Click or tap to see a larger version

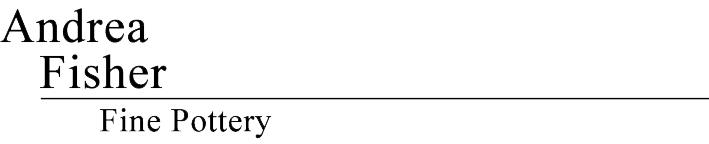

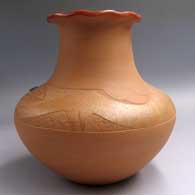

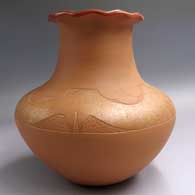

Russell Sanchez, San Ildefonso, Buff jar with a polished red pie crust rim, a band with a sgraffito avanyu and geometric design painted with a golden micaceous clay and with an inlaid turquoise

San Ildefonso

$ 8200

zzsi2b303

Buff jar with a polished red pie crust rim, a band with a sgraffito avanyu and geometric design painted with a golden micaceous clay and with an inlaid turquoise

9.75 in L by 9.75 in W by 9.75 in H

Condition: Excellent

Signature: Russell Sanchez San Ildefonso Pueblo

Date Created: 1989

Sale Price: $5300

Tell me more! Buy this piece!

(505) 986-1234 - www.andreafisherpottery.com - All Rights Reserved

Russell Sanchez

San Ildefonso

Russell Sanchez was born at San Ildefonso Pueblo in 1963. As a child he spent a lot of time with his grandparents, Oqwa Pi (an award-winning painter) and Pomasena Cata Sanchez, Rose Gonzales' younger sister. When Russell was about 8, Rose began teaching him the traditional way to make pottery. He says that one day when he was 11 or 12 he put a batch of small, newly finished black-on-black pots outside and Anita Da (Popovi Da's widow) came by and took a look. Then she told him, "I want you to start bringing me stuff" and that's how his pottery career really began to take off. After a while he also began working with Dora Tse-Pe, Rose's daughter-in-law, and from her he learned how to refine his process and attain a more perfect product. Since then he has developed his own techniques and has often been referred to as a modernist potter.

Because he grew up speaking Tewa, Russell was able to converse with his tribal elders and they told him where to go and what to look for when he went out in search of clay deposits. He found many of the old clay sources at San Ildefonso and has used them to help recreate many of the San Ildefonso styles from the 1800s, well before most San Ildefonso potters started creating black-on-black pots. He's done significant research into old styles and designs among the collections at the Museum of Indian Arts & Culture and the School for Advanced Research but when asked if he copies any he responds with a saying he learned in his youth: "This is mine, this is what I do. Take it and make it your own."

Russell is an avid outdoorsman and an expert with a kayak and a river raft. He's paddled rivers in Peru and Chile and challenged the Zambesi River in southern Africa. However, tamer rivers closer to home allow him to gather clay wherever he finds it. That has led to experiments with many different types of clay, even to the point of incorporating two or more different colors of clay into the same pot. He also often uses slips made of different colors of clay, including micaceous. His designs are painted, carved, incised and sometimes inlaid with turquoise and/or coral and heishi beads. For Russell, "traditional" doesn't mean being stuck in any one time period, it's more like growing and moving forward with everyone adding something else to the "traditional" as they travel their own paths.

Russell has won many awards over the years, including several First and Second Place ribbons at the Santa Fe Indian Market, the Eight Northern Pueblos Arts & Crafts Show and the Heard Museum Guild Indian Fair & Market. Collections of his work can be found at the Millicent Rogers Museum in Taos, New Mexico, the Museum of Natural History in Los Angeles, the Smithsonian Institute in Washington, DC, the Museum of Indian Arts & Culture in Santa Fe, New Mexico and the Heard Museum in Phoenix, Arizona. In 2017 Russell was awarded the 2017 New Mexico Governor's Award for Excellence in the Arts.

