Click or tap to see a larger version

Robert Tenorio, Santo Domingo, Polychrome dough bowl decorated with a 4-panel horse and geometric design inside and a geometric design outside

Santo Domingo

$ 2600

zzsd1g320

Polychrome dough bowl decorated with a 4-panel horse and geometric design inside and a geometric design outside

15 in L by 15 in W by 6.75 in H

Condition: Very good

Signature: Robert Tenorio Kewa N.M.

Sale Price: $1950

Tell me more! Buy this piece!

(505) 986-1234 - www.andreafisherpottery.com - All Rights Reserved

Robert Tenorio

Santo Domingo

Born in 1950, Robert Tenorio grew up on Santo Domingo Pueblo in northern New Mexico. He began working with clay early in life, learning the basics with his grandmother Andrea Ortiz and his great-aunt Lupe Tenorio. However, when he finished high school and moved on to the Institute of American Indian Arts (IAIA) in Santa Fe he began studying art and jewelry design. Before too long he switched back and began formal training with clay under Otellie Loloma.

When he returned to the Pueblo, though, he had to learn some of the traditional art of potting all over again as he no longer had access to the clays and the kiln available to him at school. He began collecting and processing native clays and learning the traditional firing methods used by his people. Robert began creating pots, canteens and polychrome jars characteristic of the centuries old styles of his Santo Domingo ancestors.

Potting full time since 1970, Robert's work reflects his reverence for his heritage. Santo Domingo is known for its utilitarian ware decorated with birds, fish, flowers and simple geometrics, and that's what Robert says he most enjoys making.

Robert earned his first award at the Heard Museum Guild Indian Art Fair in 1971 and has won enough ribbons since to "make two quilts!" he says. One piece he entered at the Santa Fe Indian Market earned a ribbon in the new category it created: Prehistoric Pottery. In 2000 he was awarded the Governor's Award at the Santa Fe Indian Market and earned two more First Place ribbons in 2004. His work can be found in the collections of the Peabody Museum at Harvard University in Cambridge, MA, the Nagoya Museum in Japan and the Royal Family of Great Britain collection. He signs his work "Robert Tenorio, KEWA, N.M."

Some Exhibits that Featured Robert's Work

- Place, Nations, Generations, Beings: 200 Years of Indigenous North American Art. Yale University Art Gallery. New Haven, Connecticut. November 1, 2019 - June 21, 2020. Note: based on objects from the Yale University collections; accompanied by an exhibition catalogue

- Crafted to Perfection: the Nancy & Alan Cameros Collection of Southwestern Pottery. Rockwell Museum of Western Art. Corning, New York. November 22, 2007 - May 18, 2008

- Breaking the Mold: the Virginia Vogel Mattern Collection of Contemporary Native American Art. Denver Art Museum. Denver, Colorado. October 2006 - July 2007

- Home: Native People in the Southwest. Heard Museum. Phoenix, Arizona. 2005

- Hold Everything! Masterworks of Basketry and Pottery from the Heard Museum. Heard Museum. Phoenix, Arizona. November 1, 2001 - March 10, 2002

- The Seven Families of Pueblo Pottery: Simply Santa Fe. Santa Fe, New Mexico. August 16-31, 1990

- Innovators: Dorothy Torivio, Richard Zane Smith, Robert Tenorio and Karita Coffey. Gallery 10. Scottsdale, Arizona. February 6-19, 1986

- 1981 Heard Museum Guild Annual Native American Arts Show. Heard Museum. Phoenix, Arizona. November 13-18, 1981

- 1980 Heard Museum Guild Indian Arts and Crafts Exhibit. Heard Museum. Phoenix, Arizona. November 26, 1980 - December 3, 1980

- 1979 Heard Museum Guild Indian Arts and Crafts Exhibit. Heard Museum. Phoenix, Arizona. November 21, 1979 - December 3, 1979

- The Santa Fe Indian Market in Perspective. Wheelwright Museum of the American Indian. Santa Fe, New Mexico. August 1979 - September 24, 1979

- Images from the Earth. Institute of American Indian Arts. Santa Fe, New Mexico. October 6, 1978 - November 3, 1978 1977 Heard Museum Guild Indian Arts and Crafts Exhibit. Heard Museum. Phoenix, Arizona. November 25, 1977 - December 3, 1977

