Click or tap to see a larger version

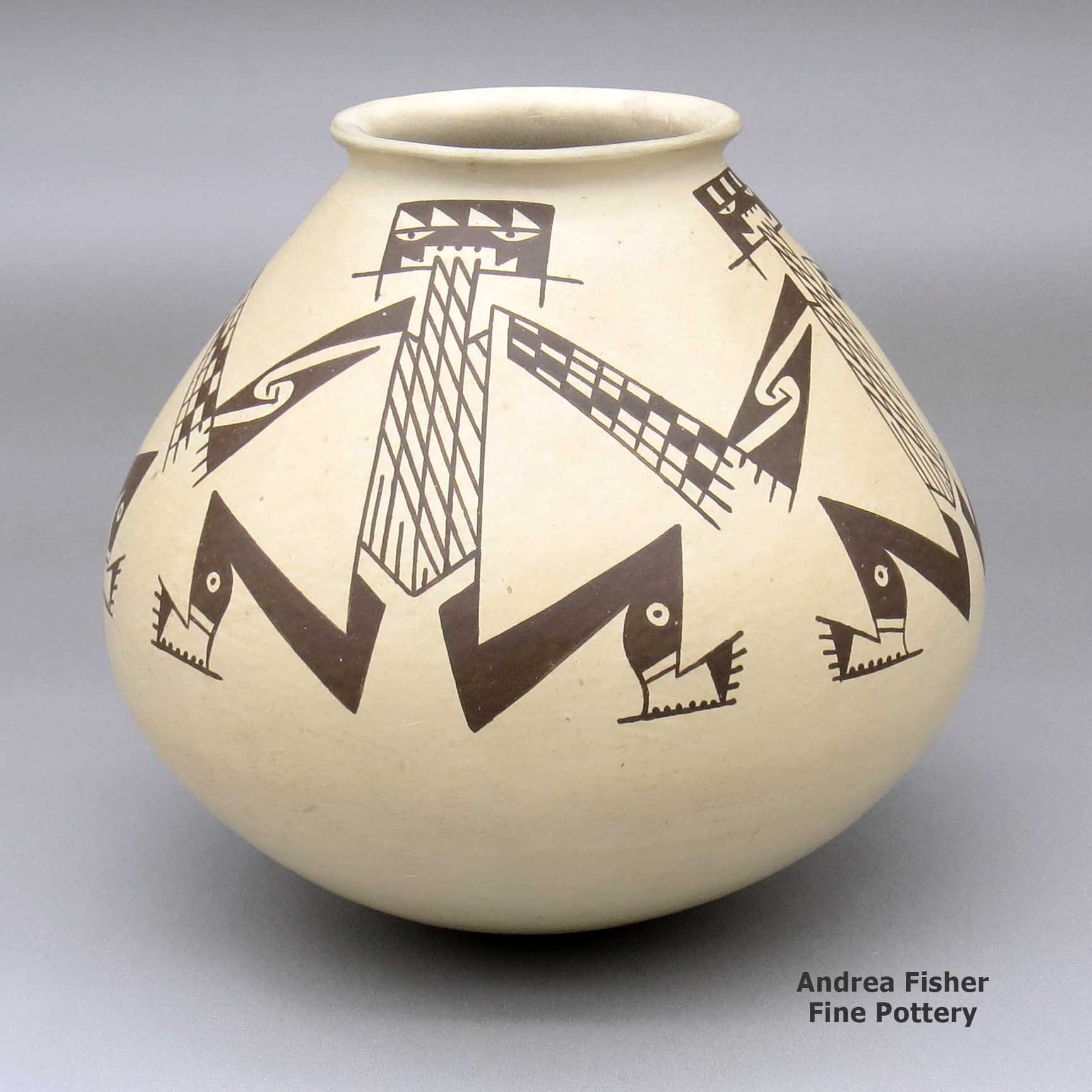

Juan Quezada Sr, Mata Ortiz and Casas Grandes, A brown-on-tan jar with a flared rim and a painted four-panel Mimbres lizard-man geometric design

Mata Ortiz and Casas Grandes

$ 1975

emcg4e176

A brown-on-tan jar with a flared rim and a painted four-panel Mimbres lizard-man geometric design

7.5 in L by 7.5 in W by 7 in H

Condition: Very good with age appropriate wear

Signature: Juan Quezada

Tell me more! Buy this piece!