Some of the Awards Russell has Won

- 2024 Santa Fe Indian Market, Classification IID: Category 807 - Boundary, Second Place

- 2024 Santa Fe Indian Market, Classification IID: Category 806 - With added elements (like beads, feathers, stones, etc.) any form, Second Place

- 2024 Santa Fe Indian Market, Classification IID: Category 804 - Painted pottery, any form, First Place

- 2021 Heard Museum Guild Indian Fair & Market, Classification II - Pottery, Division C - Carved, native clay, hand built, fired out-of-doors: Honorable Mention. Awarded for artwork: "Black Sienna Jar"

- 2021 Heard Museum Guild Indian Fair & Market, Classification II - Pottery, Division D - Figurative, native clay, hand built: First Place. Awarded for artwork: "Red Bear Lidded Jar"

- 2021 Heard Museum Guild Indian Fair & Market, Classification II - Pottery, Division F - Any design or form with non-native materials, includes kiln-fired pottery: First Place. Awarded for artwork: "Black Gunmetal Water Jar"

- 2021 Heard Museum Guild Indian Fair & Market: Judge's Choice - Charles King. Awarded for artwork: "Red Bear Lidded Jar"

- 2020 Heard Museum Guild Indian Fair & Market, Classification II - Pottery: Best of Classification. Awarded for artwork: Pottery with Detached Lid

- 2020 Heard Museum Guild Indian Fair & Market, Classification II - Pottery, Division B - Unpainted, included ribbed, native clay, hand built, fired out-of-doors: First Place. Awarded for artwork: Pottery with Detached Lid

- 2020 Heard Museum Guild Indian Fair & Market, Classification II - Pottery, Division C - Carved, native clay, hand built, fired out-of-doors: First Place. Awarded for artwork: Pottery with Detached Lid

- 2020 Heard Museum Guild Indian Fair & Market, Classification II - Pottery, Division D - Figurative, native clay, hand built: First Place. Awarded for artwork: "Bear"

- 2019 Santa Fe Indian Market, Classification II - Pottery: Best of Classification

- 2019 Santa Fe Indian Market, Classification II - Pottery, Division D - Contemporary pottery, any form or design, using Native materials with or without added decorative elements, traditional firing techniques: Best of Division

- 2019 Santa Fe Indian Market, Classification II - Pottery, Division D - Contemporary pottery, any form or design, using Native materials with or without added decorative elements, traditional firing techniques, Category 801 - Sgraffito, any form: Second Place

- 2019 Santa Fe Indian Market, Classification II - Pottery, Division D - Contemporary pottery, any form or design, using Native materials with or without added decorative elements, traditional firing techniques, Category 804 - Painted, any form: First Place

- 2019 Santa Fe Indian Market, Classification II - Pottery, Division D - Contemporary pottery, any form or design, using Native materials with or without added decorative elements, traditional firing techniques, Category 805 - Figures, including sets: First Place

- 2018 Santa Fe Indian Market, Classification II - Pottery, Division D, Contemporary Pottery, Any Form or Design, Using Native Materials with or without Added Decorative Elements, Traditional Firing Techniques: Best of Division

- 2018 Santa Fe Indian Market, Classification II - Pottery, Division D, Contemporary Pottery, Any Form or Design, Using Native Materials with or without Added Decorative Elements, Traditional Firing Techniques, Category 801 - Sgraffito, Any Form: First Place

- 2018 Santa Fe Indian Market, Classification II - Pottery, Division D, Contemporary Pottery, Any Form or Design, Using Native Materials with or without Added Decorative Elements, Traditional Firing Techniques, Category 807 - Miscellaneous: First Place

- 2018 Santa Fe Indian Market: Tony Da Memorial Award, “New Vision in Pueblo Pottery.” For Excellence in the Creative and Innovative Use of Traditional Materials and Techniques

- 2018 Heard Museum Guild Indian Fair & Market: Judge's Award - Dr. Arthur Pelberg. Awarded for artwork: Black Mica Polished Water Jar

- 2017 Santa Fe Indian Market: Classification II - Pottery, Division D - Contemporary Pottery, any form or design, using Native materials with or without added decorative elements, traditional firing techniques, Category 801 - Sgraffito, any form: First Place