- The Institute of American Indian Arts Alumni Exhibition. 1973-1974 Traveling exhibition planned for the following venues: Museum of the Institute of American Arts, Santa Fe, NM, 12/17/1973-1/26/1974; Amon Carter Museum, Fort Worth, TX, 2/14-3/31/1974; New Orleans Museum of Art, New Orleans, LA, 4/27-6/10/1974; Oklahoma Art Center, Oklahoma City, OK, 7/21-9/5/1974. (12/17/1973 - 09/05/1974)

- 1973 Heard Museum Guild Indian Arts and Crafts Exhibit. Heard Museum. Phoenix, Arizona. November 24, 1973 - December 2, 1973

- 11th Annual Scottsdale National Indian Arts Exhibition. Safari Hotel Convention Center. Scottsdale, AZ. March 29, 1972 - April 2, 1972

- 1971 Heard Museum Guild Indian Arts and Crafts Exhibit. Heard Museum. Phoenix, Arizona. November 27, 1971 - December 5, 1971

- 1971 Tenth Scottsdale National Indian Arts Exhibition. Executive House. Scottsdale, Arizona. February 27, 1971 - March 7, 1971

- 1970 Heard Museum Guild Indian Arts and Crafts Exhibit. Heard Museum. Phoenix, Arizona. November 28, 1970 - December 6, 1970

- 1970 Ninth Scottsdale National Indian Arts Exhibition. Executive House. Scottsdale, Arizona. February 28, 1970 - March 8, 1970

- 1969 Heard Museum Guild Indian Arts and Crafts Exhibit. Heard Museum. Phoenix, Arizona. March 29, 1969 - April 6, 1969

Some of the Awards Robert Earned

- 2006 Heard Museum Guild Indian Fair & Market, Classification II - Pottery, Division A - Traditional - native clay/hand built/painted: Second Place

- 2004 Santa Fe Indian Market, Classification II - Pottery, Division F - Traditional pottery, painted designs on matte or semi-matte surface, all forms except jars, Category 1302 - Other bowl forms: First Place

- 2004 Santa Fe Indian Market, Classification II - Pottery, Division F - Traditional pottery, painted designs on matte or semi-matte surface, all forms except jars, Category 1305 - Plates: First Place

- 2003 Heard Museum Guild Indian Fair & Market, Classification III - Cultural items, Division A - Personal ornamentation/accessories: Honorable Mention

- 2003 Heard Museum Guild Indian Fair & Market: Judge's Choice Award - Susan Folwell. Awarded for artwork: "The Train Changes the World of Pueblo Pottery"

- 2002 Santa Fe Indian Market, Classification II - Pottery, Division E - Traditional pottery, jars (including wedding jars), painted designs on matte or semi-matte surface, Category 1204 - Jars, Santo Domingo or Cochiti: First Place

- 2002 Santa Fe Indian Market, Classification II - Pottery, Division F - Traditional pottery, painted designs on matte or semi-matte surface, Category 1301 - Seed bowls, opening must be top center: Second Place

- 2001 Santa Fe Indian Market, Classification II - Pottery, Division E - Traditional pottery jars, painted designs on matte or semi-matte surface, Category 1204 - Jars, Santo Domingo or Cochiti: Third Place

- 2000 Santa Fe Indian Market, Classification II - Pottery, Division E - Traditional pottery, jars with painted designs on matte or semi-matte surface, Category 1206 - Jars, Zia, Santa Ana, Santo Domingo or Cochiti: Third Place

- 2000 Santa Fe Indian Market, Classification II - Pottery, Division F - Traditional pottery, painted designs on matte or semi-matte surface, all forms except jars, Category 1314 - Miscellaneous: First Place

- 2000 Santa Fe Indian Market, Classification II - Pottery, Division G - Non-traditional pottery, new forms using traditional materials & techniques, Category 1405 - Bowls: First Place

- 1998 Santa Fe Indian Market, Classification II - Pottery, Division E - Traditional pottery, jars, painted designs on matte or semi-matte surface, Category 1206 - Jars, Zia, Santa Ana, Santo Domingo, Cochiti: First Place

- 1998 Santa Fe Indian Market, Classification II - Pottery, Division F - Traditional pottery, painted designs on matte or semi-matte surface, all forms except jars, Category 1304 - Other bowl forms (over 9" in diameter): Second Place

- 1997 Santa Fe Indian Market, Classification II - Pottery, Division E - Traditional pottery, jars, painted designs on matte or semi-matte surface, Category 1206 - Jars, Zia, Santa Ana, Santo Domingo, Cochiti: First Place

