Jennie Trammel

1929-2010

Santa Clara

Jennie's hallmark

Born in 1929, Jennie Trammel was the daughter of Alcario and Margaret Tafoya. In those days, all births at the pueblo were overseen by a midwife, who was usually the mother's clan mother. In Jennie's case, the midwife was her grandmother, Sara Fina Tafoya, and that turned out to be very beneficial: Jennie was stillborn. Sara Fina was a highly experienced midwife and healer. As soon as she realized Jennie's condition, she began massaging the baby's tiny chest and then "breathed life into her." 1929 was long before the concept of CPR was in vogue, and none of us can pronounce the Tewa words we heard for that.

Jennie's earliest years were spent in Sara Fina's home. Then she was sent off to be educated in government Indian schools. After that she married Charles Franklin Trammel and they moved to California for work. In California she sorted oranges while he worked for Rocketdyne, testing various rocket fuels. Rocketdyne was later merged into NASA, then into Boeing. However, Jennie and Charles returned to Santa Clara and he went to work at Los Alamos just as the Manhattan Project was turning into what is now Los Alamos National Laboratory.

Sara Fina died in 1949, near the beginning of an outbreak of smallpox on the pueblo. Jennie's son Gordon was the last child born on the pueblo with a midwife attending (1959). After that, all pueblo babies were born in an IHS hospital and that was the end of the smallpox problem at Santa Clara.

Jennie may have learned the basics of how to make pottery through watching and working with her mother and grandmother early in life but the education in government schools tried to erase that. Her own daughter, Karen, was born before she really got into making pottery herself. Then she learned from her mother, sisters and brother. By the time Charles passed on in 1967, Jennie was becoming a recognized potter in her own right.

Karen told us that her mother never told a lie. Jennie may have attributed that to the circumstances of her birth but, as she often told Karen, "True words may fade away over time but lies, they never fade away. They live forever. Never tell a lie, no matter how hard it is to tell the truth."

Jennie's work was part of the Seven Families in Pueblo Pottery exhibition at the Maxwell Museum of Anthropology of the University of New Mexico in 1974. Shortly after that she started participating in the Santa Fe Indian Market, winning a Second Place ribbon for a black wedding vase and a Third Place ribbon for a carved red jar in 1976. Then came another Third Place ribbon for a jar in 1977. But she was never a regular participant at any show, she liked to live a very private life. To that end she didn't produce very much pottery but what she did produce was very well received.

Jennie preferred to make both long and short necked, medium sized, red water jars. She never made anything very large nor very small. Her favorite designs to carve include the avanyu, kiva steps and a particular geometric design she developed to use as her hallmark. She passed on in 2010.

