First Place

- 1995 Santa Fe Indian Market. Classification II - Pottery, Division H - Non-traditional, Category 1604 - Bowls: Third Place

Some Exhibits that featured pieces by Hubert

- Breaking the Mold. Denver Art Museum. October 7, 2006 - August 19, 2007

- Breaking the Surface: Carved Pottery Techniques and Designs. Heard Museum. Phoenix, Arizona. October 2004 - October 2005

- Indian Market: New Directions in Southwestern Native American Pottery. Peabody Essex Museum. Salem, Massachusetts. November 16, 2001 - March 17, 2002

- Exhibition of New Works. Gallery 10. Scottsdale, Arizona. March 28, 1996

San Felipe Pueblo

San Felipe Pueblo today

During the great migrations of the 13th century from the Four Corners area to the valley of the Rio Grande, the people of Cochiti, Santo Domingo and San Felipe were one tribe, carrying with them the heart of what we now know as the Eastern Keres culture and religion. Archaeologists feel they mostly traveled from the Four Corners area around the north side of the Gallinas Highlands and the Jemez Mountains, staying south of the simultaneous Tewa migration happening in the Chama and Ojo Caliente River valleys. On arriving near the Rio Grande they settled in Frijole Canyon, on the southeastern side of the Pajarito Plateau. In the area now known as Bandelier National Monument, they built the village of Tyuonyi, and dug many residences into the soft volcanic tufa walls of the canyon. However, over time the Pajarito Plateau got too dry, too, and the people decided to move downstream into the valley of the larger Rio Grande. Once at the Rio Grande, they decided to keep moving south as the east bank was occupied by the Tewa and Tanoan people. Disagreements among the Keres over where to settle split the people into what is now the Cochiti, Santo Domingo and San Felipe tribes.

When Francisco de Coronado arrived in 1540, there were several Tiwa pueblos in the Middle Rio Grande area. He and his men attacked them all, stealing whatever food they could and inadvertently making sure all the natives were exposed to European diseases. When the Spanish came back in 1598, the Tiwa had been reduced from fifteen villages to two: Isleta and Alameda (now Sandia), and both were off to the south. Instead, there were now two Keres-speaking villages, one on either side of the Rio Grande, in the valley directly north of the ruined pueblo at Kuaua (today's Bernalillo). The main Keresan villages were comprised of large two-and-three-story structures plus a couple hundred outlying dwellings. The Spanish Franciscan monks forced the San Felipes to build their first mission church on top of their main kiva, next to the east village, around 1600.

Part of the San Felipe ancestral home

The people of San Felipe participated in the Pueblo Revolt of 1680 but killed no Spaniards nor any priests. Governor Otermin returned with troops in 1681 and found San Felipe abandoned as the people had hidden themselves atop nearby Horn Mesa. The Spaniards looted and burned the pueblo before returning to Mexico. When Don Diego de Vargas came back in 1692, the people chose to surrender and be baptised rather than flee or fight. To test the peace they first settled atop nearby Santa Ana Mesa. A few years later they descended into the Rio Grande Valley and built the beginnings of today's pueblo.

San Felipe has always had more arable land than most of the other pueblos and is still known for its agricultural products, although in modern times, most residents commute off-pueblo to work. The long-held isolationism of the San Felipe people has contributed to the loss of many traditional activities, including the making of pottery. Most San Felipe potters active today either learned the art on their own or learned from artisans at other pueblos. The revival of San Felipe pottery tradition is further complicated by the fact so few people remember where good clay might be found on the pueblo lands.

Pueblos of the Rio Grande, Daniel Gibson, ISBN-13:978-1-887896-26-9, Rio Nuevo Publishers, 2001

Seed Pots

Acoma, Hopi, Isleta, Jemez, Laguna, San Felipe, San Ildefonso, San Juan, Santa Clara

Acoma Pueblo

Hopi

Santa Clara Pueblo

It was a matter of survival to the ancient Native American people that seeds be stored properly until the next planting season. Small, hollow pots were made to ensure that the precious seeds would be kept safe from moisture, light and rodents. After seeds were put into the pot, the small hole in the pot was plugged. The following spring the plug was removed and the seeds were shaken from the pot directly onto the planting area.

Today, seed pots are no longer necessary due to readily available seeds from commercial suppliers. However, seed pots continue to be made as beautiful, decorative works of art. The sizes and shapes of seed pots have evolved and vary greatly, depending on the vision of Clay Mother as seen through the artist. The decorations vary, too, from simple white seed pots with raised relief to multi-colored painted, raised relief and sgraffito designs, sometimes with inlaid gemstones and silver lids.

Santa Clara Pueblo

Jemez Pueblo

Acoma Pueblo

Copyright © 1998-2025 by