(505) 986-1234 - www.andreafisherpottery.com - All Rights Reserved

Juan Quezada Sr.

1940-2022

Mata Ortiz and

Casas Grandes

Juan with Laura Bugarini

In many respects, the revival pottery of Mata Ortiz owes its birth to Juan Quezada Sr. As a young man Juan was trying to get by as a farmer, cowherd and supplier of firewood in the vicinity of the village of Mata Ortiz. Each of these activities brought him into the ruins of what were formerly outlying villages of the major pueblo of Paquimé.

By the time Spanish explorers reached the region in the early 1500s, Paquimé had been abandoned for a hundred years and was washing away more with each succeeding rainfall. However, the ruins impressed the Spanish as an example of a formerly wealthy New World community and perhaps spurred them on to find out where the gold went. These days, the ruins of Paquimé are a designated United Nations World Heritage site. Much of the area has been excavated and a significant portion of the ruins have been stabilized so that erosion doesn't have quite the effect it used to. That said, in some areas there are still ancient potsherds scattered all over the ground. To dig a few inches down is to expose many more.

There were also many unbroken pots unearthed in the area, pots showing a multitude of designs, shapes, forms and uses. Some of the designs and forms found have been traced back to the Mimbres Mogollon culture and to possible Hohokam influences. Some of the Mimbres designs are also still seen in use by Acoma, Laguna, Isleta and Zuni potters. Archaeologists have suggested that when the Mimbres Mogollan people abandoned southern New Mexico around 1150 CE, some went north to the Acoma and Laguna areas while most went south to Paquimé. The area of Paquimé may have been wetter in those days but by about 1400, it was getting pretty dry.

Juan often found himself wandering through the ruins of Paquimé, stepping on potsherds everywhere he went. Eventually he started picking them up and examining them. Then he stumbled across a cave that contained unbroken pots painted by the residents of Paquimé hundreds of years before. That led to him trying to figure out how the pots were first made, then where the colors came from and how the designs fit together. With no tools to work with outside of his own drive to discover and his own ingenuity, it took him several years to figure it out.

Juan's creations may have gone unnoticed except for the serendipitous discovery of a few of his pieces in a small shop in Deming, New Mexico by an Anglo trader named Spencer MacCallum. Spencer recognized quality when he saw it but it took him a while to follow the trail back to Juan. Once he'd met Juan, Spencer came up with a great marketing story and out of that marketing story grew the brilliance that is today's Mata Ortiz pottery. And as good a potter as Juan was, that marketing story was not a true story. It did serve to make Juan famous in the United States but in Mexico, he's almost unknown.

The meeting with Spencer MacCallum fueled Juan's rise and as his pieces brought more and more income, his siblings got more and more interested in making pottery. Before long, Juan had taught them all how to do it and over the years since, many other potters have learned, made it their own and built their own careers, making and selling pottery into the United States and global markets and bringing a level of prosperity to Mata Ortiz that the village had never known.

Juan is also the progenitor of the "Quezada style," a design style that incorporates whitespace into the overall design. In contradistinction to that is the "Porvenir style," originated by potters in the Porvenir neighborhood of Mata Ortiz. The Porvenir style essentially decorates every centimeter of a pot's surface, leaving little-to-no whitespace.