- 1997 Santa Fe Indian Market, Classification II - Pottery, Division F - Traditional pottery, painted designs on matte or semi-matte surface, all forms except jars, Category 1302 - Seed bowl (over 7" in diameter): Third Place

- 1996 Santa Fe Indian Market, Classification II - Pottery, Division E - Traditional pottery, jars, painted designs on matte or semi-matte surface, Category 1206 - Jars, Zia, Santa Ana, Santo Domingo, Cochiti: Second Place

- 1996 Santa Fe Indian Market, Classification II - Pottery, Division F - Traditional pottery, painted designs on matte or semi-matte surface, all forms except jars, Category 1307 - Canteens: First Place

- 1996 Santa Fe Indian Market, Classification II - Pottery, Division F - Traditional pottery, painted designs on matte or semi-matte surface, all forms except jars, Category 1314 - Miscellaneous: Third Place

- 1995 Santa Fe Indian Market, Lorenzo Gonzales Memorial Award-Excellence in San Ildefonso Polychrome

- 1995 Santa Fe Indian Market: Indian Arts Fund-Excellence in Any Traditional Art

- 1995 Santa Fe Indian Market, Classification II - Pottery, Division E - Traditional pottery, painted designs on matte or semi-matte surface, jars, Category 1305 - Jars, Zia, Santa Ana, Santo Domingo, or Cochiti: First Place

- 1995 Santa Fe Indian Market, Classification II - Pottery, Division E - Traditional pottery, painted designs on matte or semi-matte surface, jars, Category 1307 - Jars, other tribes or pueblos: Second Place

- 1995 Santa Fe Indian Market, Classification II - Pottery, Division G - Traditional pottery, painted designs on matte or semi-matte surface, all forms but jars, Category 1404 - Other bowl forms (over 9 inches in diameter): First Place

- 1995 Santa Fe Indian Market, Classification II - Pottery, Division G - Traditional pottery, painted designs on matte or semi-matte surface, all forms but jars, Category 1408 - Plates: First Place

- 1994 Santa Fe Indian Market, Classification II - Pottery, Division G - Traditional pottery, painted designs on matte or semi-matte surface, all forms but jars, Category 1404 - Other bowl forms (over 9 inches in diameter): Second Place

- 1993 Santa Fe Indian Market, Classification II - Pottery, Division F - Traditional pottery, painted designs on matte or semi-matte surface, jars: Best of Division

- 1993 Santa Fe Indian Market, Classification II - Pottery, Division F - Traditional pottery, painted designs on matte or semi-matte surface, jars, Category 1303 - Jars, Zia, Santa Ana, Santo Domingo or Cochiti: First Place

- 1993 Santa Fe Indian Market, Classification II - Pottery, Division G - Traditional pottery, painted designs on matte or semi-matte surface, all forms but jars, Category 1406 - Canteens: Second Place

- 1992 Santa Fe Indian Market, Classification II - Pottery, Division F - Traditional pottery, painted designs on matte or semi-matte surface, jars, Category 1303 - Jars, Zia, Santa Ana, Santo Domingo or Cochiti: First Place

- 1992 Santa Fe Indian Market, Classification II - Pottery, Division G - Traditional pottery, painted designs on matte or semi-matte surface, all forms but jars, Category 1404 - Other bowl forms (over 8" in diameter): First Place

- 1992 Santa Fe Indian Market, Classification II - Pottery, Division G - Traditional pottery, painted designs on matte or semi-matte surface, all forms but jars, Category 1406 - Canteens: First Place

- 1991 Santa Fe Indian Market: Large Pottery Award - Best Traditional Pottery Bowl or Jar 15 inches or more in Height or Diameter

- 1991 Santa Fe Indian Market, Classification II - Pottery, Division F - Traditional pottery, painted designs on matte or semi-matte surface, jars, Category 1303 - Jars, Zia, Santa Ana, Santo Domingo or Cochiti: First Place

- 1991 Santa Fe Indian Market, Classification II - Pottery, Division G - Traditional pottery, painted designs on matte or semi-matte surface, all forms but jars, Category 1404 - Other bowl forms (over 8" in diameter): First Place

- 1991 Santa Fe Indian Market, Classification II - Pottery, Division G - Traditional pottery, painted designs on matte or semi-matte surface, all forms but jars, Category 1406 - Canteens: Second Place

- 1990 Santa Fe Indian Market, Classification II - Pottery, Division G - Traditional pottery, painted designs on matte or semi-matte surface, all forms but jars, Category 1210 - Wedding vases: First Place