- 2017 Santa Fe Indian Market: Classification II - Pottery, Division D - Contemporary Pottery, any form or design, using Native materials with or without added decorative elements, traditional firing techniques, Category 805 - Figures, including sets: First Place

- 2017 New Mexico Governor's Award for Excellence in the Arts. Note: public ceremony held September 15, 2017, at the New Mexico Museum of Art, Santa Fe, New Mexico

- 2017 Heard Museum Guild Indian Fair & Market. Classification II Pottery, Division B - Unpainted, Including Ribbed Native Clay, Hand Built, Fired Out-of-Doors: First Place. Awarded for Art Work: Old Style Black Water Jar

- 2016 Heard Museum Guild Indian Fair & Market, Classification II - Pottery, Division D - Traditional - native clay, hand built, figurative: First Place

- 2016 Heard Museum Guild Indian Fair & Market, Classification II - Pottery, Division E - Non-traditional design or form with native materials: Second Place

- 2015 Heard Museum Guild Indian Fair & Market, Classification II - Pottery, Division D - Traditional - native clay, hand built, figurative: First Place

- 2014 Heard Museum Guild Indian Fair & Market, Classification II - Pottery, Division E - Non-traditional design or form with native materials: Second Place with Jennifer Tafoya

- 2014 Heard Museum Guild Indian Fair & Market, Classification II - Pottery, Division G - Pottery miniatures not to exceed three inches at its greatest dimension: Second Place with Nancy Youngblood

- 2013 Heard Museum Guild Indian Fair & Market, Classification II - Pottery: Best of Classification with Jennifer Moquino

- 2013 Heard Museum Guild Indian Fair & Market, Classification II - Pottery, Division D - Traditional, native clay, hand built, figurative: First Place with Jennifer Moquino

- 2013 Heard Museum Guild Indian Fair & Market, Classification II - Pottery, Division C - Traditional, native clay, hand built, carved: Second Place

- 2013 Heard Museum Guild Indian Fair & Market, Classification II - Pottery, Division F - Non-traditional design or form with non-native materials: Second Place with Jennifer Moquino

- 2012 Heard Museum Guild Indian Fair & Market, Classification II - Pottery, Division D - Traditional, native clay, figurative: Honorable Mention

- 2010 Heard Museum Guild Indian Fair & Market, Classification II - Pottery, Division D - Traditional, native clay, hand built, figurative: Honorable Mention

- 2010 Heard Museum Guild Indian Fair & Market, Classification II - Pottery, Division F - Non-traditional design or form with non-Native materials: First Place

- 2010 Heard Museum Guild Indian Fair & Market, Classification II - Pottery, Division F - Non-traditional design or form with non-Native materials: Second Place

- 2009 Heard Museum Guild Indian Fair & Market, Classification II - Pottery: Best of Classification

- 2009 Heard Museum Guild Indian Fair & Market, Classification II - Pottery, Division D - Traditional - hand-built, figurative: First Place

- 2009 Heard Museum Guild Indian Fair & Market, Classification II - Pottery, Division E - Non-Traditional Design or form with non-Native materials: Honorable Mention

- 2008 Heard Museum Guild Indian Fair & Market, Classification II - Pottery, Division C - Traditional, native clay, hand built, carved: First Place

- 2007 Heard Museum Guild Indian Fair & Market, Classification II - Pottery: Best of Classification

- 2007 Heard Museum Guild Indian Fair & Market, Classification II - Pottery, Division D - Traditional - hand-built, figurative: First Place

- 2007 Heard Museum Guild Indian Fair & Market, Classification II - Pottery, Division E - Non-Traditional Design or form with non-Native materials: First Place

- 2007 Heard Museum Guild Indian Fair & Market, Classification II - Pottery, Division F - Non-traditional design or form with non-native materials: First Place

- 2006 Heard Museum Guild Indian Fair & Market, Classification II - Pottery: Best of Classification