100 West San Francisco Street, Santa Fe, New Mexico 87501

(505) 986-1234 - www.andreafisherpottery.com - All Rights Reserved

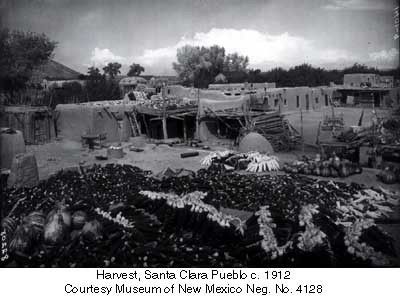

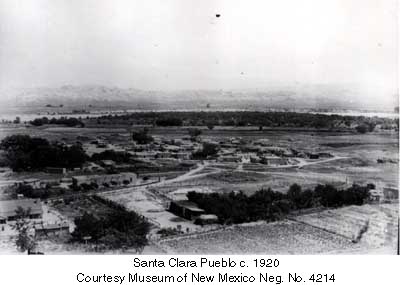

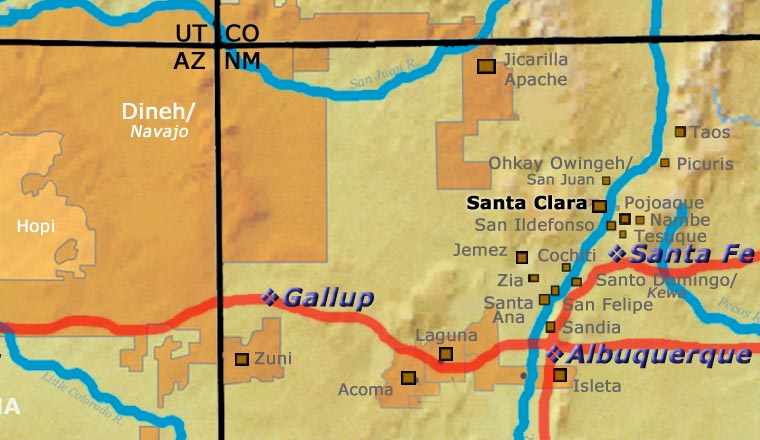

Santa Clara Pueblo

Ruins at Puye Cliffs, Santa Clara Pueblo

Santa Clara Pueblo straddles the Rio Grande about 25 miles north of Santa Fe. Of all the pueblos, Santa Clara has the largest number of potters.

The ancestral roots of the Santa Clara people have been traced to ancient pueblos in the Mesa Verde region in southwestern Colorado. When that area began to get dry between about 1100 and 1300 CE, some of the people migrated eastward, then south into the Chama River Valley where they constructed several pueblos over the years. One was Poshuouinge, built about 3 miles south of what is now Abiquiu on the edge of the Jemez foothills above the Chama River. Eventually reaching two and three stories high, and with up to 700 rooms on the ground floor, Poshuouinge was occupied from about 1375 CE to about 1475. Drought then again forced the people to move, some of them going to the area of Puye (on the eastern slopes of the Pajarito Plateau of the Jemez Mountains) and others downstream to Ohkay Owingeh (San Juan Pueblo, along the Rio Grande). Beginning around 1580 CE, drought forced the residents of the Puye area to relocate closer to the Rio Grande and they founded what we now know as Santa Clara Pueblo on the west bank of the river, with San Juan Pueblo to the north and San Ildefonso Pueblo to the south.

In 1598 the seat of Spanish government was established at Yunque, near San Juan Pueblo. The Spanish proceeded to antagonize the Puebloans so badly that that government was moved to Santa Fe in 1610, for their own safety.

Spanish colonists brought the first missionaries to Santa Clara in 1598. Among the many things they forced on the people, those missionaries forced the construction of the first mission church around 1622. However, like the other pueblos, the Santa Clarans chafed under the weight of Spanish rule. As a result, they were in the forefront of the Pueblo Revolt of 1680. One Santa Clara resident, a mixed black and Tewa man named Domingo Naranjo, was one of the rebellion's ringleaders. However, the pueblo unity that allowed them to chase the Spanish out fell apart shortly after their success, especially after Popé died.

When Don Diego de Vargas came back to the area in 1694, he found most of the Santa Clarans on top of nearby Black Mesa (with the people of San Ildefonso). A six-month siege didn't subdue them so finally, the two sides negotiated a treaty and the people returned to their pueblos. However, successive invasions and occupations by northern Europeans took their toll on all the tribes over the next 250 years. Then the swine flu pandemic in 1918 almost wiped them out.

Today, Santa Clara Pueblo is home to as many as 2,600 people and they comprise probably the largest per capita number of artists of any North American tribe (estimates of the number of potters run as high as 1-in-4 residents).

Today's pottery from Santa Clara is typically either black or red. It is usually highly polished and designs might be deeply carved or etched ("sgraffito") into the pot's surface. The water serpent, (avanyu), is a very common traditional design motif on Santa Clara pottery. Another motif comes from the legend that a bear helped the people find water during a drought. The bear paw has appeared on much of their pottery ever since.

Santa Clara has received a lot of distinction because of the evolving artistry the potters have brought to their craft. Not only did this pueblo produce excellent black and redware, several notable innovations helped move pottery from the realm of utilitarian vessels into the domain of art. Different styles of polychrome redware emerged in the 1920s-1930s. In the early 1960s experiments with stone inlay, incising and double firing began. Modern potters have also extended the tradition with unusual shapes, slips and designs, illustrating what one Santa Clara potter said: "At Santa Clara, being non-traditional is the tradition." (This refers strictly to artistic expression; the method of creating pottery remains traditional).

Santa Clara Pueblo is home to a number of famous pottery families: Tafoya, Baca, Gutierrez, Naranjo, Suazo, Chavarria, Garcia, Vigil, and Tapia - to name a few.

100 West San Francisco Street, Santa Fe, New Mexico 87501

(505) 986-1234 - www.andreafisherpottery.com - All Rights Reserved