- 1990 Santa Fe Indian Market, Classification II - Pottery, Division H - Non-traditional pottery, new forms using traditional materials & techniques, Category 1307 - Miscellaneous: First Place

- 1988 Santa Fe Indian Market: Indian Arts Fund Award for Overall Excellence in any Traditional Craft

- 1988 Santa Fe Indian Market, Classification II - Pottery, Division F - Traditional pottery, painted designs on matte or semi-matte surface, Jars, Category 1203 - Jars: First Place

- 1988 Santa Fe Indian Market, Classification II - Pottery, Division F - Traditional pottery, painted designs on matte or semi-matte surface, Jars, Category 1209 - Canteens: Second Place

- 1988 Santa Fe Indian Market, Classification II - Pottery, Division F - Traditional pottery, painted designs on matte or semi-matte surface, Jars, Category 1210 - Plates: Second Place

- 1987 Gallup InterTribal Ceremonial, Classification IV - Pottery, Pots 15-18 inches: Second Place

- 1986 Santa Fe Indian Market, Classification II - Pottery, Division C - Traditional pottery, incised in the style of San Juan, Category 901 - All forms: Second Place

- 1986 Santa Fe Indian Market, Classification II - Pottery, Division F - Traditional pottery, painted designs on matte or semi-matte surface, jars, Category 1203 - Jars, Zia, Santa Ana, Santo Domingo or Cochiti: Third Place

- 1986 Santa Fe Indian Market, Classification II - Pottery, Division G - Traditional pottery, painted designs on matte or semi-matte surface, all forms but jars, Category 1207 - Other bowl forms: First Place

- 1986 Santa Fe Indian Market, Classification II - Pottery, Division G - Traditional pottery, painted designs on matte or semi-matte surface, all forms but jars, Category 1210 - Plates: Second Place

- 1984 Santa Fe Indian Market: Potcarrier Award - Best Traditional Pottery Jar or Bowl 15 inches or more in height or diameter

- 1984 Santa Fe Indian Market, Classification II - Pottery, Division F - Traditional pottery, painted designs on matte or semi-matte surface, Category 1203 - Jars, Zia, Santa Ana, Santo Domingo or Cochiti: Second Place

- 1984 Santa Fe Indian Market, Classification II - Pottery, Division F - Traditional pottery, painted designs on matte or semi-matte surface, Category 1206 - Other bowl forms: First Place

- 1983 Santa Fe Indian Market, Potcarrier Award - Best traditional jar or bowl

- 1983 Santa Fe Indian Market, Classification II - Pottery, Division F - Traditional, painted designs on matte or semi-matte surface: First Place

- 1983 Santa Fe Indian Market, Classification II - Pottery, Division F - Traditional, painted designs on matte or semi-matte surface: Second Place

- 1981 Heard Museum Guild Fourteenth Annual Native American Arts Show, Classification V - Pottery, Division A - Traditional polychrome: First Place

- 1981 Santa Fe Indian Market, Classification - Pottery: First Place

- 1981 Santa Fe Indian Market, Classification Pottery: Second Place

- 1980 Heard Museum Guild Indian Arts and Crafts Exhibit, Classification VII - Pottery, Division A - Traditional Construction and Firing: Honorable Mention

- 1980 Santa Fe Indian Market, Classification Pottery: First Place

- 1980 Santa Fe Indian Market, Classification Pottery: Second Place

- 1980 Santa Fe Indian Market: Special Judges Award

- 1979 Heard Museum Guild Indian Arts and Crafts Exhibit: Best of New Mexico Pottery

- 1979 Heard Museum Guild Indian Arts and Crafts Exhibit: Popovi Da Award for Pottery

- 1979 Heard Museum Guild Indian Arts and Crafts Exhibit: Best of Pottery

- 1979 Heard Museum Guild Indian Arts and Crafts Exhibit, Classification VII - Pottery, Division A - Traditional Methods of Construction and Firing: Third Place

- 1979 Heard Museum Guild Indian Arts and Crafts Exhibit, Classification VII - Pottery, Division A - Traditional Methods of Construction and Firing: Honorable Mention

- 1979 Heard Museum Guild Indian Arts and Crafts Exhibit, Classification VII - Pottery, Division C - Figurines and Representations: Third Place

- 1979 Santa Fe Indian Market: Special Judges Award

- 1979 Santa Fe Indian Market, Pottery - Painted (Designs on matte or semi-matte surface), Canteens: First Place

- 1977 Heard Museum Guild Indian Arts and Crafts Exhibit, Classification VII - Pottery, Division D - Kiln fired: Second Place