- 2006 Heard Museum Guild Indian Fair & Market, Classification II - Pottery, Division C - Traditional - Native clay/hand built/carved/ribbed/incised: Second Place

- 2006 Heard Museum Guild Indian Fair & Market, Classification II - Pottery, Division D - Traditional -native clay/hand built, figurative effigies, canteens, plates, storytellers, nativity scenes: Second Place

- 2006 Heard Museum Guild Indian Fair & Market, Classification II - Pottery, Division F - Non-traditional design or form with non-native materials: First Place

- 2004 Santa Fe Indian Market, Classification II - Pottery, Division H - Non-Traditional Pottery Using Traditional Materials and Techniques with Non-Traditional Decorative Elements, Category 1501 - Jars, Wedding Jars, and Vases: First Place

- 2004 Santa Fe Indian Market, Classification II - Pottery, Division H - Non-Traditional Pottery Using Traditional Materials and Techniques with Non-Traditional Decorative Elements, Category 1502 - Bowls: Second Place

- 2004 Santa Fe Indian Market, Classification II - Pottery, Division H - Non-Traditional Pottery Using Traditional Materials and Techniques with Non-Traditional Decorative Elements, Category 1503 - Combined Techniques, Any Shaped Vessel: Second Place

- 1979 Heard Museum Guild Indian Arts and Crafts Exhibit, Classification XI - Students - Grades 7 through 12, Division HH - Pottery: Third Place. Awarded for artwork: Pottery

- 1978 Heard Museum Guild Indian Arts and Crafts Exhibit, Classification X - Students - Grades 7 through 12, Division HH - Pottery: Second Place. Awarded for artwork: Seed pot

- 1978 Heard Museum Guild Indian Arts and Crafts Exhibit, Classification X - Students - Grades 7 through 12, Division HH - Pottery: Third Place. Awarded for artwork: Etched jar with turquoise

- 1977 Heard Museum Guild Indian Arts and Crafts Exhibit, Classification XI - Students - Grades 7 through 12, Division GG - Pottery: Second Place. Awarded for artwork: Wedding vase

- 1977 Heard Museum Guild Indian Arts and Crafts Exhibit, Classification XI - Students - Grades 7 through 12, Division GG - Pottery: Honorable Mention. Awarded for artwork: Black bear with stone

San Ildefonso Pueblo

Black Mesa at San Ildefonso Pueblo

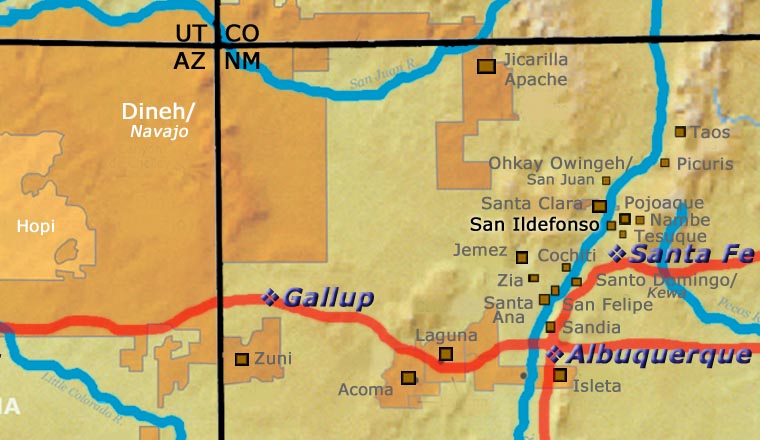

San Ildefonso Pueblo is located about twenty miles northwest of Santa Fe, New Mexico, west of Pojoaque, south of Santa Clara and straddling the Rio Grande. Although their ancestry has been traced to prehistoric pueblos in the Greater Mesa Verde area, the prehistoric pueblo at Tsankawi, in a non-contiguous parcel of Bandelier National Monument, is their most recent ancestral home. Tsankawi abuts the reservation on its northwest side.