After decades of making pottery, Juan finally retired and spent his last years on a ranch atop one of the hills above Mata Ortiz. He almost stopped making pottery but he did mentor younger folks, teaching them the basics and some of his more advanced techniques. A lot of folks in Mata Ortiz owe their prosperity to Juan's willingness to teach and pass on his knowledge and techniques. The Government of Mexico honored Juan by giving him the Premio Nacional de los Artes, the highest honor Mexico gives to its finest living artists. Sadly, Juan passed away on December 1, 2022.

Mata Ortiz and Casas Grandes

The macaw pens at Paquimé

Casas Grandes is both a municipality and an archaeological district in northern Chihuahua State, Mexico. The archaeological district includes the pre-historic ruins of Paquimé, a city that began to build around 1130 AD and was abandoned about 1450 AD. Archaeologists are uncertain as to whether Paquimé was settled by migrants from the Mogollon/Mimbres settlements to the north or by Anasazi elite from the Four Corners region in the United States or by others. Over the years Paquimé was built into a massive complex with structures up to six and seven stories high with multiple Great Houses in the surrounding countryside. Today, the site is a UNESCO World Heritage Site.

Mata Ortiz is a small settlement inside the bounds of the Casas Grandes municipality very near the site of Paquimé. The fortunes of the town have gone up and down over the years with a real economic slump happening after the local railroad repair yard was relocated to Nuevo Casas Grandes in the early 1960's. The town was in steady decline until Juan Quezada, a poor farmer who gathered firewood in the area of the archaeological site, was inspired by fragments of ancient Paquimé pottery and even older fragments of Mimbres forms with bold black-on-white designs littering the ground to learn more.

Ramos Polychrome effigy pot from Paquimé

Quezada was successful in his quest to learn to recreate the ancient process using slightly more modern techniques (although no one in the present tradition uses a potter's wheel). He learned to use sand and other coarse materials for temper. He discovered that dried cow dung made an excellent and inexpensive firing fuel. Instead of using gourds for smoothing he substituted broken hacksaw blades. Instead of using yucca fiber brushes for painting he learned to make brushes with human hair. He persevered in his efforts and by 1971 had produced a kind of polychrome pottery. Since then, most pottery-making in the area has used innovations in the design and decoration of the pots but the materials and the basic crafting of the process have remained the same.

By the mid-1970s, Quezada had attracted a significant number of traders and his work was becoming a commercial success. That is when he began teaching his techniques to his immediate family. They in turn taught other family members, friends and the younger generations. Both women and men were included from the beginning.

Originally called Casas Grandes pottery in the early years of its production, the potters of this tiny village have made such an impact on the pottery communities, including many awards and special recognition from the Presidents of Mexico, that Mata Ortiz pottery is now becoming known around the world.

Today, pottery production has changed the village in many ways as there is now electricity, plumbing, vehicles and more for the residents. Virtually everyone in the small town (2010 population: 1,182) makes their living by working in some part of the pottery-making process, from potters to clay-gatherers to firewood collectors to traders.

Mata Ortiz pottery incorporates elements of contemporary and prehistoric design and decoration, and each potter or pottery family produces their own distinctive, individualized ware. Young potters from surrounding areas have been attracted to the Mata Ortiz revival and new potting families have developed while the art movement continues to expand. Without the restraints of traditional religious practices or gender constraints, a vibrant flow of new ideas has enabled the pottery of Mata Ortiz to avoid the derivative repetition common to virtually all folk art movements. This blend of economic need, gender equality, cultural expression and artistic freedom has produced a unique artistic movement in today's community.

Lower photo is courtesy of David Monniaux, Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 3.0 Unported License

Mimbres Pottery

Mimbres Mogollon Culture

Rebecca Lucario

Acoma

Verda Toledo

Jemez

Marie Z. Chino

Acoma

The Mimbres Mogollon culture was named for the Mimbres River in the Gila Mountains. They lived in the area from about 850 CE to about 1150 CE. Substantial depopulation of the area occurred but there were many small surviving populations. Over time, these melted into the surrounding cultures with many families moving north to Acoma, Zuni and Hopi while others moved south to Casas Grande and Paquimé.