- 1974 Santa Fe Indian Market, Pottery - Santo Domingo Pueblo: First Place

- 1973 Heard Museum Guild Indian Arts and Crafts Exhibit, Classification XII - Pottery, Division A - Traditional shapes and designs: Honorable Mention (2)

- 1972 11th Annual Scottsdale National Indian Arts Exhibition, Section C - Crafts, Classification VIII - Pottery, Division C - Contemporary: Second Place

- 1972 11th Annual Scottsdale National Indian Arts Exhibition, Section C - Crafts, Classification VIII - Pottery, Division C - Contemporary: Third Place

- 1971 Heard Museum Guild Indian Arts and Crafts Exhibit, Classification XII - Pottery, Division B - Contemporary Pottery: Third Place

- 1971 Tenth Scottsdale National Indian Arts Exhibition, Section C - Crafts, Classification VIII - Pottery, Division C - Contemporary (wheel thrown in combination with other techniques; pinch, slap or any combination, and any method of firing): First Place

- 1971 Tenth Scottsdale National Indian Arts Exhibition, Section C - Crafts, Classification VIII - Pottery, Division C - Contemporary (wheel thrown in combination with other techniques; pinch, slap or any combination, and any method of firing): Third Place

- 1970 Heard Museum Guild Indian Arts and Crafts Exhibit, Classification XII - Pottery, Division B - Contemporary Pottery: Second Place

- 1970 Heard Museum Guild Indian Arts and Crafts Exhibit, Classification XII - Pottery, Division B - Contemporary Pottery: Third Place

- 1970 Ninth Scottsdale National Indian Arts Exhibition, Section B - Crafts, Classification VIII - Pottery, Division C - Contemporary (wheel thrown in combination with other techniques; pinch, slap or any combination, and any method of firing): Second Place

- 1970 Ninth Scottsdale National Indian Arts Exhibition, Section B - Crafts, Classification VIII - Pottery, Division C - Contemporary Wheel-thrown in combination with other techniques; pinch, slap or any combination, and any method of firing: Third Place

- 1969 Heard Museum Guild Indian Arts and Crafts Exhibit, Classification X - Pottery, Division C - Contemporary pottery: Second Place

- 1969 Heard Museum Guild Indian Arts and Crafts Exhibit, Classification X - Pottery, Division C - Contemporary pottery: Honorable Mention

Santo Domingo Pueblo

Santo Domingo Pueblo Mission Church

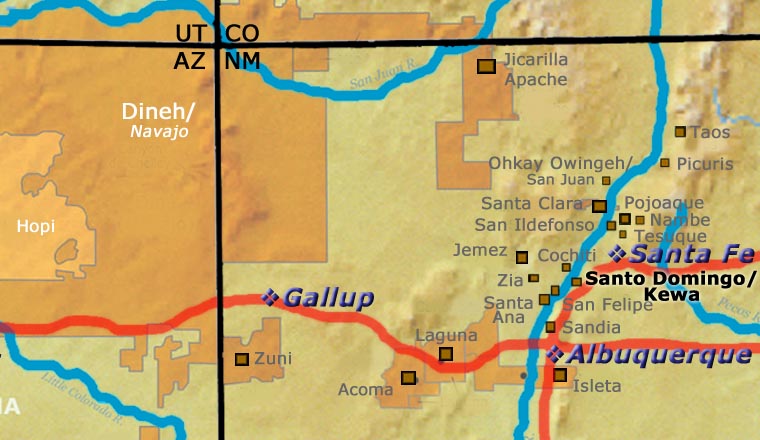

Santo Domingo Pueblo is located on the east bank of the Rio Grande about half-way between Santa Fe and Albuquerque. Historically, the people of Santo Domingo were among the most active of Pueblo traders. The pueblo also has a reputation for being ultra traditional, probably due, at least in part, to the longevity of the pueblo's pottery styles. Some of today's popular designs have changed very little since the 1700s.

In pre-Columbian times, traders from Santo Domingo were trading turquoise (from mines in the Cerrillos Hills) and hand-made heishe beads as far away as central Mexico. Many artisans in the pueblo still work in the old ways and produce wonderful silver and turquoise jewelry and heishe decorations.