Franciscan monks named the village after San Ildefonso and in 1617, forced the tribe to build a mission church on top of the village's main kiva. Before that the village was known as Powhoge, "where the water cuts through" (in Tewa). Today's pueblo was established as long ago as the 1300s. When the Spanish arrived in 1540, they estimated the village population at about 2,000.

That mission was destroyed during the Pueblo Revolt of 1680 and when Don Diego de Vargas returned to reclaim San Ildefonso in 1694, he found virtually all the Tewa people camped out on top of nearby Black Mesa. After an extended siege the two sides negotiated a treaty and the people returned to their villages. However, the next 250 years were not so good for them.

The swine flu pandemic of 1918 reduced the pueblo's population to about 90. Their population has grown to more than 600 since but the only economic activity available on the pueblo itself involves creating art in one form or another. The only other work is off-pueblo. San Ildefonso's population is small compared to neighboring Santa Clara Pueblo, but the pueblo maintains its own religious traditions and ceremonial feast days.

San Ildefonso is most known for being the home of the most famous Pueblo Indian potter, Maria Martinez. Many other excellent potters from this pueblo have produced quality pottery, too, among them: Blue Corn, Tonita and Juan Roybal, Dora Tse Pe and Rose Gonzales. Of course, the descendants of Maria Martinez are still important pillars of San Ildefonso's pottery tradition. Maria's influence reached far and wide, so far and wide that even Juan Quezada of the Mata Ortiz pottery renaissance in Chihuahua, Mexico, came to San Ildefonso to learn from her.

San Ildefonso Pueblo at Wikipedia

Pueblo of San Ildefonso official website

Pueblos of the Rio Grande, by Daniel Gibson

Photo is in the public domain

Micaceous Clay Pottery

Angie Yazzie

Taos

Christine McHorse

Navajo

Clarence Cruz

San Juan/Ohkay Owingeh

Micaceous clay pots are the only truly functional Pueblo pottery still being made. Some special micaceous pots can be used directly on the stove or in the oven for cooking. Some are also excellent for food storage. Some people say the best beans and chili they ever tasted were cooked in a micaceous bean pot. Whether you use them for cooking or storage or as additions to your collection of fine art, micaceous clay pots are a beautiful result of centuries of Pueblo pottery making.

Between Taos and Picuris Pueblos is US Hill. Somewhere on US Hill is a mica mine that has been in use for centuries. Excavations of ancient ruins and historic homesteads across the Southwest have found utensils and cooking pots that were made of this clay hundreds of years ago.

Not long ago, though, the making of micaceous pottery was a dying art. There were a couple potters at Taos and at Picuris still making utilitarian pieces but that was it. Then Lonnie Vigil felt the call, returned to Nambe Pueblo from Washington DC and learned to make the pottery he became famous for. His success brought others into the micaceous art marketplace.

Micaceous pots have a beautiful shimmer that comes from the high mica content in the clay. Mica is a composite mineral of aluminum and/or magnesium and various silicates. The Pueblos were using large sheets of translucent mica to make windows prior to the Spaniards arriving. It was the Spanish who brought a technique for making glass. There are eight mica mining areas in northern New Mexico with 54 mines spread among them. Most micaceous clay used in the making of modern Pueblo pottery comes from several different mines near Taos Pueblo.

As we understand it, potters Robert Vigil and Clarence Cruz have said there are two basic kinds of micaceous clay that most potters use. The first kind is extremely micaceous with mica in thick sheets. While the clay and the mica it contains can be broken down to make pottery, that same clay has to be used to form the entire final product. It can be coiled and scraped but that final product will always be thicker, heavier and rougher on the surface. This is the preferred micaceous clay for making utilitarian pottery and utensils. It is essentially waterproof and conducts heat evenly.

The second kind is the preferred micaceous clay for most non-functional fine art pieces. It has less of a mica content with smaller embedded pieces of mica. It is more easily broken down by the potters and more easily made into a slip to cover a base made of other clay. Even as a slip, the mica serves to bond and strengthen everything it touches. The finished product can be thinner and have a smoother surface. As a slip, it can also be used to paint over other colors of clay for added effect. However, these micaceous pots may be a bit more water resistant than other Pueblo pottery but they are not utilitarian and will not survive utilitarian use.