The time period from about 850 CE to about 1000 CE is classed the Late Basketmaker III period. The time period was characterized by the evolution of square and rectangular pithouses with plastered floors and walls. Ceremonial structures were generally dug deep into the ground. Local forms of pottery have been classified as early Mimbres black-on-white (formerly Boldface Black-on-White), textured plainware and red-on-cream.

The Classic Mimbres phase (1000 CE to 1150 CE) was marked with the construction of larger buildings in clusters of communities around open plazas. Some constructions had up to 150 rooms. Most groupings of rooms included a ceremonial room, although smaller square or rectangular underground kivas with roof openings were also being used. Classic Mimbres settlements were located in areas with well-watered floodplains available, suitable for the growing of maize, squash and beans. The villages were limited in size by the ability of the local area to grow enough food to support the village.

Pottery produced in the Mimbres region is distinct in style and decoration. Early Mimbres black-on-white pottery was primarily decorated with bold geometric designs, although some early pieces show human and animal figures. Over time the rendering of figurative and geometric designs grew more refined, sophisticated and diverse, suggesting community prosperity and a rich ceremonial life. Classic Mimbres black-on-white pottery is also characterized by bold geometric shapes but done with refined brushwork and very fine linework. Designs may include figures of one or multiple humans, animals or other shapes, bounded by either geometric decorations or by simple rim bands. A common figure on a Mimbres pot is the turkey, another is the thunderbird. There are also a lot of different fish depicted, some are species found in the Gulf of California.

A lot of Mimbres bowls (with kill holes) have been found in archaeological excavations but most Mimbres pottery shows evidence it was actually used in day-to-day life and wasn't produced just for burial purposes.

There's a lot of speculation as to what happened to the Mimbres people as their countryside was rapidly depopulated after about 1150 CE. The people of Isleta, Acoma and Laguna find ancient Mimbres pot shards on their pueblo lands, indicating that pottery designs from the Mimbres River area migrated north. There are similar designs found on pot shards littering the ground around Casas Grandes and Paquime near Mata Ortiz and Nuevo Casas Grandes in northern Mexico. Other than where they went, the only reasons offered for why they left involve at least small scale climate change. The usual comment is "drought" but drought could have been brought on by the eruption of a volcano on the other side of the planet, or a small change in the El Nino-La Nina schedule. Whatever it was that started the outflow of people, it began in the Mimbres River area and spread outward from there. Excavations in the Eastern Mimbres region (nearer to Truth or Consequences, New Mexico) have shown that the people adapted to new circumstances and that adaptation itself moved them closer into alignment with surrounding tribes and cultures. Eventually they just kind of merged into the background, although the groups that moved south and built up Paquime and Casas Grandes seem to have lost a war and survivors migrated to the west, to a land a bit more hospitable for them.

Michael Kanteena

Laguna

Paula Estevan

Acoma

Franklin Tenorio

Santo Domingo

Juan Quezada Family and Teaching Tree

Disclaimer: This "family and teaching tree" is a best effort on our part to determine who the potters are in this grouping and arrange them in a generational order/order of influence. Complicating this for Mata Ortiz is that everyone essentially teaches everyone else (including the neighbors), so it's hard to get a real lineage of family/teaching. The general information available is scant. This diagram is subject to change as we get better info.

- Juan Quezada (1940-2022) & Guillermina Olivas Reyes (1945-)

- Nicolas Quezada & Maria Gloria Orozco

- Dora Quezada

- Elida Quezada & Ramon Lopez

- Jose Quezada (1972-) & Marisela Herrera

- Leonel Quezada Talamontes (1977-)

- Reynaldo Quezada & Monserat Treviso

- Lucia Quezada

- Lupita Quezada

- Maria de los Angeles Quezada

- Maria Guadalupe Quezada

- Mariano Quezada Treviso & Rocio de Quezada

- Fernando Andrew

- Octavio Andrew (1970-)

- Jose Cota

- Gloria Lopez

- Rosa Lopez

Rosa and Gloria's students:

- Roberto & Angela Banuelos

- Adriana Banuelos

- Diana Laura Banuelos

- Mauricio Banuelos

- Roberto & Angela Banuelos

- Lydia Quezada & Rito Talavera

- Moroni Quezada (1993-)

- Pabla Quezada

- Luly Lucero (student of Lydia) & Quico Marquez

- Jael Lucero & Victor Reyes

- Consolacion Quezada & Guadalupe Corona Sr.