Like the people of nearby San Felipe and Cochiti, the people of Santo Domingo speak Keres and trace their ancestry back to villages established on the Pajarito Plateau area in the 1400s. Like the other Rio Grande pueblos, Santo Domingo rose up against the Spanish oppressors in 1680, following Alonzo Catiti as he led the Keres-speaking pueblos and worked with Popé (of San Juan Pueblo) to stop the Spanish atrocities. However, when Spanish Governor Antonio Otermin returned to the area in 1681, he found Santo Domingo deserted and ordered it burned. The pueblo residents had fled to a nearby mountain stronghold and when Don Diego de Vargas returned to Nuevo Mexico in 1692, he attacked that mountain fortress and burned it, too. Catiti died in that battle and Keres opposition to the Spanish crumbled with his death. The survivors of that battle fled, some to Acoma, some to fledgling Laguna, some to the Hopi mesas. Over time most of them returned to Santo Domingo.

In the 1790s Santo Domingo accepted an influx of refugees from the Galisteo Basin area as they fled the near-constant attacks of Apache, Comanche, Ute and Navajo raiders in that area. Today's main Santo Domingo village was founded about 1886.

In 1598 Santo Domingo was the site of the first gathering of 38 pueblo governors by Don Juan de Oñaté to try to force them to swear allegiance to the crown of Spain. Today, the All Indian Pueblo Council (consisting of the nineteen remaining pueblo's governors and an executive staff) gathers at Santo Domingo for their first meeting every year, to continue what is now the oldest annual political gathering in America. During the time of the Spanish occupation Santo Domingo served as the headquarters of the Franciscan missionaries in New Mexico and religious trials were held there during the Spanish Inquisition.

Today, the people of Santo Domingo number around 4,500, with about two-thirds of them living on the reservation. The pottery traditions of the pueblo almost died out after the railroads arrived and many Santo Domingos went to work laying tracks. Even today many Santo Domingo men work as firefighters for the US Forest Service in fire season and practice their artistic talents during the rest of the year.

Potter Robert Tenorio began working to revive the Santo Domingo pottery tradition in the early 1970s. His influence can be found among many of today's Santo Domingo potters, even if they say he only stimulated them to learn on their own.

While today's Santo Domingo pottery is known for designs described as simple geometrics, another outstanding feature is boldness: the lines are thick and well-defined. In the 1920s, Kenneth Chapman, from the Museum of New Mexico, went to Santo Domingo and made drawings of many of the designs that were being painted on Santo Domingo pottery "before they disappeared." Thomas Tenorio said he got most of his designs from that collection.

As religious leaders forbid the representation of human figures as well as other sacred designs on pottery made for commercial purposes, birds, fish and flowers are common design motifs. Depictions of mammals are rarely seen. Another typical Santo Domingo style is to paint in the negative, meaning cover the pot in panels of big swatches of black and red so that only a few lines of the cream slip show through.

Santo Domingo Pueblo at Wikipedia

Santo Domingo Pueblo official site

Pueblos of the Rio Grande, Daniel Gibson, ISBN-13:978-1-887896-26-9, Rio Nuevo Publishers, 2001

Tenorio Family Tree

Disclaimer: This "family tree" is a best effort on our part to determine who the potters are in this family and arrange them in a generational order. The general information available is questionable so we have tried to show each of these diagrams to living members of each family to get their input and approval, too. This diagram is subject to change should we get better info.

-

Clemente & Nescita Calabaza (maternal side) & Andrea Ortiz (paternal side)

- Juanita Calabaza Tenorio (1922-1982) & Andres Tenorio

- Mary Edna Coriz (1946-) & Luciano Coriz

- Angel Bailon (1968-) & Ralph Bailon

- Paulita Pacheco (1943-2008) & Gilbert Pacheco (1940-2010)

- William Andrew Pacheco (1975-)

- Rose Pacheco (1968-) & Billy Veale (Dineh)

- Robert Tenorio (1950-)

Among Robert's students:

- Ambrose Atencio

- Corine Lovato

- Hilda Coriz (1949-2007) & Arthur Coriz (1948-1999)

- Ione Coriz (1973-)

- Warren Coriz (1966-2011)

- Mary Edna Coriz (1946-) & Luciano Coriz

-

Gilbert Pacheco's sisters who became potters:

- Laurencita Calabaza

- Santana Calabaza

- Trinidad Pacheco

- Vivian Sanchez

- Laurencita Calabaza

Some of the above info is drawn from Southern Pueblo Pottery, 2000 Artist Biographies, by Gregory Schaaf, © 2002, Center for Indigenous Arts & Studies

Other info is derived from personal contacts with family members and through interminable searches of the Internet and cross-examination of the data found.

Copyright © 1998-2025 by