While all micaceous clay from the area of Taos turns golden when fired, it can also be turned black by firing in an oxygen reduction atmosphere. Black fire clouds are also a common element on golden micaceous pottery.

Mica is a relatively common component of clay, it's just not as visible in most. Potters at Hopi, Zuni and Acoma have produced mica-flecked pottery in other colors using finely powdered mica flakes. Some potters at San Ildefonso, Santa Clara, Jemez and San Juan use micaceous slips to add sparkle to their pieces.

Potters from the Jicarilla Apache Nation collect their micaceous clay closer to home in the Jemez Mountains. The makeup of that clay is different and it fires to a less golden/orange color than does Taos clay. Some clay from the Picuris area fires less golden/orange, too. Christine McHorse, a Navajo potter who married into Taos Pueblo, uses various micaceous clays on her pieces depending on what the clay asks of her in the flow of her creating.

There is nothing in the makeup of a micaceous pot that would hinder a good sgraffito artist or light carver from doing her or his thing. There are some who have learned to successfully paint on a micaceous surface. The undecorated sparkly surface in concert with the beauty of simple shapes is a real testament to the artistry of the micaceous potter.

Lonnie Vigil

Nambe

Robert Vigil

Nambe

Preston Duwyenie

Hopi

Gonzales Family Tree

Disclaimer: This "family tree" is a best effort on our part to determine who the potters are in this family and arrange them in a generational order. The general information available is questionable so we have tried to show each of these diagrams to living members of each family to get their input and approval, too. This diagram is subject to change should we get better info.

-

Ramona Sanchez Gonzales (1885-), second wife of Juan Gonzales (painter)

- Blue Corn (Crucita Gonzales Calabaza)(1921-1999)(step-daughter of Ramona) & Santiago Calabaza (Santo Domingo) (d. 1972)

- Joseph Calabaza (Tha Mo Thay)

- Diane Calabaza-Jenkins (Heishi Flower) (1955-)

- Elliot Calabaza

- Oqwa Pi (Abel Sanchez)(1899-1971) & Tomasena Cata Sanchez (1903-1985)

- Skipped generation

- Russell Sanchez (1966-)

- Skipped generation

- Rose (Cata) Gonzales (daughter-in-law) (1900-1989) & Robert Gonzales (1900-1935)

- (Johnnie) Tse-Pe (Gonzales)(1940-2000) & Dora Tse-Pe (Gachupin, first wife, Zia, 1939-2022)

- Andrea Tse Pe (1975-)

- Candace Tse-Pe (1968-)

- Gerri Tse-Pe (1963-)

- Irene Tse-Pe (1961-)

- Jennifer Tse-Pe (1960-1977)

- (Johnnie) Tse-Pe (1940-2000) & Jennifer Tse Pe (Sisneros - second wife, Santa Clara)

- (Johnnie) Tse-Pe (Gonzales)(1940-2000) & Dora Tse-Pe (Gachupin, first wife, Zia, 1939-2022)

- Rose' students:

- Juanita Gonzales (1909-1988) & Louis "Wo-Peen" Gonzales (brother of Rose Gonzales husband)(1905-1992)

- Adelphia Martinez (1935-2022)

- Lorenzo Gonzales (1922-1995)(adopted by Louis & Juanita Gonzales) & Delores Naquayoma (Hopi/Winnebago)

- Jeanne M. Gonzales (1959-)

- John Gonzales (1955-)

- Laurencita Gonzales

- Linda Gonzales

- Marie Ann Gonzales

- Raymond Gonzales

- Robert Gonzales

- Juanita Gonzales (1909-1988) & Louis "Wo-Peen" Gonzales (brother of Rose Gonzales husband)(1905-1992)

Some of the above info is drawn from Pueblo Indian Pottery, 750 Artist Biographies, by Gregory Schaaf, © 2000, Center for Indigenous Arts & Studies. Other info is derived from personal contacts with family members and through interminable searches of the Internet.

Copyright © 1998-2025 by