- Dora Quezada

- Guadalupe Lupe Corona Jr.

- Angela Corona & Oscar Ramirez

- Jazmin Ramirez

- Gabriela Corona

- Jorge Corona

- Vidal Corona & Luz Elva Gutierrez

- Angela Corona & Oscar Ramirez

- Hilario Quezada & Matilde Olivas

- Hilario Quezada Jr.

- Mauro Corona Quezada (1968-) & Martha Martinez de Quezada

- Abelina Corona & Angel Amaya

- Jorge Amaya

- Shelyz Amaya

- Mauro Corona

- Luis Baca & Carmen Fierro

- Abelina Corona & Angel Amaya

- Oscar Corona Quezada

- Octavio Gonzales Camacho (Quezada)

- Oscar Gonzales Quezada

- Reynalda Quezada & Simon Lopez

- Samuel Lopez Quezada (1972-) & Estella S. de Lopez

- Olivia Lopez Quezada & Hector Ortega

- Yolanda Lopez Quezada

- Rosa Quezada

- Noelia Hernandez Quezada (1975-)

- Paty Quezada

- Jesus Quezada

- Imelda Quezada

- Jaime Quezada

- Jose Luis Quezada Camacho

- Mary Quezada

- Genoveva Quezada & Damian Escarcega

- Damian Quezada & Elvira Antillon

- Anjelica Escarcega

- Ana Trillo

- Adrian Corona

- Damian Escarcega

- Yesenia Escarcega

- Ivona Quezada

- Miguel Quezada

- Damian Quezada & Elvira Antillon

- Alvaro Quezada Olivas

- Arturo Quezada Olivas

- Efren Quezada Olivas

- Juan Quezada Olivas Jr. & Lourdes Luli Quintana de Quezada

- Laura Quezada

- Maria Elena Nena Quezada de Lujan

- Alondra Lujan Quezada

- Mireya Quezada

- Noe Quezada & Elizabeth Quintana

- Guillermina Quezada Quintana

- Ivan Quezada Quintana

- Lupita Quezada Quintana

- Taurina Baca (1961-)

- Gerardo Cota

- Martin Cota

- Guadalupe Lupita Cota

- Elvira Bugarini Cota & Jesus Pedregon

- Laura Bugarini Cota & Hector Gallegos Jr.

- Luz Angelica Lopez Cota

- Karla Lopez Cota

- Guadalupe Gallegos

- Ivonne Olivas

- Manuel Manolo Rodriguez Guillen (1972-)

Juan's other children who became potters:

Others who learned from Juan:

Some of the above info is drawn from:

- The Many Faces of Mata Ortiz, by Susan Lowell, © 1999, Rio Nuevo Publishers.

- Secrets of Casas Grandes: Precolumbian Art and Archaeology of Northern Mexico, edited by Melissa S. Powell, © 2006, Museum of New Mexico Press.

- Mata Ortiz Pottery Today, by Guy Berger, © 2010, Schiffer Publishing Ltd.

- Mata Ortiz Pottery: Art and Life, by Ron Goebel, © 2008, self-published.

- The Miracle of Mata Ortiz, by Walter P. Parks, © 1993, The Coulter Press.

Most other info is derived from either personal contacts with family members or with individual traders plus interminable searches of the Internet and cross-examinations of the data found.

Copyright © 1998-2025 by